Burdette, William A.

Biography

William A. Burdette and his wife Ethel were two of three Black converts to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, baptized in 1914 in Chester County, Pennsylvania. William spent the bulk of his life working as a coal miner in the Mid-Atlantic states and spent a hardscrabble life on the economic margins before he died in 1931.

William was born on 9 March 1870 in Casey County, Kentucky, as the fourth of Anderson Burdett and Ann Haggard’s six children.[1] At least seven spelling variations for Burdett exist within the records discovered for William thus far. The many different spellings most likely exist because William could not read or write. He signed his marriage certificate with “his mark,” and several other records confirm that he was illiterate.[2] As a result, scribes and other notetakers would have spelled his name phonetically because he was unable to spell it for them.[3]

William’s ancestry likely included a man named Enoch Burdett, a prominent white enslaver in Casey County, Kentucky, who was rumored to give land to some of those he formerly enslaved. Enoch Burdett was most likely William’s grandfather. If true, it would help to account for the fact that William’s father, Anderson, became a significant landholder in the Reconstruction South. Sometime between the 1870 Census and the 1880 Census, Anderson’s occupation changed from ‘farm hand’ to ‘farmer,’ indicating that he probably went from working as a laborer on someone else’s land to owning and farming his own land.[4]

In the wake of emancipation, land ownership represented the reality of freedom to the formerly enslaved and proved their ability to overcome any obstacle.[5] From about 1865 to 1910, hundreds of thousands of Black people from rural areas, mainly in the South, became landowners. Even still, the attempts by the federal government to help formerly enslaved Black people acquire land and retain it were feeble and, for the most part, ineffective.[6] Many Black farmers gained land through working relationships already in place with white farmers.[7] In Anderson’s case, Enoch Burdett was one of 109 enslavers in Casey County in 1860 and the owner of 11,000 acres of land. He was Anderson’s neighbor and quite possibly his father.[8] Enoch’s connection to Anderson is likely how Anderson, a Black man in 1870s Kentucky, came to own 190 acres of land.[9]

Casey County lore supports the idea that Enoch was Anderson’s father. Local tradition indicates that Anderson was the son of either Enoch Burdett or Enoch’s father through a sexual relationship with Anderson’s enslaved mother. Anderson presumably inherited his land from Enoch simply because he was Enoch’s son.[10]

Other sources substantiate the possibility that Enoch was Anderson’s father. Anderson would have been eighteen years old in 1840 and is likely represented by the tally mark for a male in the “free colored persons 10 & under 24” category on the census for the then forty-year-old Enoch Burdett’s household. One of the four enslaved women in the same household was the correct age to have a child, making it a possibility that she was Anderson’s mother.[11] By his death in 1877, Enoch owned 25,000 acres of land and was said by some to have given land to those he had enslaved.[12]

The connection between Anderson Burdett and Enoch Burdett may have helped to establish Anderson as a farmer after the Civil War and explains why Anderson and his children were at times marked as “mulatto” on records.[13] It also helps to explain how William Burdette was born into a Black landowning family in the Reconstruction South.

By 1877, when William was still a child, all federal troops were removed from the South, effectively ending Reconstruction. By 1883, Supreme Court rulings had reversed the Civil Rights Act of 1875, further eroding rights for Black people.[14] With no more federal oversight, white people in the South began to do away with the few opportunities given to formerly enslaved people. They began to implement a caste system based on race, undoing any progress made during Reconstruction. Legislatures in the southern states began to put laws into place–known as Jim Crow laws–that regulated all aspects of Black people’s lives and made sure they had minimal contact with white people.[15] The absence of any kind of protection for Black people, the increased racial tensions in the South, and various natural disasters all led to a mass exodus of Black people from Southern states, known as the Great Migration. Many people made their way to rural industrial regions, working in lumber, railroad, or mining industries.[16] William Burdett fit that mold.

Sometime between 1880 and 1900, William became one of thousands of Black Southerners searching for a better life. By 1900, William lived in Leadsville, West Virginia, and worked as a day laborer. Twenty Black lodgers, including William, lived in the same residence. Fourteen were day laborers, while the other six were railroad graders, making it highly likely that they were all employed by the same railroad company.[17] The number of Black migrants to West Virginia dramatically increased during the railroad expansions of the 1890s and early 1900s. Black railroad workers laid track for all the major railway lines throughout the region.[18] Constructing and maintaining railroads was tedious, back-breaking, and highly dangerous work. Native-born white men avoided this kind of work due to the difficulty, danger, and low wages involved, forcing railroad companies to employ mainly Black and immigrant workers. Performing this kind of “section” work on railroads meant living in isolated or mobile camps and a life disrupted by frequent relocations. [19] This could be why William is absent from the 1910 Census.

Ohio had become an important central point for transit between port cities in the Northeast and Midwest and required thousands of workers to maintain the nearly 9,000 miles of railway track spanning the state.[20] Perhaps working as a railroad laborer eventually took William to Girard, Ohio, where he resided when he married Ethel Irene Wells on 2 June 1913.[21] Life as a transient railroad laborer would not have been conducive to raising a family. The camps and towns that railroad workers lived in were rough and dangerous and not places where married women and children would be safe or welcome.[22] Life on the move would have meant that William was away from his family for extended periods and unable to provide the physical support and protection expected of a husband. Coal company policies, in contrast, made it possible for families to remain together. Coal companies recognized that married men stayed in one place longer and worked harder to support their families, thus making them ideal workers. The desire to leave the life of a railroad laborer and become more settled could be why, by 1914, William and Ethel had settled in Alleghany County, Pennsylvania, where the coal mining industry then flourished.[23]

William and Ethel likely heard of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints for the first time in Alleghany County, Pennsylvania. Matthew Barnes, a fellow coal miner, likely introduced them to the growing religion, as he was known to share the Latter-day Saint message with anybody who would listen, even at the bottom of a coal mine.[24] William and Ethel possibly lived with Ethel’s mother in McKeesport, Pennsylvania, shortly after their marriage, only four miles from West Mifflin, where Matthew Barnes lived.[25]

Barnes baptized William and Ethel on 10 June 1914. Four days later, Barns confirmed William as a member of the faith, and fellow Latter-day Saint Edward Smith confirmed Ethel. William and Ethel Burdett thus became official members of the New England Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints when William was 44 years old and Ethel was 29. Black coal miner, Levi Hamilton, also joined the branch around the same time, making three Black members in the small congregation.[26]

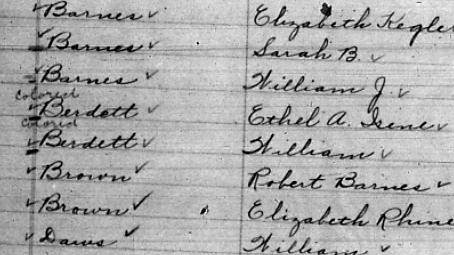

The New England Branch was organized on 22 March 1897 and seems to have been named after the main area in West Mifflin, where most of the members at the time were located.[27] William and Ethel’s names appear on only two records for the branch, leaving the details of their church activity in Pennsylvania unknown. Although their baptism and confirmation record does not identify their race, a subsequent membership record has the word “colored” written above each of their names, a typical margin note in Latter-day Saint records for those of African descent.[28]

William and Ethel had a daughter, Lucille, in about 1915 while living in Pennsylvania.[29] By early 1920, the Burdett family lived on Plum Run Road in the Midland Mine Blocks, owned by the Pittsburgh Coal Company, where William worked as a coal miner. Ethel’s sister, also married to a coal miner, lived next door to the Burdetts.[30] It is unclear how active or involved the Burdetts were in church services in Pennsylvania. After 1920, they lived almost forty miles from where the Branch held its meetings. Maintaining activity while living so far away would have been challenging if they did not have the means to travel.

William and Ethel nonetheless maintained enough contact with the New England branch for the branch clerk to be aware when they relocated to West Virginia. After moving to West Virginia, William and Ethel established contact with Latter-day Saints there, an indication of their ongoing connection to their new faith. The second of two documents that recorded their membership in the New England Branch includes a notation about their relocation to Wheeling, West Virginia even though it does not indicate a date. A submission to the society pages of a Pennsylvania newspaper, The Daily Notes, nevertheless reveals that the Burdetts lived in West Virginia by late 1920.[31]

Unionism had caught on in states in the northern and central parts of Appalachia's coal mining region, and Pennsylvania was one such state.[32] In 1920, coal mining operators in western Pennsylvania cut the wages of their employees significantly, resulting in strikes and shutdowns. Although many unions refused to allow Black members to join, the strikes and wage cuts would have still impacted William. Whether or not William joined a union, coal companies played racial and ethnic groups off of each other. William would have had an incentive to be a strikebreaker to gain one of the better positions typically denied to Black miners.[33]

In West Virginia, coal companies favored Black miners because they were generally not unionized. Unions struggled to establish a foothold in West Virginia. In 1920, coal companies there preferred non-union workers so that they could pay lower wages than union rates. Coal companies often recruited Black workers to create a workforce that would defeat strikes and add to the antagonism that already existed between races. Nearly half of all new coal mining jobs created from 1920 to 1930 went to Black miners, William being one of them.[34]

The New England Branch church record for the Burdetts reveals the location of their move without indicating any branch or congregation they would be joining once in West Virginia. While the Burdetts are absent from any records for the Wheeling Branch, which existed from 1923 to 1924, they do appear in records for the McMechen Branch, located only 6 miles from Wheeling. The entry for William and Ethel appears in the Statistical and Genealogical Record for members of the McMechen Branch. Under the column for remarks, a clerk or missionary scrawled the word “colored,” a written reminder that white was deemed normal in LDS records and Black was marked with a note of difference. At some point, the membership entry for William and Ethel was crossed out, possibly indicating death, movement to another branch, or that their membership had been copied into another ledger.[35]

A Wheeling, West Virginia City directory shows William and Ethel living there as late as 1926, with William working as a miner.[36] After 1926, the fates of Ethel and the couple’s daughter Lucille remain a mystery, as their names no longer appear in surviving sources. For William, the remainder of his life turned somber. At some point between 1926 and 1929, William’s health took a turn for the worse. In early 1929, William began treatment for chronic endocarditis, an infection of the heart’s valves, and nephritis, a type of kidney disease.[37] He would have been fifty-nine when these illnesses required treatment. Coal mining caused many health problems for miners, with Black miners being especially affected because of the depravations they experienced regarding proper housing, nutritious foods, and access to quality health care.[38] With the Great Depression just setting in, not having the physical ability to work was certainly a devastating blow for William.

Given the socioeconomic factors working against Black people in the 1930s, William’s chances for survival were bleak. William became a resident of the Ohio County Home, also known as a poor farm.[39] Poor farms were places where people, whether young or old, went to live when no other option was available to them.[40] By the 1920s, poor farms had become highly controversial and only became more so due to overcrowded conditions during the Depression. Politicians highlighted the deplorable circumstances at the nation’s poor farms in an effort to galvanize support for the Social Security Act, a signature New Deal reform.[41] William was marked as married on the 1930 Census when he resided at the poor farm, indicating that Ethel was still alive but unable to care for him.[42]

William Burdett died on 5 March 1931, four days shy of his sixty-first birthday. He resided at the Ohio County Home Farm in Liberty, West Virginia. His death record indicates that he was single at the time of his death; the informant listed on the death certificate is an unknown person named W.C. Murray, suggesting that he died without family nearby. His death certificate indicates hypostatic pneumonia was a contributing factor to his death, a condition usually caused by being bedridden for a prolonged period of time. William thus not only died alone in a county poor house, but his death was most likely painful and drawn out. William Burdett was buried in the Stone Church Cemetery on 9 March 1931, although the exact location is unknown.[43]

By Jaclyn D. Pruett

[1] United States, 1880 Census, Kentucky, Casey County, District 21;West Virginia; State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, District No. 3501-91, Series No. 194, William Burdetti; Ann Haggard’s name is listed various ways throughout her life: Ann or Annie Haggard, Haggart, Hagered; Anderson Burdett’s name is listed various ways over time: Anderson Burdett, Harper Burdett, Harpe Burdutt, Anderson Birdett, Andrew Berdett, Harper Burdettia, Harp Burdetti.

[2] United States, 1870 Census, Kentucky, Casey County, Liberty Precinct; United States, 1880 Census, Kentucky, Casey County, District 21; Ohio, Trumbull County, Marriages, 1774-1993, William Birdett and Ethel Wells, 2 June 1913.

[3] According to census records from 1870 and 1880, none of William’s family could read or write; William Burdett’s last name is listed various ways across time and space: Burdutt, Burditt, Birdett, Berdett, Birdettia, Berdettia, Burdetti.

[4] United States, 1870 Census, Kentucky, Casey County, Liberty Precinct; United States, 1880 Census, Kentucky, Casey County, District 21.

[5] Roy W. Copeland, “In the Beginning: Origins of African American Real Property Ownership in the United States,” Journal of Black Studies 44, no. 6 (September 2013), 646, 661.

[6]Thomas W. Mitchell, From Reconstruction to Deconstruction: Undermining Black Land Ownership, Political Independence and Community through Partition Sales of Tenancies in Common (Madison: Land Tenure Center at the University of Wisconsin, 2000).

[7] Bruce J. Reynolds and United States Rural Business/Cooperative Service, Black Farmers in America, 1865-2000: The Pursuit of Independent Farming and the Role of Cooperatives. (Washington D.C: U.S. Dept. of Agriculture, Rural Business-Cooperative Service, 2002), 4.

[8] United States, Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880, Kentucky, Casey County, District 21; Kenneth H. Williams, James Russell Harris, “Kentucky in 1860: A Statistical Overview,” The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 103, no. 4 (2005), 746.

[9] United States, Selected Federal Census Non-Population Schedules, 1850-1880, Kentucky, Casey County, District 21.

[10] Willie Moss Watkins (Compiler), The Men, Women, Events, Institutions & Lore of Casey County, Kentucky. (Louisville, KY: Standard Printing, 1939), 58, 68, 93-94; Anderson eventually passed on his land to his daughter and son-in-law, Betty and Frank Wilhite. A local man from Casey County, Kentucky gathered stories from locals to record the “history” of the County. Some of the information found within the compilation can be confirmed by other more reliable sources, however, there are accounts given that seem to contradict each other.

[11] United States, 1840 Census, Kentucky, Casey County, Liberty.

[12] “Enoch Burdett,” Interior Journal (Stanford, Kentucky), 26 January 1877, 3; The Men, Women, Events, Institutions & Lore of Casey County, Kentucky, 50.

[13] The race of Anderson Burdett’s family was recorded as “mulatto” on the 1880 Census. William, Ethel, and Lucille Burdett were recorded as “mulatto” on the 1920 Census. According to The Men, Women, Events, Institutions & Lore of Casey County, Kentucky, some of William’s nieces were considered “very white and good looking.”

[14] “Jim Crow Museum Timeline,” Ferris State University, 2023.

[15] Isabel Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America’s Great Migration (New York: Random House, 2010), 40.

[16] Wilkerson, The Warmth of Other Suns, 532; Mitchell, From Reconstruction to Deconstruction, 509; Joe William Trotter, Jr., African American Workers and the Appalachian Coal Industry (Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2022), xv.

[17] United States, 1900 Census, West Virginia, Randolph County, Leadsville District.

[18] Joe William Trotter, Jr., “Race, Class, and Industrial Change: Black Migration to Southern West Virginia, 1915-1932,” in Joe William Trotter, Jr., ed., The Great Migration in Historical Perspective: New Dimensions of Race, Class, and Gender (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 48.

[19] Eric Arnesen, Brotherhoods of Color: Black Railroad workers and the Struggle for Equality (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 6.

[20] Stephanie Michaels, “All Aboard! Ohio Railroad History,” Ohio Memory, published 4 August 2017, https://ohiomemory.ohiohistory.org/archives/3405.

[21] Ohio, Trumbull County, Marriages, 1774-1993, William Birdett and Ethel Wells, 2 June 1913.

[22] Arnesen, Brotherhoods of Color, 6, 13.

[23] William H. Turner, Edward J. Cabbell, Blacks in Appalachia (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1985), 161.

[24] L.M. Anderson, From These Hills and Valleys: A brief history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in southwestern Pennsylvania (Wilkinsburg, PA: Hoechstetter Printing, 1986), 60.

[25] Pennsylvania, Washington County, Marriages, 1852-1968, Frank Goines and Pearl Crable, 17 July 1917; The residence of Ethel’s mother was recorded on the marriage license of Ethel’s sister, Pearl Crable; United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Alleghany County, Mifflin Township.

[26] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection Part 2, Segment 2, New England Branch, CR 375 8, box 5298, folder 2, image 10, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter CHL)

[27] Anderson, From These Hills and Valleys: A brief history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in southwestern Pennsylvania, 4.

[28] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Pennsylvania State Part 2, Segment 1, New England Branch, CR 375 8, box 5298, folder 1, image 357 and 366, CHL.

[29] United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Washington County, Chartiers Township.

[30] United States, 1920 Census, Pennsylvania, Washington County, Chartiers Township.

[31] “Mrs. Ethel Birdittie and small daughter Lucille” The Daily Notes (Canonsburg, Pennsylvania), 6 November 1920, 3.

[32] William H. Turner, Edward J. Cabbell, Blacks in Appalachia (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1985), 163.

[33]Eileen Mountjoy, “That Magnificent Fight For Unionism,” Indiana University of Pennsylvania, 2007-2024, accessed June 19, 2024; Warren C. Whatley, “African-American Strikebreaking from the Civil War to the New Deal,” Social Science History 17, no. 4 (Winter 1993): 537.

[34] Turner and Cabbell, Blacks in Appalachia, 160-165.

[35] Wheeling Branch, Mormon Places; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, West Virginia State Part 2, McMechen Branch, CR 375 8, image 7,CHL.

[36] Wheeling, West Virginia, Directories, 1926, 1822-1995.

[37] West Virginia, State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, District No. 3501-91, Series No. 194, William Burdetti; “Glomerulonephritis (GN),” Cleveland Clinic, 2023, accessed 20 June 2024.

[38] Trotter, Jr., African American Workers and the Appalachian Coal Industry, x.

[39] United States, 1930 Census, West Virginia, Ohio County, Liberty District.

[40] “Many Inmates in Need of Attention” Evening Journal (Martinsburg, West Virginia), 21 April 1921, 11.

[41] “The humane principles of Christianity” The Independent-Herald (Hinton, West Virginia), 1 November 1934, 5.

[42] United States, 1930 Census, West Virginia, Ohio County, Liberty District.

[43] West Virginia, State Department of Health, Division of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, District No. 3501-91, Series No. 194, William Burdetti; Email correspondence between author and Wheeling, West Virginia History Specialist, Sean Duffy, 24 May 2024.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.