The Drugless Cure: Chiropractors, Flu and the Law

By Tina Kirkham

When the flu took hold in Utah, in the autumn of 1918, there was no effective treatment. Among the folk remedies recommended in Utah's newspapers were sunshine, rum, sulphur, mint, onions, benzoin, sage tea, lemonade, cayenne pepper, turpentine fumes, and "Wizard Oil." Even Utah's medical doctors were approving controlled doses of liquor as a palliative for flu patients.

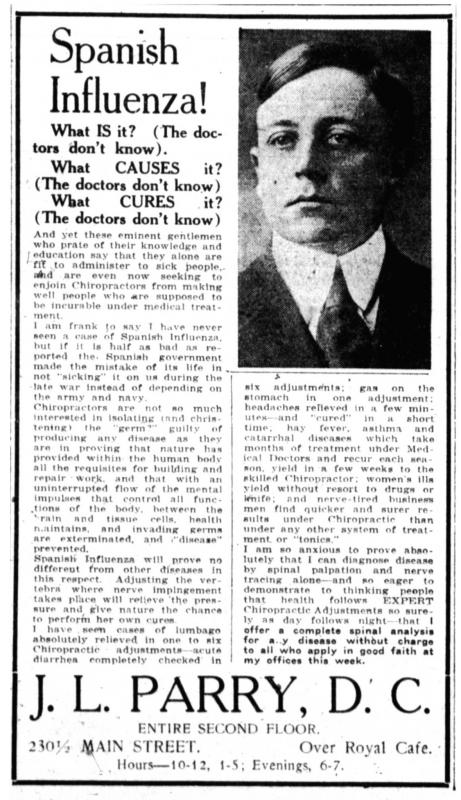

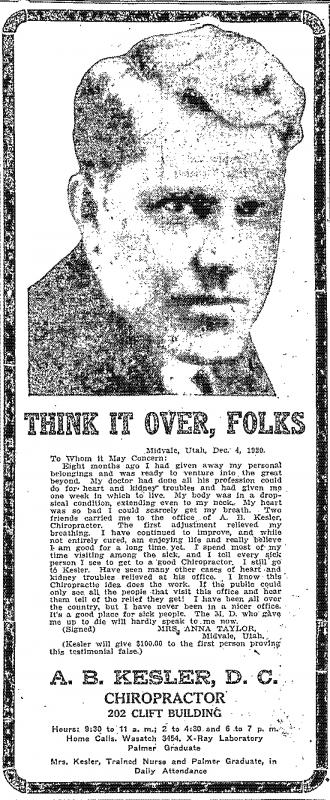

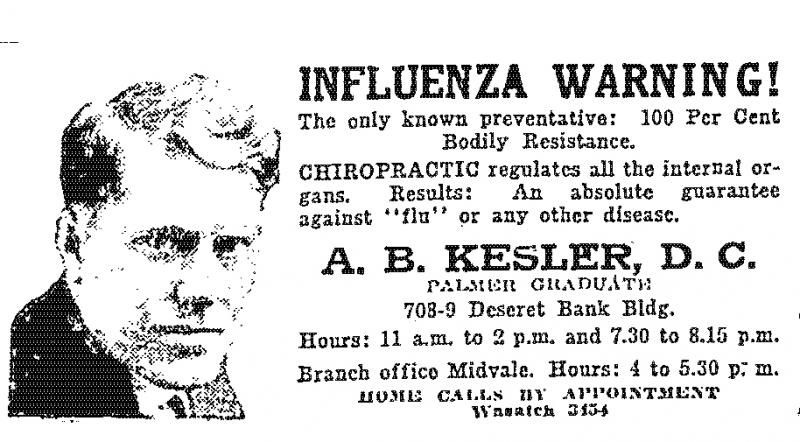

One of the first chiropractor ads claiming efficacy against the flu appeared in the Salt Lake Telegram on October 7, 1918, where chiropractor Dr. J. L. Parry stated: "Spanish Influenza! What causes it? The doctors don't know."

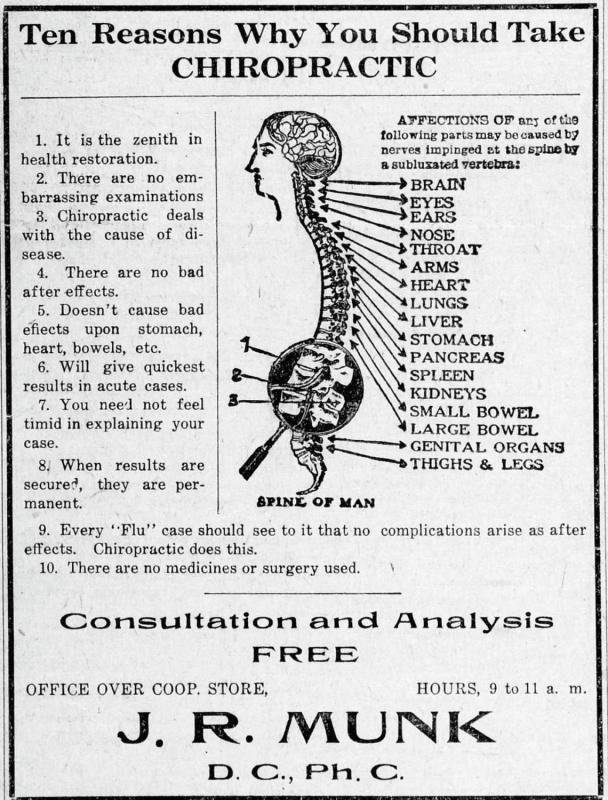

Because they believed the cause of all infirmities originated in the spine, chiropractors felt justified in claiming that they could resolve a range of ailments, including rheumatism, diabetes, appendicitis, "female troubles," and cancer. Chiropractic's founder, D. D. Palmer, described the body as a "machine" whose parts can be manipulated to produce "a drugless cure."

Chiropractic ("by hand") had emerged in the 1890s as a reaction against the "Wild West" of unregulated patent-medicine "cures." It was part of a larger shift in the public's attitude, away from powerful prescription drugs (which at the time included arsenic and opium) and dangerous invasive surgeries. The late 19th century saw a resurgence of holistic approaches to healing, in which the body is viewed as an integrated system. Traditional medical practice, they argued, treated only symptoms (pain, for example), leaving the root causes of illness untouched.

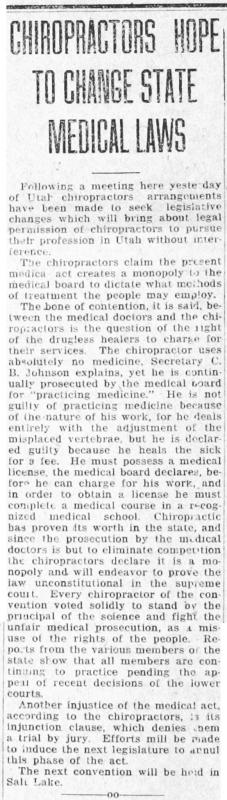

Practitioners of chiropractic were known in Utah as early as 1904, but many abandoned their practices due to the constant threat of legal action by the Board of Medical Examiners. Starting in 1911, Utah chiropractors advocated for the legalization of their art. Year after year, they tried and failed to win sufficient support at the State Capitol. The profession grew and spread across Utah, though whether its practitioners might end up in jail varied from one county to the next.

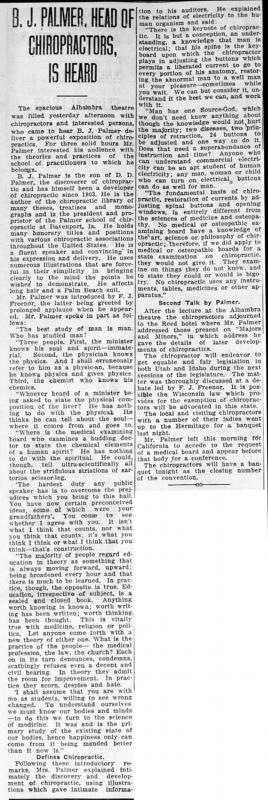

The Utah Chiropractic Association was organized, and in July 1916, a crowd of 600 gathered in Ogden to hear B. J. Palmer (D. D. Palmer's son and successor) speak. In 1914, the Association's leader, Frank Freenor, was arrested in Ogden and found guilty in a celebrated trial that had his supporters crowding the streets. Realizing that he could not be prosecuted unless he accepted payment for his services, Freenor devised a scheme in which he sold miniscule plots of land to his patients in exchange for the cost of their treatment. The following year, he was arrested a second time, and this time, he left the state. (In 1920, he would be convicted of practicing medicine without a license in San Francisco.)

Between 1915 and 1920, at least six Utah chiropractors were arrested for practicing medicine without a license. In October 1916, 25-year-old Palmer-trained chiropractor Benjamin R. Johnson was jailed in Sanpete County. Although a $100 fine would have bought his freedom, Johnson chose imprisonment in order to make a point: Utah's chiropractors were being persecuted. After he'd served nearly two-thirds of his sentence, unbeknownst to Johnson, one of his patients paid the fine and forced his release. Afterward, Johnson would describe himself in advertisements as "The man with a principle."

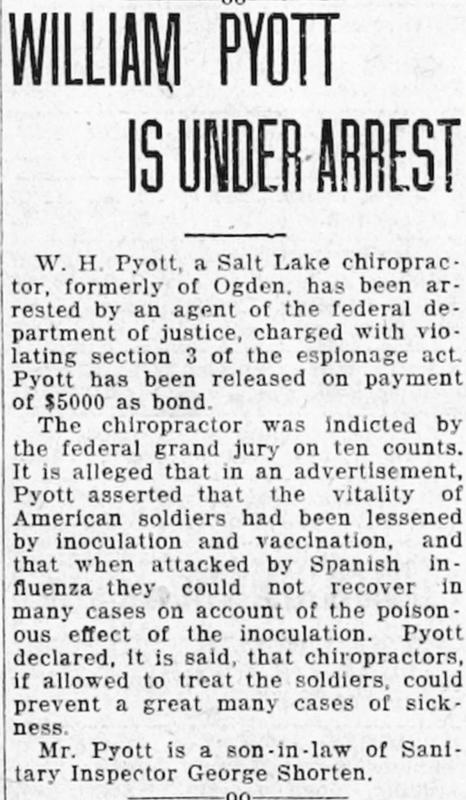

In October 1918, chiropractor Wilford H. Pyott was indicted by a grand jury on ten counts of espionage for asserting that U.S. soldiers fighting abroad had been weakened by the inoculations forced upon them when they joined the military. (The charges were dismissed in early December.) After the war and the pandemic were over, the battle between Utah's medical establishment and chiropractors only accelerated. On July 27, 1920, chiropractor O. F. Waldram published an ad that read:

Say Doctor, if you will permit me to control my carcass, while I am its tenant, and stop running around advocating selfish laws to permit you to puncture me or pump my inners full of filth or cut me up whenever you wish, you can have it to do with as you damn please when I move out.

The chiropractors pursued their cause tirelessly and strategically, calling on satisfied patients to speak on their behalf in the public debate. Historian Noble Warrum, writing in 1919, claimed that, in order to prove their integrity and good intentions, during the war some Utah chiropractors had offered their services at no charge.

In March 1923 the Utah State Legislature finally passed S.B. No. 100, although not without another eleventh-hour drama: Would the chiropractic licensing board have to include 1-2 Doctors of Medicine? The chiropractors said no, and the bill nearly died over this controversy. Senator Harrison Jenkins pointed out that any bill legalizing the profession had to include a provision for licensing, commenting:

We haven't any licensed chiropractors and never will have until we have a board and how can we have a board of the kind prescribed until we have licensed chiropractors?

The first licensing exam was held in Salt Lake City in September 1923. Of 41 applicants, 38 passed, including Benjamin Johnson and Wilford Pyott.