Copeland, Lewis

Biography

Lewis Copeland was an enslaved man when he joined the Academy Branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. This branch, also known as the Sulphur Wells Academy Branch, met in the northeastern part of Henry County, Tennessee near the Big Sandy River.[1]

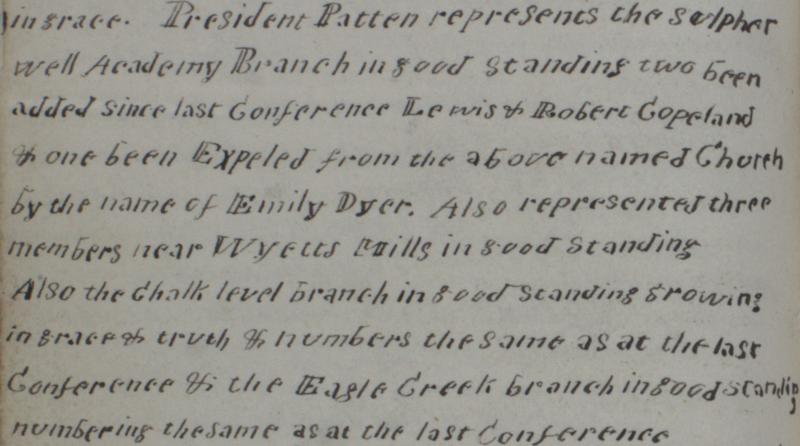

On September 2, 1836, Wilford Woodruff, a missionary and future president of the Church, recorded notes of a conference of the Tennessee and Kentucky branches. In doing so he indicated that two people had “been added since last conference Lewis & Robert Copeland,” who were the newest members of the Academy Branch.[2] Although Woodruff failed to record the precise date of Lewis and Robert’s baptisms, his journal does offer a date range. The previous branch conference met on May 28 of the same year, indicating that Lewis was baptized sometime between then and September 2, 1836. Woodruff also did not mention Lewis or Robert’s race in his journal, but he did write “coloured” in parentheses after their names in a separate notebook in which he listed all members of the Tennessee Conference branches.[3] Woodruff did not indicate if they were enslaved but additional evidence suggests that they were.

The legal situation alone in Tennessee in the 1830s indicates that Robert and Lewis were likely enslaved. Because of the 1831 Nat Turner rebellion in Virginia, the Tennessee legislature made manumission illegal that same year unless the person who was manumitted promised to leave the state. Furthermore, no free Black people could legally immigrate to Tennessee.[4] Likely as a result of such laws, there were only 23 free Black men between the ages of 10 and 99 in Henry County in the 1830 US Federal Census, and only 10 in the 1840 census. None of those free Black men in either census were named Lewis or Robert Copeland or even carried the Copeland surname.

However, the surname that Woodruff recorded for Robert and Lewis points to Solomon Copeland as their enslaver. Copeland was a wealthy landowner and politician who was friendly to the Church’s representatives. According to Woodruff’s journal as well as that of fellow missionary Abraham O. Smoot, they and other representatives often visited and stayed with Copeland while they preached in the region. The friendship began in April 1835 when Woodruff and others participated in healing Copeland’s wife, Sarah.[5] Woodruff also listed Sarah Copeland as a baptized member of the Academy Branch, which further strengthens the connection.[6]

Census records offer additional evidence. Solomon Copeland enslaved five people in 1830.[7] Only two were males, both under the age of ten. Copeland’s tax record from 1836 also indicated that he enslaved five people, all of whom were between 12 and 60 years old and that he owned 500 acres of land.[8] This does not include the children he enslaved, as evidenced by a bill of sale dated September 1838 for Joshua, who was sixteen, Lucy who was eight, and Susan who was seven.[9] By 1840, Copeland enslaved eleven people, including three men between 10 and 24.[10] According to the tax records of 1836, no other residents surnamed Copeland in Henry County, Tennessee enslaved people. The preponderance of evidence thus indicates that Lewis and Robert were young men enslaved to Solomon Copeland at the time of their baptisms.

Circumstantial evidence also suggests that Lewis and Robert were baptized of their own accord. Sarah Copeland was the only member of the Copeland family to be baptized, an indication that there was likely no pressure from Solomon to be baptized into a faith he did not join. Furthermore, of the five to ten people who Copeland enslaved in the 1830s, none of them appear in Woodruff’s membership record or journal besides Robert and Lewis. The Copelands, in other words, did not require all of their enslaved people to convert, but offered them that option. The fact that Lewis and Robert were baptized independently of Sarah also demonstrates a level of choice on their part.[11]

Lewis and Robert had nothing to gain by joining the Church except the gospel as taught by the Latter-day Saints. No other known Black people joined the Sulphur Academy Branch. Even still, racism would have likely distorted their relationship with other Latter-day Saints who countenanced slavery and harbored feelings of white superiority. On top of their status as an enslaved racial minority within their branch, they converted to a suspect minority religion. Thus their experiences in the branch may have also included discrimination and opposition aimed at all Latter-day Saints in the region. Missionary journals from the period indicate that local ministers regularly opposed “the Mormons” and formed mobs against them and their converts.[12]

After Woodruff’s membership list, no other record mentions Robert or Lewis again. Though allowed to join the Church, Robert and Lewis’s status as enslaved men meant that they had no power to continue to worship in the Church if their enslavers left the faith or if their enslavers sold them to other people.

Solomon Copeland died sometime between August 1843 and July 1845.[13] Woodruff at least believed Copland was still alive when he wrote him a letter on March 19, 1844, in which he invited Copeland to serve as Joseph Smith’s vice-presidential candidate as Smith campaigned for the U.S. presidency. Woodruff likely recalled Copeland from his missionary service in Tennessee and viewed him as wealthy, politically sophisticated, and friendly to the Latter-day Saints. There is no indication that Copeland received Woodruff’s letter or what he may have thought of Smith’s anti-slavery presidential platform. Copeland did not respond to Woodruff and may have been dead by that point anyway.[14]

After Copeland’s death, the historical record suggests that Sarah likely sold Robert and Lewis, fellow members of her Latter-day Saint congregation. Two women named Sarah Copeland who match the demographics of Solomon’s wife appear in the 1850 census. One had no slaves and the other enslaved only female adults and some children. Furthermore, none of Solomon and Sarah’s children appear as enslavers in the slave schedules. After being sold, Robert and Lewis would probably not have retained the Copeland last name but would have been known by the names of their new enslavers. If they lived to be emancipated, they may have used surnames of their choosing after that.[15]

By Ami Chopine

Primary Sources

Patten, David Wyman. David W. Patten journal, MS 603. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Smoot, Abraham O. Vol. 1, 1836-1846. MSS 896. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Harold B. Lee Library. Brigham Young University.

Tennessee, U.S. Early Tax List Records, 1783-1895. Henry County, 1836. Entry for Solomon Copeland.

Tennessee. Wills and Probate Records, 1779-2008. Tennessee County. District and Probate Courts.

United States. 1830 Census. Tennessee, Henry County.

United States. 1840 Census. Tennessee, Henry County.

United States. 1850 Census. Tennessee, Henry County

Wilford Woodruff journal, 1833 December-1838 January. MS 1352. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Woodruff, Wilford. Letter, Nauvoo, Illinois to Solomon Copeland, Henry County, Tennessee, March 19, 1844. Joseph Smith's office papers, 1835-1844. MS 21600, box 1, folder 4, image 1-4. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Woodruff, Wilford. Membership Record Book, 1835. Wilford Woodruff Collection. MS 5506, box 2, folder 6. Church History Library. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Secondary Sources

Collier, Melvin. “I Ain’t Taking Massa’s Name.” Roots Revealed: Viewing African American History Through a Genealogical Lens. https://rootsrevealed.com/2020/10/25/i-aint-taking-massas-name/

Crow, Bruce. “Academy Tennessee Branch.” Amateur Mormon Historian. 27 April, 2015.

England, J. Merton. “The Free Negro in Ante-Bellum Tennessee.” The Journal of Southern History. Vol. 9, No. 1 (Feb., 1943): 37-58.

Gates, Henry Lewis Jr., and Meaghan E.H. Siekman. “Tracing Your Roots: Were Slave’s Surnames Like Brands?” The Root. June 16, 2017.

McBride, Robert M., and Dan M. Robison. Biographical Directory of the Tennessee General Assembly. Volume 1, 1796-1861. Nashville, TN: Tennessee State Library and Archives and the Tennessee Historical Commission, 1975.

McBride, Spencer W. Joseph Smith for President: The Prophet, the Assassins, and the Fight for American Religious Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Raboteau, Albert J. Slave Religion The "Invisible Institution" in the Antebellum South. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

Sainsbury, Derek R. Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries. Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 2020.

[1] Bruce Crow, “Academy Tennessee Branch,” Amateur Mormon Historian. April 27, 2015.

[2] Wilford Woodruff journal, 1833 December-1838 January, MS 1352, box 1, folder 1, image 101, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] Wilford Woodruff, Membership Record Book, 1835, Wilford Woodruff Collection, MS 5506, box 2, folder 6, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. Woodruff Listed Lewis and Robert Copeland in the Academy, Tennessee Branch with the word “Coloured” written next to their names.

[4] J. Merton England, "The Free Negro in Ante-Bellum Tennessee," The Journal of Southern History Vol. 9, No. 1 (Feb., 1943): 37-58.

[5] Woodruff journal, 1833 December-1838 January, image 55; Smoot, A. O. vol. 1, 1836-1846, MSS 896, pp. 41-42, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[6] Wilford Woodruff, Membership Record Book.

[7] United States, 1830 Census, Tennessee, Henry County.

[8] Tennessee, U.S., Early Tax List Records, 1783-1895, Henry County, 1836, Entry for Solomon Copeland.

[9] Slave Bill of Sale, Circuit Court records for Henry County, Tennessee, 1816-1850, File Ci6-188, image 54, microfilm 1358305, Family History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[10] United States, 1840 Census, Tennessee, Henry County.

[11] Wilford Woodruff, Membership Record Book, 1835, Wilford Woodruff Collection, MS 5506, Box 2, fd 6, Church History Library.

[12] See Woodruff Journal, 1833 December-1838 January; Smoot vol. 1; and Patten, David Wyman 1800-1838, journal.

[13] Will Books, Vol A-F, 1822-1844,Tennessee, Wills and Probate Records, 1779-2008, Tennessee County, District and Probate Courts; Robert M. McBride and Dan M. Robison, Biographical Directory of the Tennessee General Assembly, Volume 1, 1796-1861 (Nashville, TN: Tennessee State Library and Archives and the Tennessee Historical Commission, 1975), 166-167. See also Solomon Copeland Biography, Joseph Smith Papers, https://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/solomon-copeland

[14] Wilford Woodruff, Nauvoo, Illinois to Solomon Copeland, Henry County, Tennessee, March 19, 1844, Joseph Smith's office papers, 1835-1844, MS 21600, box 1, folder 4, images 1-4, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. For additional context on Joseph Smith’s run for the presidency and his effort to reach out to Copeland see, Derek R. Sainsbury, Storming the Nation: The Unknown Contributions of Joseph Smith’s Political Missionaries (Provo, Utah: Religious Studies Center, 2020), 43, and Spencer W. McBride, Joseph Smith for President: The Prophet, the Assassins, and the Fight for American Religious Freedom (New York: Oxford University Press, 2021), 150-51.

[15] Henry Lewis Gates Jr., and Meaghan E.H. Siekman, “Tracing Your Roots: Were Slave’s Surnames Like Brands?” The Root, June 16, 2017; Melvin Collier, “I Ain’t Taking Massa’s Name.” Roots Revealed: Viewing African American History Through a Genealogical Lens, October 25, 2020.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.