Brower, Mary Ann Valentine

Biography

Mary Ann Valentine Brower was born in rural southern Virginia and then lived her entire life just across the North Carolina border in Surry County, a region typified by rolling hills. She did not know how to read or write, so she left no records of her own behind. However, her life can be pieced together through context and the encounters she had with census takers and missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. These demonstrate a life filled with struggle but also one surrounded by family and marked by resilience and hope.

Mary Ann Valentine, known as Ann or Anny was born free in 1824 in Virginia to Elizabeth (Betsy) Valentine and a father she likely did not know. Ann and her mother lived with her grandparents, Buckner and Lucinda (Cinna) Chavis Valentine. Records indicate that the Chavis and Valentine families had been free since at least the 1700s.[1]

By the time Ann was six years old her family had moved to the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains in Mount Airy, Surry County, North Carolina.[2] As cash-crop plantations took hold of the Southern economy, the South became increasingly dependent on slave labor. Free Black people often moved to less settled areas to escape the increasing legal and social constrictions they experienced as slave society hardened racial prejudices and regulated the lives of Black people. Mount Airy itself had previously been a plantation. However, many of the earliest settlers of Surry County were Quakers who opposed slavery, perhaps making it a more attractive place for free Black people to settle.[3]

The Valentine family were farmers when they moved with Ann to Surry County. There they eked out a difficult existence on land so hilly it was almost unsuitable for cultivation.[4] No matter their race, farmers and their families toiled through every hour of daylight. Ann likely grew up helping her grandmother Cinna and mother Betsy cook their food over a fire. Women generally maintained the home garden that fed their families as well as spun thread, wove cloth, and sewed their own clothes. Washing those clothes was a day long chore, using soap they had made themselves. Women also frequently attended to childbirth and took care of each other using knowledge that had been passed down through generations.[5]

In addition to the challenges of daily life, Black farmers faced extra pressures. They often had to defend their land ownership. Enslavement and indenture were an ever-present threat, not only for themselves, but for their children. It could be imposed on them if they went into debt, did not meet legal requirements, or through abduction by ruthless slave traders.[6] The Valentines knew this threat. Ann’s great-grandmother Sarah had been “bound out” as a young girl, though not permanently.[7] And in 1807, a Nancy Valentine, also of North Carolina but not a known relative of Ann’s, advertised in a paper that her three freeborn daughters had been kidnapped by slavers.[8]

Ann’s grandfather, Buckner, died sometime between 1830 and 1840 and her grandmother Cinna became blind, leaving her mother Betsy to take care of the family.[9] The 1850 census taker found Ann that year still living with her mother and grandmother in Surry County. Whether the family stayed on the same land that Ann’s grandfather had farmed is not clear but they were probably no longer farming by then. The census describes Ann’s sixteen year old uncle, Chesley, as a laborer, who also lived in the household. The census taker did not record an occupation for any of the women in the family, an example of the erasure of women’s work prevalent in such records.[10]

In 1850, there were also two boys in the household, William, age seven and Henry who was four. William and Henry do not appear in any other census records and the 1850 census does not indicate how or if they were related to other members of the household. In 1900, Ann or a relative told the census taker that she had given birth to two children and both had died. Whether these two children were William and Henry, it is impossible to know. In any case, it is clear that at some point in her life Ann suffered the loss of her only two biological children.[11]

Even though the circumstances are unclear, surviving records indicate that Ann nonetheless became a mother to many other children. Four years after the Civil War, on January 6, 1869, when she was about 45 years old, Ann married Thomas Nelson Brower (known as Nelson) who was likely formerly enslaved.[12] In the 1870 census, the newly married couple had five children living with them, ranging in age from 5 to 15 years old. It is possible that Nelson brought the children with him into the marriage or perhaps Ann and Nelson took in children orphaned by slavery and the Civil War, or maybe both. In any case, the Brower family that Ann now created with Nelson, like the Valentine family she had grown up in, were farmers, scraping out an existence on rocky soil.[13] Though still mortgaged, the Browers owned their own land in 1870.

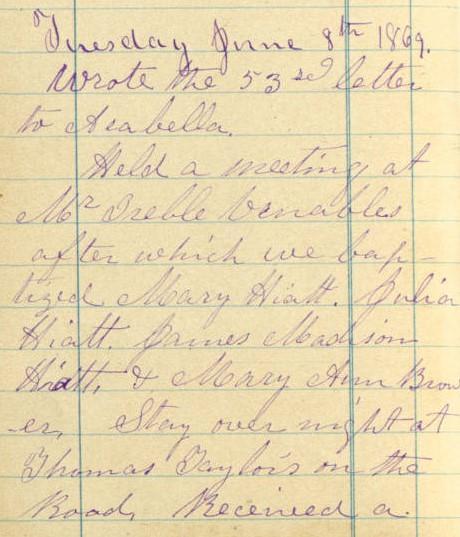

At the same time that Ann’s life changed so dramatically through marriage and family, she also sought a closer relationship with God. Just a few months after she married Nelson, Ann joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Henry Boyle, a Latter-day Saint missionary from Payson, Utah, recorded her baptism in his journal on June 8, 1869. On the same day, Boyle baptized Mary Taylor Hiatt, her son James Madison Hiatt, and her mother-in-law, Julia Hiatt.[14] The Hiatts were a prominent family among the Quakers of Surry County and were opposed to slavery. Their son Edmund remembered hiding men during the Civil War who did not want to fight in the Confederate army.[15]

By the end of 1869, the missionary Henry Boyle led many of his new converts west to Utah but Ann and Mary stayed behind. Both women would have had to leave their husbands and families in order to migrate with the Latter-day Saints. Some of Mary’s children had been baptized but there is no evidence that her husband William joined. Ann, in contrast, is the only known member of her family to convert.[16]

It is not clear what type of church organizational structure Boyle left behind following his departure to Utah or how Mary and Ann might have nourished their faith along with the other new converts who did not move west. Even still, evidence does suggest that Ann continued participation in her new faith at least up through the 1890s and perhaps beyond.[17]

Documents hint at a friendship between Ann and Mary which may have sustained both women in their faith. Census records do not indicate that the two women were neighbors but they did live within the same enumeration district. Henry Boyle baptized them on the same day at the same baptismal service, an indication that they at least met each other on that occasion, if not before. After Henry Boyle’s departure in 1869, Latter-day Saint missionaries did not return to the region until the 1880s. In later membership records dating to about 1895, Ann’s full name, Mary Ann Brower, appears right under Mary Taylor Hiatt’s name with “1869” entered as the year of their baptisms and “Boyle and Coria” as the missionaries who performed the rituals (Boyle’s companion was actually Howard Knowlton Coray). Whoever created the record also scrawled the word “colored” next to Ann’s name.[18]

It is not difficult to imagine the new missionaries who returned to the region attempting to document the names of existing members. The fact that Mary and Ann appear in the new membership list indicates an ongoing affiliation with the faith and a renewed connection to the missionaries who returned to the region. In the resulting record, Mary and Ann could not recall the exact date of their baptisms but they did remember the year and the names of the missionaries who taught and baptized them.[19]

Whatever religious life Ann created for herself, family remained close. As the century turned over and old age set in, Ann and Nelson lived next to their daughter, Susan, and her husband, Jim Smith in Surry County. Another son, Frank Brower, lived nearby. Whether the preceding years had been peaceful or not, they soon brought much loss for Ann. In 1903, Susan died during childbirth and then Nelson died just one year later. His son-in-law Jim Smith and son Frank took care of funeral arrangements for their father which must have relieved Ann of that burden. Ann’s granddaughter, Celia died in 1910, six years later.[20]

Moody Funeral Home, a local mortuary, preserved death records for Ann’s family and for other African Americans who died in the area. These records spanned a ten-year period between 1903 and 1913, and included the religion of the deceased as well as the name of the clergy who officiated at the services. Methodists, for example, buried Nelson even though he did not claim a religious affiliation. Ann and Nelson’s daughter Susan was listed as a Methodist in her record but frustratingly, Ann does not appear in the available transcription of the funeral home’s list. She also does not appear in census records after 1900 which means she likely died between Nelson’s death in 1904 and the 1910 census.[21] It is possible that Ann was buried by her Latter-day Saint friends in a family cemetery or elsewhere, putting her outside the records of Moody Funeral Home.

No matter the circumstances of her death and burial, Ann left a legacy of hard work, love, and hope behind. She was surrounded by a multi-generational family her entire life, which no doubt offered her a sense of belonging. Surviving records provide only a glimpse into the conditions that a free Black woman on the northern border of North Carolina faced in the last half of the nineteenth century. Her unlikely conversion to Mormonism adds a twist all its own.

By Ami Chopine

Primary Sources

Boyle, Henry Green. Diary. Vol. 07, 1869-1870. MSS 156. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Harold B. Lee Library. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah.

Cactus Hill Cemetery and Other Cemeteries: A List of African-American Deaths and Burials From 1903 to 1913 According to the records At Moody Funeral Home. Compiled by Martha Rowe Vaughn. Surry County Digital Heritage. 2004.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. North Carolina State (Part 2). CR 375 8. Box 4727, folder 1, image 115. Church History Library. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Hiatt, Edmund Franklin. “Autobiography of Edmund Franklin Hiatt.” Hiatt-Hiett genealogy and family history, 1699-1949; being, in particular, a record of John Hiett, Quaker, England to Pennsylvania 1699. Compiled and edited by William Perry Johnson. The Jesse Hiatt Family Association: Payson, Utah. 1951.

“Lunenburg County, Virginia, 1814, Free Negroes and Mulattos.” Transcribed by William L. Bird III. Magazine of Virginia Genealogy. Vol. 33. No. 4. Fall 1995.

North Carolina. Surry County. Marriage Records, 1741-2011. Thomas Nelson Brower and Anny Valentine. January 5, 1869.

“Stolen from the Subscriber.” The Raleigh Minerva (Raleigh, North Carolina). August 27, 1807, 2.

United States. 1830 Census. North Carolina, Surry County.

United States. 1840 Census. North Carolina, Surry County.

United States. 1850 Census. North Carolina, Surry County, North Division Hollow Springs.

United States. 1860 Census. Slave Schedules. North Carolina, Surry County.

Entry for Jacob W. Brower.

United States. 1870 Census. North Carolina, Surry County, Mount Airy.

United States. 1880 Census. North Carolina, Surry County, Mount Airy.

United States. 1900 Census. North Carolina, Surry County, Mount Airy.

United States. 1910 Census, North Carolina, Surry County, Mount Airy.

Secondary Sources

Heinegg, Paul. Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware.

Humphries, Ashley Ellen. “The Migration of Westfield Quakers from Surry County, North Carolina 1786-1828.” NC Digital Online Collection of Knowledge and Scholarship. 2013.

[1] Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of North Carolina and Virginia (n.p., 2020), Chavis Family and Tann Family. There is evidence that the Chavis family were free in Virginia before 1650. Buckner’s grandmother, Lucy, received a certificate proving her freedom in 1751 in Lunenburg, Virginia.

[2] United States, 1830 Census, North Carolina, Surry County.

[3] Ashley Ellen Humphries, “The Migration of Westfield Quakers from Surry County, North Carolina 1786-1828,” NC Digital Online Collection of Knowledge and Scholarship, 2013.

[4] Buckner is listed as a planter in “Lunenburg County, Virginia, 1814, Free Negroes and Mulattos,” transcribed by William L. Bird III, Magazine of Virginia Genealogy, vol. 33, no. 4, Fall 1995, 266. Censuses before 1850 did not record occupation, but the location of the family suggests farming.

[5] Edmund Franklin Hiatt, “Autobiography of Edmund Franklin Hiatt,” Hiatt-Hiett genealogy and family history, 1699-1949; being, in particular, a record of John Hiett, Quaker, England to Pennsylvania 1699, compiled and edited by William Perry Johnson (Payson, Utah: The Jesse Hiatt Family Association, 1951).

[6] Ira Berlin, “Forward,” in Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans of Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Maryland and Delaware.

[7] Paul Heinegg, Free African Americans, Tann Family, and Valentine Family.

[8] “Stolen from the Subscriber,” The Raleigh Minerva (Raleigh, North Carolina), August 27, 1807, 2.

[9] United States, 1830 Census, North Carolina, Surry County; United States, 1840 Census, North Carolina, Surry County; United States, 1850 Census, North Carolina, Surry County, Hollow Springs North Division.

[10] United States, 1850 Census, North Carolina, Surry County, Hollow Springs North Division.

[11] United States, 1850 Census, North Carolina, Surry County, Hollow Springs North Division; United States, 1900 Census, North Carolina, Surry County, Mount Airy.

[12] Though older than Ann, Nelson does not show up in records until after the Civil War. However, one Jacob W Brower enslaved seven people, including a man who is approximately the same age as Nelson. (See United States, 1860 Census, Slave Schedules, North Carolina, Surry County, Entry for Jacob W. Brower.) In the marriage certificate, Nelson’s parents, Friday and Phebe had no last name, while the clerk recorded Ann’s mother as Betsy Valentine. (See North Carolina, Surry, Marriage Records, 1741-2011, Thomas Nelson Brower and Anny Valentine, January 5, 1869.)

[13] United States, 1870 Census, North Carolina, Surry, Mount Airy.

[14] Henry Green Boyle, diary, vol. 07, 1869-1870, MSS 156, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[15] Edmund Franklin Hiatt, “Autobiography of Edmund Franklin Hiatt,” Hiatt-Hiett genealogy and family history, 1699-1949; being, in particular, a record of John Hiett, Quaker, England to Pennsylvania 1699, compiled and edited by William Perry Johnson, The Jesse Hiatt Family Association: Payson, Utah. 1951

[16] Boyle, diary, vol. 07, 1869-1870, MSS 156; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, North Carolina State (Part 2) CR 375 8, box 4727, folder 1, image 115, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[17] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, North Carolina State (Part 2) CR 375 8, box 4727, folder 1, image 115, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[18] Boyle, diary, vol. 07, 1869-1870, MSS 156; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, North Carolina State (Part 2) CR 375 8, box 4727, folder 1, image 115, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[19] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, North Carolina State (Part 2) CR 375 8, box 4727, folder 1, image 115, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[20] United States, 1900 Census, North Carolina, Surry County, Mount Airy; Cactus Hill Cemetery and Other Cemeteries: A List of African-American Deaths and Burials From 1903 to 1913 According to the records At Moody Funeral Home, Compiled by Martha Rowe Vaughn, Surry County Digital Heritage, 2004.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.