Burdette, Ethel Wells

Biography

John Stewart Knight was beset by opposition for most of his life. As the child of a prominent Confederate army deserter turned rebel who defied social norms in his familial relationships, John Stewart must have grown accustomed to being the subject of gossip from an early age. His father had married a white woman named Serena and later maintained a relationship with John Stewart’s mother, a formerly enslaved woman named Rachel Knight. As a mixed-race man and suspected homosexual, John Stewart faced challenges throughout his life. Eventually he followed in the footsteps of his mother and two siblings and joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at the age of twenty-six, perhaps in an attempt to find acceptance and a sense of community through faith. His life nonetheless ended violently when he was 52 years old.

John Stewart’s father, Newton Knight, was a well-known soldier who gained attention in the spring of 1864 when he led a company of deserters in open rebellion against the Confederacy.[1] John Stewart’s mother Rachel Knight, became anintegral ally in Newton’s operation and used her skills as an herbalist and her position inside Confederate homes to assist Newton and his army. With the help of Rachel and others, Newton was able to resist and successfully overthrow Confederate authorities in Jones County, Mississippi. His defiance was so legendary that it has become the subject of articles, books, and even a major motion picture, Free State of Jones (2016) starring Matthew McConaughey as Newton and Gugu Mbatha-Raw as Rachel.[2]

Following their victory, Rachel and Newton’s relationship turned romantic. Despite already having a white family including a wife and children, Newton entered a second common-law marriage with Rachel.[3] Though John Stewart left no indication as to his feelings about his father’s public legacy or the non-traditional family he grew up in, those aspects of his upbringing certainly played a role in his sense of self and must have had a major influence on the way he viewed the world and how outsiders viewed him.

John Stewart Knight was born on 10 May 1868 in Jones County, Mississippi.[4] Although he grew up in a separate home from his father and white half-siblings, they all lived together on the same 160-acre plot of land in southwest Jasper County, Mississippi. John Stewart spent his youth in a home that sat adjacent to that of his father’s white family. His mother raised him alongside his four siblings all of whom were likely kept busy on the family farm.[5]

Although surviving sources do not indicate the nature of John Stewart’s relationship with his white half siblings, family tradition does suggest that the two families lived alongside each other in relative harmony. John Stewart’s older full siblings did experience rejection from the local public school which refused to allow “Negroes” to attend. In response, white relatives brought home school materials for the benefit of their half-siblings.[6]

The social exclusion of the Knight family extended to other aspects of community life as well. Outsiders described the Knight family in negative terms, sometimes referring to a harem-like lifestyle grounded in race mixing. John Stewart and his family were sometimes subject to gossip and ostracization as were their white half-siblings. The latter were sometimes called “White-Negroes” or the “Knight Negroes” and were frequently under scrutiny. Outsiders sometimes labeled them “Freejacks,” a term that meant that neither the Black nor white communities accepted them as their own. As a result, John Stewart and his family withdrew for the sake of safety and freedom from judgment which only made the animosity and curiosity worse.[7]

As he grew older, John Stewart as well as his siblings worked as farm laborers on their family’s plot of land to help provide for themselves.[8] Growing up in such a closed circle of relatives, largely isolated from the outside world, may account for John Stewart’s later passion for socializing and meeting new people.

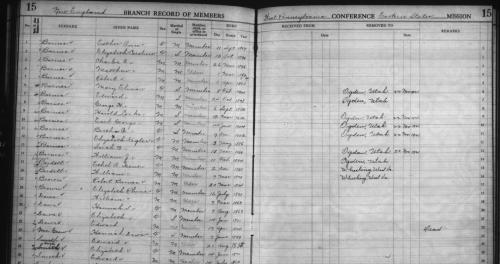

On 8 April 1894, at the age of twenty-six, John Stewart joined his two siblings and mother in becoming a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Elder Joshua Arthur Blackwell from Sevier County, Utah, baptized him and Elder William David Rencher from Springerville, Arizona, confirmed him on the same day. His mother, half-sister Fannie, and sister Martha Ann had been baptized almost a decade earlier.[9]

It is not clear what motivated John Stewart to convert after so much time had passed since his family members had been baptized. Perhaps his mother was influential in his decision, although she had died five years earlier. His sisters may have encouraged his decision too. His own social proclivities likely also factored into the decision to join a tightknit faith community in search of belonging. Or he may have witnessed the good that having a sense of faith did for the people in his circle of influence and wanted that same comfort in his life.[10]

Sometime between 1900 and 1910 John Stewart may have married even though no evidence of such a union survives. His marital status changes from single in the 1900 census to widower in 1910, an indication that his marriage must have been short lived and that his wife must have passed away within ten years of their marriage. The 1920 census again labels him a widower. There is no evidence that John Stewart fathered any children.[11]

John Stewart had a lighter complexion than some in the Black community and was sometimes labeled a "mulatto,” including on his Latter-day Saint baptismal record. As a result, John Stewart may have aligned more easily with white society as an adult.[12] He was known for being a well-dressed and well-to-do man who preferred to blend in with white society. According to family tradition, he was not seen in public in the company of women and he did not marry, even though the census records suggest otherwise. When he left the Knight family estate, he may have married and been left a widower but if so, he did not remarry and lived alone for the majority of his adult life. Family tradition suggests that he was gay but not openly so and no evidence exists to confirm or deny that claim.[13]

John Stewart's death was shrouded in mystery as much was some aspects of his life. On 29 November 1920 his mutilated body was found in Jasper County, Mississippi, where he had lived most of his life. The man who found John Stewart reported that his body seemed as though it had been dead for several days. Those who saw John Stewart’s corpse before his burial described his head being “partially shot off” and reported that his body had been brutally hacked by a weapon resembling an ax. His neighbor and paternal cousin, Sharp Wellborn, was arrested on 6 December and later charged with John Stuart’s murder.[14]

The motive behind John Stewart’s death was obscured by rumors. Wellborn was accused of robbery but townspeople were suspicious that it was a racially-motivated act tied to an incident that John Stewart had been involved in around thatsame time. Local residents, including Sharp Wellborn, had accused John Stewart of raping a white woman in the community. However, after his death, John Stewart’s family argued that he had actually intervened to stop the assault rather than committing it. If the family’s assertions are correct, John Stewart’s death would match that of thousands of other Black men who were lynched in the postbellum South for rumored assaults on white women.[15] Although Sharp Welborn was convicted of John Stewart’s murder and sent to prison, the Lieutenant Governor released him only three years later while the Governor was out of state.[16]

John Stewart Knight’s body was laid to rest alongside family members within the Knight Family Cemetery in Jasper County, Mississippi.[17]

By Wesley Acastre

With research assistance from Michael Benson

[1] Victoria E. Bynum, The Free State of Jones, Movie Edition: Mississippi's Longest Civil War. (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016), 166.

[2] “Martha Wheeler, Eye-Witness to the Free State of Jones,” Renegade South, 2 July 2017.

[3] “The True Story of the Free State of Jones,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 2016.

[4] United States, 1870 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County, Beat 4; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, image 102, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[5] “Part 2: Yvonne Bivins on the History of Rachel Knight,” Renegade South, 11 September 2009.

[6] Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer, The State of Jones (New York: Anchor Books, 2009), 259, 283-4.

[7] “Newt Knight’s ‘white negroes’ Part one,” Laurel Leader Call, 12 July 2018.

[8] United States, 1880 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County, Beat 4.

[9] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, images 23-24, 102, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[10] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, images 23-24, 102, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[11] United States, 1900 Census, Mississippi, Jones County; United States, 1910 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County; United States, 1920 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County.

[12] George P. Rawick, The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography. Vol. Supplement, Series 1. Vol. X: Mississippi Narrative Pt. 5 (Westport: Greenwood Press, 1979); Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, image 102, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[13] Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 283; “Part 3: Yvonne Bivins on the History of Rachel Knight,” Renegade South, 15 September 2009.

[14] Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 283.

[15] Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 283.

[16] “The Court Advances Row on Pardons,” The Free Press (Poplarville, Mississippi) 27 September 1923.

[17] John Stewart Knight, Findagrave.com.

<h3 id="documents">Documents</h3>

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.