Burdette, Ethel Irene Wells

Biography

Ethel Irene Wells Burdette spent her life living on the economic margins at the height of racialized segregation in the United States. She and her husband William were described as “mulatto” (people of mixed racial descent) in the 1920 census, but where nonetheless subject to full racial discrimination because of their Black African ancestry. [1] William and Ethel were two of three Black converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, baptized on the same day in 1914 in Chester County, Pennsylvania where William worked in the coal mines. Ethel and William subsequently moved to West Virginia coal country where William again worked in the mines. He would die there at a county poor farm during the Great Depression while Ethel simply disappeared from public records.

Ethel Wells was born to Emma Johnson and Edward Wells on 2 December 1885 in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, in the southwest corner of the state. [2] The scant documents that describe Ethel’s early life indicate that both of her parents had moved from Maryland before Ethel was born. [3] Ethel’s parents had likely traveled by train along one of Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s main lines. In fact, each of Ethel’s documented residences was a stop along one of the B&O Railway lines. [4]

At some point in her late twenties Ethel made her way to Girard, Ohio, roughly one hundred miles northwest across the Ohio border. The train ride there would have been uncomfortable and frightening despite Ethel’s possible lighter skin tone. Black and mixed-race women were restricted at the time from using the “ladies’ cars.” [5] These cars existed to provide comfortable accommodations and protection to women traveling alone or with a companion. [6] In 1896, the Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson upheld a Louisiana State law that enshrined the principle of “separate but equal” nationwide. Homer Plessy, the litigant in the case, was arrested for buying a first-class train ticket on a train car meant only for white people. Plessy was of mixed racial descent and was only one eighth black. [7] The Supreme Court nonetheless ruled against him and in doing so enshrined hypodescent (the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union to the subordinate group) as the law of the land. The court set a damaging precedent that stalled progress on African American rights and allowed racist policies and practices to multiply and escalate nationwide.

While the country experienced significant growth due to the expansion of the railroad, Black men and women were held back from reaping the resulting economic benefits. The train thus became a symbol in Black culture of national progress that simultaneously left them behind. It immobilized African Americans, both socially and economically, while it carried the nation forward. [8]

When Ethel came of age and entered the workforce, she did so as a domestic servant, this despite being an educated woman. During the early 1900s, the number of Black female domestic servants rose nationwide while the number of white female domestic servants significantly decreased. Although both Black women and men experienced racial restrictions in the workforce, Black women felt the impact more acutely. Employers devalued the labor of African American women by paying them lower than average wages and withholding benefits. [9]

While living and working in Ohio, Ethel met a man named William Burdette, who worked as a laborer on the railroad. Ethel married William on 2 June 1913. [10] To accommodate William's transition from railroad laborer to coal miner, Ethel and William soon relocated to Alleghany County, Pennsylvania, where the coal mining industry thrived. [11]

Ethel and William likely learned of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for the first time in Alleghany County, Pennsylvania. Matthew Barnes, a local Latter-day Saint coal miner, probably introduced them to the growing religion, as he was known to share the Latter-day Saint message with anybody who would listen, even at the bottom of a coal mine. [12] Ethel and William possibly lived with Ethel’s mother in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, shortly after their marriage, only four miles from West Mifflin, where Matthew Barnes lived. [13]

Barnes baptized William and Ethel on 10 June 1914, along with another Black coal miner, Levi Hamilton.

Four days later, on 14 June 1914, fellow Latter-day Saint Edward Smith confirmed Ethel as a member of the faith, and Barnes confirmed William. Ethel and William Burdette thus became official members of the New England Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when Ethel was twenty-eight, and William was forty-four years old. [14]

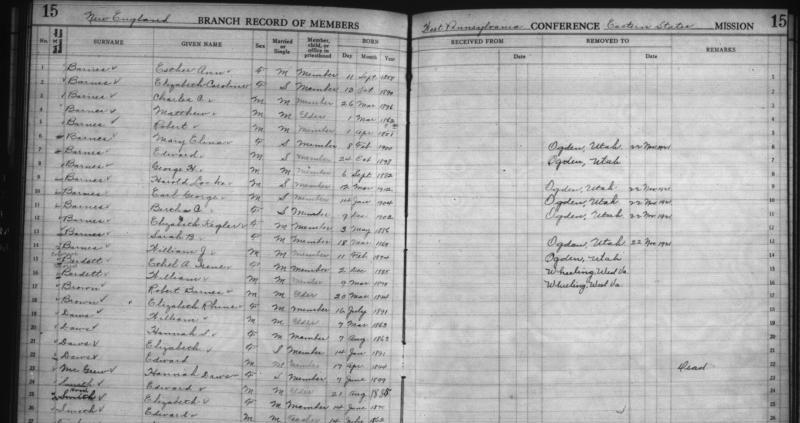

The New England Branch was organized on 22 March 1897 and named after an area in West Mifflin, Alleghany, Pennsylvania, the location of most of the members at the time. [15] William and Ethel’s names appear on only two records for the branch, leaving the details of their church activity in Pennsylvania difficult to assess. Although their baptism and confirmation record does not identify their race, a subsequent membership record includes the word “colored” written above each of their names, a margin note that was not required but sometimes included in Latter-day Saint records for those of African descent. [16]

William and Ethel had a daughter, Lucille, in about 1915 while living in Pennsylvania. [17] By early 1920, the Burdette family lived on Plum Run Road in the Midland Mine Blocks, owned by the Pittsburgh Coal Company, where William worked as a coal miner. Ethel’s sister, also married to a coal miner, lived next door to the Burdettes. [18] It is unclear how involved the Burdettes were in church services in Pennsylvania. After 1920, they lived almost forty miles from where the Latter-day Saint branch held its meetings. Maintaining activity while living so far away would have been challenging if they did not have the means to travel.

Regardless of how often they could attend church, Ethel and William maintained enough contact with the New England branch for the branch clerk to be aware when they relocated to West Virginia. After moving to West Virginia, Ethel and William established contact with Latter-day Saints there, a clear indication of their ongoing devotion to their new faith. The second of two documents that recorded their membership in the New England Branch includes a notation about their relocation to Wheeling, West Virginia. A submission to the society pages of a Pennsylvania newspaper, The Daily Notes, reveals that the Burdettes lived in West Virginia by late 1920. [19]

The conflicts and conditions of the mining industry in the northern and central parts of Appalachia’s coal mining region likely prompted the Burdettes’ move to West Virginia. [20] In West Virginia, coal companies favored Black miners because they were generally not unionized. Unions struggled to establish a foothold in West Virginia. In 1920, coal companies there preferred non-union workers so that they could pay lower wages than union rates. Coal companies often recruited Black workers to create a workforce that would defeat strikes and add to the antagonism that already existed between races. Nearly half of all new coal mining jobs created from 1920 to 1930 went to Black miners, William being one of them. [21]

The New England Branch church record for the Burdettes reveals the location of their move without indicating any branch or congregation they would be joining once in West Virginia. While the Burdettes are absent from any records for the Wheeling Branch, which existed from 1923 to 1924, they do appear in an undated record for the McMechen Branch, located only six miles from Wheeling. The entry for Ethel and William appears in the Statistical and Genealogical Record for members of the McMechen Branch. Under the column for remarks, a clerk or missionary scrawled the word “colored,” a written reminder that white was deemed normal in LDS records and Black was marked with a note of difference. At some point, the membership entry for Ethel and William was crossed out, possibly indicating death, movement to another branch, or that their membership had been copied into another ledger. [22]

A Wheeling, West Virginia City directory shows Ethel and William living there as late as 1926, with William working as a miner. [23] After 1926, the fates of Ethel and the couple’s daughter Lucille remain a mystery, as their names no longer appear in surviving sources. For William, the remainder of his life turned somber. At some point between 1926 and 1929, William’s health took a turn for the worse. In early 1929, William began treatment for chronic endocarditis, an infection of the heart’s valves, and nephritis, a type of kidney disease. [24] He would have been fifty-nine when these illnesses required treatment. Coal mining caused many health problems for miners, with Black miners being especially affected because of the depravations they experienced regarding proper housing, nutritious foods, and access to quality health care. [25] With the Great Depression just setting in, not having the physical ability to work was certainly a devastating blow for William and his family.

Given the socioeconomic factors working against Black people in the 1930s, William’s chances for survival were bleak. William became a resident of the Ohio County Home, also known as a poor farm. [26] Poor farms were places where people, whether young or old, went to live when no other option was available to them. [27] By the 1920s, poor farms had become highly controversial and only became more so due to overcrowded conditions during the Depression. Politicians highlighted the deplorable circumstances at the nation’s poor farms in an effort to galvanize support for the Social Security Act, a signature New Deal reform. [28] William was marked as married on the 1930 census when he resided at the poor farm, a likely indication that Ethel was still alive but unable to care for him. [29]

William resided at the Ohio County Home Farm in Liberty, West Virginia, at the time of his death on 5 March 1931. His death record specified that he was now single, perhaps an indication that he and Ethel had divorced or that Ethel had predeceased him. William was buried in the Stone Church Cemetery on 9 March 1931, although the exact location is unknown. Ethel’s death date, location of where she died, and place of burial remain unknown. [30]

By Jaclyn D. Pruett

[1] United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Alleghany County, Mifflin Township.

[2] Ohio, Trumbull County, Marriages, 1774-1993, William Birdett and Ethel Wells, 2 June 1913; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection Part 2, Segment 2, New England Branch, CR 375 8, box 5298, folder 2, image 10, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter CHL).

[3] United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Washington County, Chartiers Township; Pennsylvania, Washington County, Marriages, 1852-1968, Frank Goines and Pearl Crable, 17 July 1917; The city of Emma Johnson’s birth was recorded on the marriage license of Ethel’s sister, Pearl Crable.

[4] Elmer, Walter F., and Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Company. Map of the Baltimore and Ohio Rail Road with its branches and connections. Baltimore, 1878.

[5] The race of Ethel, William, and Lucille was recorded as “mulatto” on the 1920 Census; United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Alleghany County, Mifflin Township; Miriam Thaggert, Riding Jane Crow: African American Women on the American Railroad (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2022), 52.

[6] Thaggert, Riding Jane Crow, 52; Ethel, William, and Lucille were recorded as mulatto on the 1920 Census; United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Alleghany County, Mifflin Township.

[7] Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896).

[8] Thaggert, Riding Jane Crow, 12-14.

[9] Joe William Trotter, Jr., Workers on Arrival (Oakland: University of California Press, 2019), 91-92.

[10] Ohio, Trumbull County, Marriages, 1774-1993, William Birdett and Ethel Wells, 2 June 1913.

[11] William H. Turner, Edward J. Cabbell, Blacks in Appalachia (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1985), 161.

[12] L.M. Anderson, From These Hills and Valleys: A Brief History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Southwestern Pennsylvania (Wilkinsburg, PA: Hoechstetter Printing, 1986), 60.

[13] Pennsylvania, Washington County, Marriages, 1852-1968, Frank Goines and Pearl Crable, 17 July 1917; The residence of Ethel’s mother was recorded on the marriage license of Ethel’s sister, Pearl Crable; United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Alleghany County, Mifflin Township.

[14] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection Part 2, Segment 2, New England Branch, CR 375 8, box 5298, folder 2, image 10, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter CHL).

[15] Anderson, From These Hills and Valleys: A brief history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in southwestern Pennsylvania, 4.

[16] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Pennsylvania State Part 2, Segment 1, New England Branch, CR 375 8, box 5298, folder 1, image 357 and 366, CHL.

[17] United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Washington County, Chartiers Township.

[18] United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Washington County, Chartiers Township.

[19] “Mrs. Ethel Birdittie and small daughter Lucille” The Daily Notes (Canonsburg, Pennsylvania), 6 November 1920, 3.

[20] See William Burdette’s Biography for more information on how and why the family relocated. Jaclyn D. Pruett, “William A. Burdette,” Century of Black Mormons.

[21] William H. Turner, Edward J. Cabbell, Blacks in Appalachia (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1985), 160-165.

[22] Wheeling Branch, Mormon Places; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, West Virginia State Part 2, McMechen Branch, CR 375 8, image 7,CHL.

[23] Wheeling, West Virginia, Directories, 1926, 1822-1995.

[24] West Virginia, State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, District No. 3501-91, Series No. 194, William Burdetti; “Glomerulonephritis (GN),” Cleveland Clinic, 2023, https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/16167-glomerulonephritis-gn, accessed 20 June 2024.

[25] Joe William Trotter, Jr., African American Workers and the Appalachian Coal Industry (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2022), x.

[26] United States, 1930 Census, West Virginia, Ohio County, Liberty District.

[27] “Many Inmates in Need of Attention” Evening Journal (Martinsburg, West Virginia), 21 April 1921, 11.

[28] “The humane principles of Christianity” The Independent-Herald (Hinton, West Virginia), 1 November 1934, 5.

[29] United States, 1930 Census, West Virginia, Ohio County, Liberty District.

[30] West Virginia, State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, District No. 3501-91, Series No. 194, William Burdetti; Email correspondence between author and Wheeling, West Virginia History Specialist, Sean Duffy, 24 May 2024

<h3 id="documents">Documents</h3>

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.