Brooks, Alex James

Biography

Alex James Brooks was just over one year old when the US Civil War began and five years old when it ended.[1] His early childhood was no doubt dominated by the ramifications of that war on his parents and siblings, even if he likely did not understand its significance at the time. He would grow to adulthood in southwestern Georgia during federal Reconstruction when southern Black people enjoyed some of the rights promised in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the Constitution, including citizenship and Black male voting rights. However, Brooks also lived through the rapid erosion of those rights as Reconstruction ended and federal troops were withdrawn from the South. Southern white people reasserted white supremacy through intimidation, violence, and Jim Crow laws.[2] In 1900, at the height of racial segregation in the United States, Brooks joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Meigs, Georgia, a small town of 616 people at the time, the majority of whom were Black.[3]

Brooks was born in January 1860, in Albany, Georgia, the county seat of Dougherty County, in the southwestern corner of the state. It was a region dominated by cotton plantation agriculture and formed a portion of the “Black Belt,” an interstate region of the South so named for its dark, fertile soil. The census that year counted only 3,500 free Black people in the entire state of Georgia and over 460,000 enslaved Black people.[4] Given such circumstances, it is likely that Brooks was born into slavery and born to enslaved parents.

Little is known about Brooks’s childhood or upbringing. On his baptismal record, he named Jodie Roberts as his mother and John Brooks as his father. By the 1870 census, the first time that formerly enslaved people were enumerated by name, Alex is listed along with his father and younger brother. However, the census record does not include a mother. It is possible that Alex’s mother died, was sold to another enslaver during the Civil War, or was separated from his father by the time Alex turned ten. In any case, he and his father both worked as farm laborers that year, likely in cotton production, perhaps as sharecroppers on former plantation land. They had moved one county south of Dougherty, to Mitchell County, where they eked out a living for themselves. Neither Alex nor his father could read or write.[5]

By 1880, Alex had set out on his own but still lived in Mitchell County. He worked as a farm laborer but now lived as a boarder with three brothers by the last name of Moonk, all of whom were also farm laborers. Another boarder lived with the young men and worked as a brick mason. The oldest of the five men was twenty-seven and the youngest was seventeen. Alex listed his age as nineteen. The five men lived together in Pelham, Georgia, a small agricultural village located at the southern end of Mitchell County, known for its cotton production and pecan farms. Pelham was just over five miles from Meigs, where Alex would be baptized twenty years later.[6]

Georgia tax records reveal how slow the pace of economic progress could be for freed people in Alex’s context. Three entries list Alex in Mitchell County between 1883 and 1887 and describe his property in the form of furniture, household items, and livestock. One values his property at five dollars while a later entry lists it at thirty-five. The last entry does not assign any value to his property.[7] It is a clear indication of the economic challenges that freed people faced in the postbellum South.

In that same period, between the 1880 and 1900 censuses, Alex met and married a woman named Beadie. By 1900 they had been married for fifteen years, and Beadie had given birth to seven children, six of whom were still living. Alex rented his farm, likely in a sharecropping arrangement, and still could not read or write. The farm was located in an unincorporated area of Mitchell County known as the “Maples District.”[8]

The farm that Alex rented was likely close to Meigs, and therefore the location that Latter-day Saint missionaries listed on his baptismal record as the nearest post office. Meigs is a small town that straddles the boundary between Thomas and Mitchell counties, with a portion of the town spilling over into Mitchell County. Both counties are south of Dougherty County, where Brooks was born. The population of Meigs has long hovered around one thousand people and is predominantly Black. The Brooks family likely traveled there for goods and services that they were unable to produce on their farm.[9]

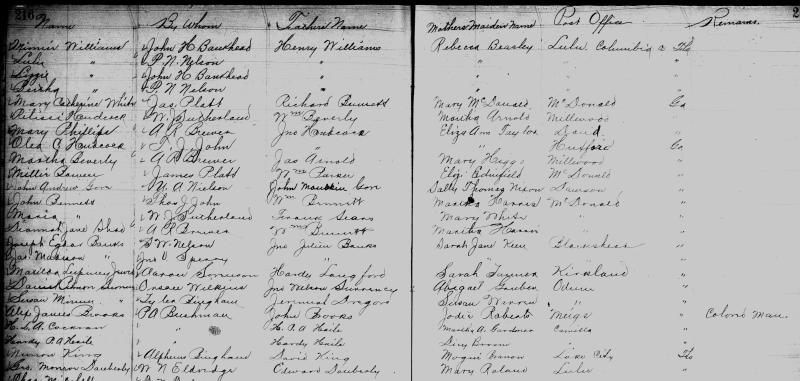

It is not clear what may have attracted Alex to the Latter-day Saint message or how he met the missionaries in the first place. In any case, Preston Ammaron Bushman from St. Joseph, Arizona, baptized and confirmed him on 1 November 1900. He was forty years old at the time. The missionary who entered his baptism into a Latter-day Saint ledger book scrawled the words “colored man” in the remarks column of the ledger. This designation set Alex apart from the other names listed in the membership record, an indication that white was deemed normal and Black was noteworthy.[10] There are no surviving sources to indicate what Alex’s religious life might have consisted of after that. There is no evidence that any of his family members followed him into his new faith. If he continued to worship as a Latter-day Saint, he might have welcomed Ann Clark, a Black woman from Meigs, into the Church in 1903 when she received baptism.[11]

By 1910, the Brooks children had all left home and Alex and Beadie lived on their farm by themselves. A second child of theirs had passed away, though it is unclear which one.[12] Their youngest child, Essie, was fourteen at the time but is not listed with them in the census. She does, however, appear on Alex’s death certificate as the informant.[13] She could have been helping the family financially by that point, working outside the home along with her seventeen-year-old brother Robert, assuming that Robert was not the child who had passed away. The 1910 census indicates that Alex had learned to read and write, even though the 1930 census again lists him as illiterate.[14] The 1910 entry could be a census error, but it is possible that Alex had spent time learning to read, perhaps using Latter-day Saint scriptures such as the Book of Mormon as a tool, possibly with the help of missionaries. He no doubt had more pressing economic matters that likely limited his practice, which could account for the return to a sense of illiteracy by 1930.

In 1930, Alex and Beadie still lived on a rented farm in southern Mitchell County but owned their home, valued at $800, an indication that the long years of hard work did yield some reward. A daughter, son-in-law, and two granddaughters lived with them at the time, likely seeking their own refuge from the difficulties of the Great Depression. The economic depression of the time is certain to have affected the Brooks, as it was particularly hard for Georgia farmers. It especially hit hard those working in cotton. On top of the economic depression, cotton farmers dealt with a boll weevil infestation which devastated crops and pricing.[15] It is fair to assume that Alex’s experience would have matched that of other Black farmers who were already vulnerable to economic hardship as they transitioned from the abolition of slavery to sharecropping.

Alex died in 1938 in Pelham, in southern Mitchell County, the same area where he had lived for the majority of his life. His death left Beadie to deal with the ramifications of the Great Depression as a widow. She appears on the 1940 census living in apparent poverty, only having made fifteen dollars in wages in 1939. She did continue to own the house that she and Alex had shared in their later years, still valued at $800. Old age is listed as a factor in Alex’s death; he was seventy-eight years old when he passed away. Essie, Alex’s youngest daughter, served as the informant for the death certificate, despite living over five hundred miles away in Philadelphia, Virginia. She also appears to have misidentified Alex’s father, whom she probably never met, and his mother, whom Alex himself seems to have been separated from early in life likely due to enslavement. His death certificate also indicates the limited access to medical care that Alex faced. It lists his cause of death as “Don’t know, had no doctor.”[16]

By Drew Holley

[1] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, images 185 and 363, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] Eric Foner, A Short History of Reconstruction, 1863-1877 (New York: Harper Perennial, 1990).

[3]Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, images 185 and 363, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah; United States, 1900 Census, Georgia, Thomas County, Meigs.

[4] “Interpreting Data: Georgia’s Enslaved Population,” Georgia Public Broadcasting, gpb.org.

[5] United States, 1870 Census, Georgia, Mitchell County.

[6] United States, 1880 Census, Georgia, Mitchell County, Pelham.

[7] Georgia, Property Tax Digests, 1883-1887, Mitchell County, Georgia Archives, Marrow, Georgia.

[8] United States, 1900 Census, Georgia, Mitchell County, Maples Precinct.

[9] United States, 1900 Census, Georgia, Thomas County, Meigs.

[10] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, images 185 and 363, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[11] Julia Huddleston, “Ann Clark,” Century of Black Mormons.

[12] United States, 1910 Census, Georgia, Mitchell County, Militia District 1194.

[13] Georgia, Department of Public Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, File No. 318, Registered No. 26426, Alex Brooks, Georgia Archives, Marrow, Georgia.

[14] United States, 1900 Census, Georgia, Mitchell County, Maples Precinct; United States, 1930 Census, Georgia, Mitchell County, Pelham.

[15] Jamil S. Zaindalin, “Great Depression,” New Georgia Encyclopedia, georgiaencylopedia.org

[16] Georgia, Department of Public Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, File No. 318, Registered No. 26426, Alex Brooks, Georgia Archives, Marrow, Georgia.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.