Charlotte

Biography

Charlotte was an enslaved woman who lived in Franklin County, Alabama, in the northwest portion of the state, in the Tennessee River Valley. She joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sometime between November 20 and December 3, 1844, attending the small and short-lived Little Bear Creek Branch.[1]

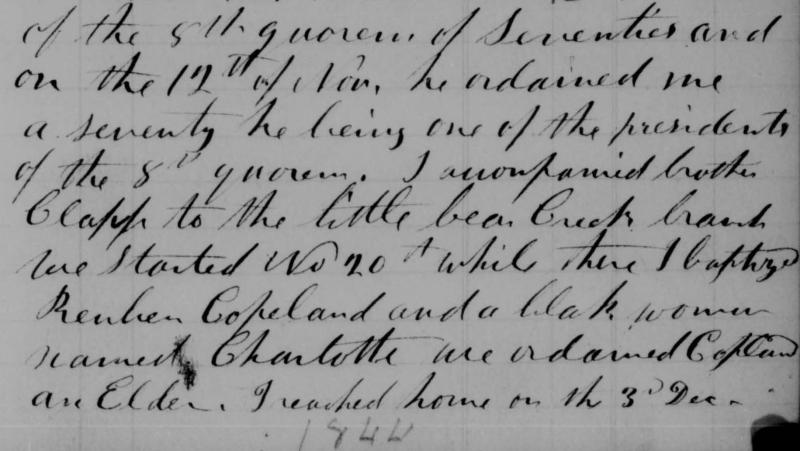

Latter-day Saint missionary John Brown’s journal is the only surviving source to mention Charlotte by name. Brown recorded that he “baptized Reuben Copeland and a black woman named Charlotte,” but failed to specify the date of the baptisms or the name of Charlotte’s enslaver.[2] Adding to the challenge of tracing Charlotte over time is the fact that in 1890, Franklin County’s courthouse burned down, destroying any records that may have shed additional light on Charlotte’s life, including marriage, birth and death records, wills, probate records, and land sales and deeds. Because of the scarcity of information about Charlotte, only an approximation of her life can be inferred from what we know about her potential enslaver, the religious life of enslaved people in the South, and the demographics of antebellum Franklin County, Alabama.

Simply because Reuben Copeland and Charlotte were baptized on the same day, Copeland is Charlotte’s most likely enslaver. Evidence suggests that Reuben’s wife Margret had already joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and now Reuben and Charlotte would too. Latter-day Saint missionary Abraham O. Smoot stayed at the Copelands when preaching to the Little Bear Creek Branch and Brown likely did too.[3]

We know of only three members of the Little Bear Creek Branch by name: Copeland, Charlotte, and the presiding elder of the branch, Joseph L Griffin. Griffin enslaved two women and two men in the 1830 census, and four people of undetermined age or gender in the 1850 Alabama Census. Though it is possible that one of Griffin’s enslaved women was Charlotte, Griffin lived several miles from Copeland, making it is less likely that Charlotte would have traveled from Griffin’s farm to be baptized with Copeland with no mention of Griffin at the baptism. By February 15, 1845, the Little Bear Creek Branch had over twenty unnamed members, one of whom also could have been Charlotte’s enslaver.[4]

Even still, Reuben Copeland is the most plausible possibility. In Franklin County, enslaved people made up about 42 percent of the population in 1840.[5] However, a partial survey of the county census indicates that only half of the heads of household in the area were enslavers. Of those, most did not own large plantations but farmed smaller acreages and enslaved three to four people. Copeland fit this pattern. He grew corn on less than forty acres and owned no slaves in the 1840 census. By 1850, however, he had acquired four enslaved people: a 35-year-old woman; two boys, ages nine and ten; and a five-year-old girl.[6] Records do not indicate whether the 35-year-old woman was Charlotte or if the three enslaved children in the household were her children. In any case, the children were probably meant to help on the farm and in the house, with the enslaved woman expected to watch over and care for them as well as perform other household and caretaking duties.

In situations like the Copeland household with few enslaved people, the slaves typically lived under the same roof as the enslavers and were more likely to follow the cultural and religious inclinations of their enslavers. But they did not do so naively. By the early nineteenth century, African Americans had made Christianity their own, often conducting preaching and prayer meetings outside the knowledge or authorization of their enslavers, celebrating the Old Testament stories of Moses freeing the Israelites. Enslaved Christians in the American South found hope in Christ, not only in a life to come, or as support for their mortal travails, but as a promise that they would be freed from bondage in the near future.[7] Because they were under more supervision, household slaves were less likely to attend such covert meetings, but the slave theology preached at them was nonetheless widespread.

Brown offers no clue as to what may have attracted Charlotte to the Latter-day Saint cause or how much choice she was given in the matter. Perhaps Charlotte simply acquiesced to the wishes of Reuben and Margaret Copeland and was baptized with Reuben. No matter her motivation, contradictions would have complicated her choice. In the very year that Brown baptized Charlotte, Methodists, who made up the majority of religious believers in Franklin County, were experiencing a secession crisis over the question of slavery.[8] There is a very good chance that the debate over the morality of slavery and the biblical status of African Americans came up in the discussions and preaching of the Latter-day Saint missionaries there. Both Brown and Smoot, the missionaries who recorded all that we know of the Little Bear Creek Branch, were from the South and would go on to own slaves in Utah Territory. Thus, Charlotte may have heard Latter-day Saint missionaries affirming typical rationalizations for slavery and white supremacy before she was baptized. However, such justifications would have been no different from what other white preachers might have said. She already would have been adept at separating the good from the bad and holding on to those things that gave her hope. Perhaps there was something in the Latter-day Saint message that affirmed to her that Jesus Christ claimed all flesh as his own and that he was no respecter of persons (Doctrine and Covenants 38:16), even if the missionaries who preached such a message contradicted those ideals.

Reuben Copeland continued to enslave people for at least another decade following Charlotte’s baptism. Copeland claimed two slaves in the 1855 Alabama census but that is the last public record to document his enslavement of other people. He appears in the 1860 census but not in the 1860 slave schedule. As a result, there are no marks of gender and age to suggest Charlotte’s continued presence in the Copeland household.[9]

As for the Little Bear Creek Branch, a February 1845 conference report is the last to mention the small Alabama congregation in any records of the Church or its missionaries.[10] No overland pioneers have been traced to the branch. If Charlotte remained religious, whether as a believer in the Latter-day Saint cause or not, she likely would have worshipped God in another setting of her choice after that.

By Ami Chopine

Primary Sources

Alabama. 1850 Alabama State Census. Franklin County. Entry for Reuben Copeland and Jo L Griffin.

Alabama. 1855 Alabama State Census. Franklin County. Entry for Ruben Copeland.

Brown, John. Reminiscences and Journal, vol. 1, 31. MS 1636. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Minutes of the first annual Conference held in the district of Alabama, Tuscaloosa county, Feb’y 15th, 1845.” Times and Seasons, vol 6 (Nauvoo, Illinois), 1845-1846, 843-844.

Smoot, Abraham O. Missionary Diary vol 1, 1836-1846. MS 896. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Harold B. Lee Library. Brigham Young University.

United States. 1830 Census. Alabama, Franklin County.

United States. 1840 Census. Alabama, Franklin County.

United States. 1850 Census. Alabama, Franklin County.

United States. 1860 Census. Alabama, Franklin County.

United States. 1850 Census, Slave Schedules. Alabama, Franklin County. Entry for Reuben Copeland.

United States. 1860 Census, Slave Schedules. Alabama, Franklin County.

United States. 1860 Census, Agriculture Schedules. Alabama, Franklin County. Entry for Reuben Copeland.

Secondary Sources

Raboteau, Albert J. Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South. New York: Oxford University Press.

West, Anson. A History of Methodism in Alabama. Methodist Episcopal Church: Nashville, Tennessee 1893.

Social Explorer Dataset (SE). Census 1840. Digitally transcribed by Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. Edited, verified by Michael Haines. Compiled, edited and verified by Social Explorer.

[1] John Brown, Reminiscences and Journal, vol. 1, 31, MS 1636, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] Brown, Reminiscences and Journal, 31.

[3] Abraham O. Smoot, Missionary Diary vol 1, 1836-1846, 222-223, MS 896, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[4] “Minutes of the first annual Conference held in the district of Alabama, Tuscaloosa county, Feb’y 15th, 1845,” Times and Seasons, vol. 6 (Nauvoo, Illinois), 1845-1846, 843-844.

[5] Social Explorer Dataset (SE), Census 1840, Digitally transcribed by Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research, edited, verified by Michael Haines. Compiled, edited and verified by Social Explorer.

[6] United States, 1840 Census, Alabama, Franklin County; United States, 1850 Census, Alabama, Franklin County; Alabama, 1850 Alabama State Census, Franklin County, Reuben Copeland and Jo L Griffin.

[7] Albert J. Raboteau, Slave Religion: The ‘Invisible Institution’ in the Antebellum South (New York: Oxford University Press), 211-288.

[8] Anson West, “The Methodists of Alabama in the Crisis of 1844,” A History of Methodism in Alabama, (Methodist Episcopal Church: Nashville, Tennessee 1893): 634-652.

[9] Alabama, 1855 Alabama State Census, Franklin County, Reuben Copeland; United States, 1860 Census, Slave Schedules, Alabama, Franklin County; United States, 1860 Census, Agriculture Schedules, Alabama, Franklin County, Reuben Copeland.

[10] “Minutes of the first annual Conference,” 843-844.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.