Clark, Lucy

Biography

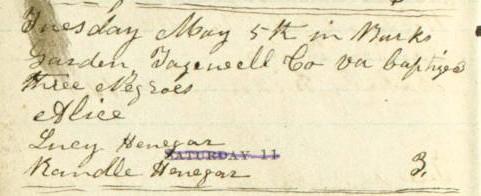

Lucy Clark, her husband Randall, and at least one of their children joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1868 and 1869, when Lucy was approximately thirty-four years old.[1] Elder Henry Green Boyle, the Latter-day Saint missionary who baptized her, wrote of her baptism in his diary, “Today we baptized three negroes. After we baptized, we held a meeting. These negroes are the best in this county. They are the most respectable negroes here. We confirmed them at the water’s edge. I go to Thomas Henninger’s and stay all night.” Elder Boyle later added an entry to his journal listing the names of the three “negroes” he baptized that day which included Lucy and Randall, both bearing the last name of their former enslaver, “Henegar” (more commonly Heninger).[2] Following the Civil War, Lucy and Randall adopted “Clark” as their last name but surviving evidence makes it clear that they are the couple who Boyle baptized.

Much of Lucy’s life before her baptism remains unknown. Her birth year, 1834, is listed on her death record in Virginia’s death registry.[3] The 1870 census, the first time that formerly enslaved people were listed by name, tells us that she was married to Randall Clark but does not specify the year that they wed.[4] Other sources offer additional clues and suggest that her fate as an enslaved woman was tied to that of Randall’s. Two generations of the Heninger family enslaved Randall in Burke’s Garden, an unincorporated area of Tazewell County, Virginia. He was first enslaved to William Heninger, who then left Randall in his 1841 will to his son Thomas Heninger.[5] It is possible that Lucy was enslaved nearby and that Thomas Heninger purchased her sometime thereafter, once she and Randall had married. In fact, according to Heninger family tradition, “a negro man was left to [Thomas] by his parents while the negro’s wife belonged to some other plantation owner, so Thomas bought the Negro’s wife…so she could be with her husband…and they raised a family while they were working on his plantation.”[6]

This story likely refers to Randall and Lucy because it matches what is known of their circumstances. Randall was bequeathed to Thomas in the 1841 will and there was no one named Lucy among the Heningers other enslaved workers. Additionally, Lucy and Randall later lived together as husband and wife and it appears that they and their children remained together while enslaved to the Heningers.[7]

After the Civil War and Emancipation, the Clark family remained near the Heninger family in Clear Fork, as noted in the 1870 census. According to the 1870 and 1880 censuses, Lucy never learned to read or write. She had at least eight children, most likely five of those were born into slavery. One of her sons died in infancy, in 1866.[8]

Henry Green Boyle baptized and confirmed Lucy on 5 May 1868. Lucy had likely been exposed to the Latter-day Saint gospel before she met Elder Boyle that year. Jedediah M. Grant, a Latter-day Saint missionary, had baptized Ann Heninger in 1842, and a Latter-day Saint branch or small congregation was established in Burke’s Garden at that time. Missionaries were frequent visitors to the area and occasionally stayed in the Heninger home.[9] It is not clear what finally prompted Lucy to convert, but the fact that she made the decision to be baptized within three years of receiving her freedom following the Civil War speaks to the value that she placed on religious agency.

After her baptism, Lucy and her family remained in Clear Fork Township in Burke’s Garden but her level of activity in the church is unknown. Even still, Elder Boyle baptized her son Charles A. Clark in 1869, one year after Lucy and Randall, which suggests that she likely continued to practice the Latter-day Saint faith and was intent on passing it on to her children.[10]

While some church members remained in the area during and after the Civil War, most began to gather with the larger body of Latter-day Saints in the Mountain West. This included Thomas and Ann Heninger. In 1870 they began selling off their properties.[11] Heninger family history claims that Thomas “provided for his [former] slaves” before leaving Virginia.[12] Terms of the Heninger land transfer are unknown, but it is possible that Heninger did remember the Clarks before he left for Utah. Lucy’s husband Randall is enumerated as a landowner in the 1880 United States Agricultural Census. The family owned fifteen acres of tilled land, sixty-five acres of woodland, and some farm animals, including a cow, sheep, and poultry. The farm produced grains, sugar, molasses, and wood products from the woodlands.[13]

Lucy died of a fever on 16 July 1884 in Mud Fork, another area of Tazewell County. She was around fifty years old at her passing.[14] During her lifetime, her children and grandchildren remained nearby, living in Tazewell County, and when her husband died ten years later, the couple’s children inherited over thirty-five acres of land.[15]

Although the archival record reveals little of Lucy’s life and religious convictions, her choice to join the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the inheritance that she and her husband left to their family make it clear that faith and family devotion anchored her life.

By Shannon Miller

[1] Virginia, State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death and Burials, 1853-1912, Tazewell County, 1884, Lucy Clark, Virginia State Archives, Richmond, Virginia. Lucy’s birth year is taken from the Death and Burial register.

[2] Henry Green Boyle, diary, vol. 5, 1867-1868, 42, MSS 156, L Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah. Boyle, diary, vol. 5, 4, MSS 156. Family trees use the spelling Heninger, while early records spelled the last name in a variety of ways.

[3] Virginia, State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death and Burials, 1853-1912, Tazewell County, Lucy Clark.

[4] United States, 1870 Census, Virginia, Tazewell County, Clearfork Township.

[5] William Heninger, Virginia, Circuit Court General Indexes to Wills, Tazewell County, Will Book, No 2, 1832-1850, 293, 1 April 1841.

[6] Ina Jones and Janice Williams, “The Story of Thomas Heninger,” Thomas Heninger (KWJ5-V5C), Familysearch.org.

[7] United States, 1860 Census, Slave Schedules, Virginia, Tazewell County. The ages of the enslaved individuals are approximate matches with those listed in Randall and Lucy Clark’s household in the 1870 Census.

[8] United States, 1870 Census, Virginia, Tazewell County, Clearfork Township; United States, 1880 Census, Virginia, Tazewell County, Clearfork.

[9] On the organization of a Latter-day Saint branch at Burke’s Garden, see “Protracted Meeting and Conference,” Times and Seasons (Nauvoo, Illinois) 1 January 1843, 63 and on Ann Heninger’s baptism see Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Ogden 2nd Ward, CR 375 8, box 4892, folder 1, image 73, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[10] Henry Green Boyle papers, 1824-1908, vol. 06, 1869, 78; Sarah Day, “Charles A. Clark,” Century of Black Mormons.

[11] Virginia, Tazewell County Court, Deed Book 15, 1872-1876, 177, 441, Virginia State Library, Richmond, Virginia.

[12] Jones and Williams, “The Story of Thomas Heninger.”

[13] United States, 1880 Census, Agricultural Schedules, Virginia, Tazewell County, Clearfork Township.

[14] Virginia, State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death and Burials, 1853-1912, Tazewell County.

[15] Virginia, Tazewell County, Will Book Vol. 6, 28 June 1888 - 16 April 1895, 498, Randolph Clark, Virginia, Circuit Court, Tazewell County.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.