Evans, Annis Bell Lucas

Biography

Annis Bell Lucas Evans was one of eight Black Latter-day Saints baptized for their deceased family and friends in the Endowment House in Salt Lake City, Utah, on September 3, 1875. Despite the prejudices African American women faced at that time, Annis’s life reveals a woman who forged her own religious path. Her faith in the face of adversity paved the way for her posterity to make their own contributions to building inclusive communities.

Annis Bell Lucas was born in Purdy, Tennessee, in about 1853.[1] At that time, Purdy was the county seat of McNairy County, in the southwestern portion of the state, along the border with Mississippi. Farmers in McNairy mainly produced cotton and corn and relied heavily on enslaved labor.[2] Annis was likely born into slavery and numbered among the 1,900 enslaved individuals in McNairy County in 1860.[3]

Divided loyalties caused Tennessee to be the last state in the Confederacy to secede from the Union in the spring of 1861, when Annis was only about eight years old. Western Tennessee overwhelmingly supported secession while the eastern portion of the state preferred to remain within the Union. This divide caused conflict and violence within communities and among neighbors.[4]Although located in western Tennessee, McNairy County had become as equally divided as the state. While a handful of the districts in the county's northern half remained loyal to the Union, the districts in the southern half supported the Confederacy.[5] Living in Purdy, Annis and her family would have found themselves in a community that supported the Confederacy but surrounded by neighboring cities that supported the Union.[6]

As the Civil War began, it is impossible to know how Annis, as a child, may have experienced the conflict. Tennessee’s strategic location made it a primary target of the Union army throughout the war. The Union army occupied western Tennessee by early 1862 and implemented military rule. The resulting harsh policies prompted some occupied citizens to resort to hostilities and defiance.[7]

As the Union army entered western Tennessee in 1862, crowds of poorly dressed and hungry fugitives from slavery surrounded them. Annis may have been among the large number of enslaved workers who fled from their enslavers at the arrival of northern troops. Because the Confederacy forced enslaved people to provide labor for the Confederate Army and Confederate sympathizers, the Union viewed the fugitives from slavery as property of the Confederates and thus considered them contraband. In response, the Union army established what came to be called contraband camps, to provide shelter, food, education, and medical services for the fugitive slaves. Around 20,000 men from these contraband camps were conscripted into military service and formed some of the U.S. Colored Troops within the Union army. These regiments of Black men provided the necessary labor to maintain the Union occupation of Tennessee.[8]

Meanwhile, farther west, Kansas became a free state after years of intense violence and conflict. It entered the Union on January 29, 1861.[9] Thereafter Kansas became a place that symbolized freedom, a notion that prompted many formerly enslaved people to flee there during and after the Civil War.[10] Perhaps this is how Annis eventually crossed paths with William Evans, whom she married in Junction City, Kansas, on March 12, 1868, three years after the Civil War ended. Annis was about 15 years old at the time and William was 23.[11] William was likely also born into slavery in Richmond, Virginia, in about 1845.[12] While living in Kansas, Annis gave birth to their first child, Carrie, by the end of 1868.[13]

Following the end of the Civil War, the search for employment and the hope of greater opportunity enticed thousands of African American men to cities and a growing urban economy in the West.[14] William followed this path and by 1870 he and Annis had moved their small family to Denver, in Colorado Territory, where he worked as a cook in a hotel.[15]

With the arrival of the railroad in 1869 and the advent of new technology for more efficient mineral extraction, the mining industry in Utah grew significantly.[16] This growth prompted Annis and William to follow financial opportunities westward from Colorado to Utah Territory where William obtained employment as a cook for a mining company.[17] Annis gave birth to their second child, William Jr., in 1872, in Utah.[18]

William lived at least part of the year in the Granite Precinct mining town while Annis maintained their residence within the Eighth Ward boundaries in Salt Lake City with their two small children.[19] It would have been difficult at times for a nineteen-year-old woman with a baby and a small child to live without her husband's assistance and companionship. Annis would have had to rely on help from those within her community. This is likely when Annis met Susan Leggroan, Amanda Chambers, Jane Manning James, and Mary Ann Perkins James, four other African American women who lived within the Salt Lake Eighth Ward boundaries.[20]

These women would have experienced similar hardships in their lives, making them invaluable sources of support and strength for one another. The relationships Annis created with them likely became important to her, especially as the African American population in Salt Lake City was below one percent at the time.[21] One of these women likely introduced Annis to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The Church teaches its members that it is their responsibility to share the gospel message with others. At least one of them would have felt a desire, or at least an obligation, to invite Annis to learn about the Latter-day Saint gospel and participate in meetings and activities.

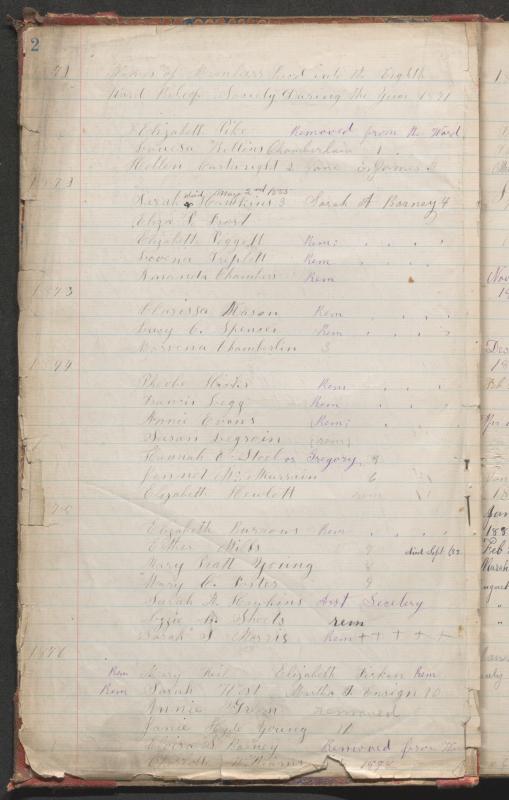

Although no baptismal record survives for Annis, or for any of her family, she likely joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints sometime in 1873.[22] Her children, Carrie and William Jr., received blessings on January 1, 1874, by J. Brockbank.[23] And on February 5, 1874, the Eighth Ward Relief Society welcomed and voted Annis into the society, along with Susan Leggroan.[24]

In April of 1875, Annis gave birth to her and William’s third child, Esther.[25] Five months later, on September 3, 1875, Annis attended the Endowment House to participate in proxy baptisms alongside seven other African American Latter-day Saints from the Eighth Ward. Annis acted as proxy for three of her deceased sisters and two friends. At the same time, Amanda Chambers’ husband, Samuel, acted as proxy for three of Annis’s male relatives.[26] Annis’s eagerness to help her deceased family members receive baptism offers a peek into who was on her mind as she considered the eternities. Her desire to have her own children blessed in the church as they were born also shows a deep and abiding love for her family and a commitment to her newly adopted faith.

William did not participate in the proxy baptisms at the Endowment House, which might indicate that he was living in the mining camp at the time and could not attend. More likely, it might mean that William was not a Latter-day Saint and that Annis had converted on her own. Perhaps William had no desire to join a religion that offered priesthood and temple rituals to white men while denying them to Black men. In either case, Annis was surrounded by fellow Black Latter-day Saints at the baptismal font in the Endowment House on that singular day in 1875, but William was not there.

Sometime between 1875 and 1880, the Evans family moved away from the Eighth Ward. By June of 1880, another daughter, Belle, had been added to the family, and William’s work with the mining company slowed.[27] Likely motivated by the inconsistency of the mining industry and the separation from his family, William eventually found employment nearer to home where he worked as a cook for two prominent hotels in the city.[28] Annis gave birth to her last child, Mercy, in 1885 while the family still resided in Salt Lake.[29]

Annis likely stopped participating in church service and activities during this time. Annis’s name was recorded in an additional Eighth Ward Relief Society record with an undated notation stating that she “removed from the ward.”[30] She did not accept rebaptism when Susan Leggroan and other Black Latter-day Saints did in 1876, suggesting that she had moved out of the Eighth Ward by that point or opted not to get rebaptized. When Annis and her family moved into the Thirteenth Ward boundaries sometime between 1875 and 1880, there are no records indicating a transfer of her membership to the new ward.

Brigham Young and other Latter-day Saint leaders preached retrenchment and a reassertion of economic communalism known as the United Order during this time. As a part of this movement, members were encouraged to distance themselves from those considered “gentiles,” or outsiders. This may have been uncomfortable for Annis because her husband was likely not a Latter-day Saint and he worked in the hotel industry where he associated on a daily basis with individuals who Latter-day Saints considered to be “gentiles.” Polygamy was also a contentious issue in national politics which led to division between Latter-day Saints and outsiders as well as division within the Latter-day Saint community. Some Latter-day Saints did not find polygamy to be an inspired and divine law and chose to leave the church.[31] It is impossible to know why Annis may have stepped away from the faith that had inspired her in 1875 with the possibility of reaching beyond mortality to offer her deceased relatives and friends saving rites. Discomfort over polygamy may have prompted Annis’s departure from the faith or uneasiness over retrenchment, or perhaps it was the hardening of racial policies that denied people of Black African ancestry the same blessings that others were promised.[32] Any number of possibilities, combined with the departure of Susan Leggroan, Amanda Chambers, and Mary Ann Perkins James from Salt Lake, might have left Annis feeling disconnected and dissatisfied with the church she had joined.[33] In any case, her faith journey would soon take her in a different direction after she and her family moved from Utah Territory.

In 1888, Annis and William’s oldest child, Carrie, eloped to Glenwood Springs, Colorado, with an African American Soldier from the Ninth Cavalry stationed at Fort Duchesne.[34] This elopement may have added to a sense of disconnection from the Latter-day Saints within her community, especially if they frowned upon it. Carrie divorced her husband five years later and moved to Denver, Colorado.[35]

Sometime between 1892 and 1894, the rest of the Evans family relocated to Denver as well.[36] The loss of Annis’s support system in Salt Lake, as well as a national and local racial climate that increasingly favored segregationist principles, may have factored into the decision. The family’s desire to be near their daughter during a difficult time, no doubt ultimately prompted the move.

Sadly, Annis and William’s only son, William Evans, Jr., died in 1894 when he was only about twenty years old and was buried in an unmarked grave in the Fairmount Cemetery in Denver.[37] Around this time, Annis converted to the Seventh-day Adventist Church in her new hometown.[38]

The similarities between the teachings of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the Seventh-day Adventists perhaps offer insights into what Annis found important to her faith. Among the similarities, two stand out: the resurrection of the dead after the literal second coming of Jesus Christ and the sacredness of families. Annis had lost many of her loved ones by the time she was a young adult. It would have been of great comfort to her to know that she would see those that she had lost in the eternities and be able to live with them in a world without hatred and violence.

As a Black woman, she likely dealt with instances of prejudice, discrimination, and exclusion as a member of the Seventh-day Adventist Church, like she would have in broader American society during the height of racial segregation. Still, the limitations that existed for Black people within the Latter-day Saint faith did not exist within the Adventist faith that she now embraced.

Annis took full advantage of the opportunities that came along with her new faith. From its beginning, the Seventh-day Adventist Church emphasized the importance of education and improving and caring for oneself physically, mentally, and spiritually.[39] In 1895, the Adventist Church helped to establish the Boulder, Colorado, Sanitarium a resort and health spa grounded in healthy diets and outdoor recreation. Annis’s daughter, Esther, attended an affiliated nursing program and was one of eleven students—and the only African American student—in the first graduating class, in 1898.[40]

Annis’s younger daughters, Belle and Mercy, attended the Seventh-day Adventist college in Lincoln, Nebraska. While at school, they lived in a boarding house with other students. Belle graduated in 1900, and Mercy graduated in 1901.[41] During the time her daughters attended school in Nebraska, Annis suffered a brain injury from an accident. Esther likely used her nursing skills to help support the family and care for her ailing mother. Two years after her accident, Annis died on May 8, 1902, in Denver, Colorado, due to an illness brought on by the trauma to her brain. Annis was buried on May 11, 1902, in Fairmount Cemetery in Denver, in an unmarked grave.[42]

Annis’s legacy, nonetheless, lived on following her death, especially in the principles of hard work and the value of education that she had instilled in her children. After her death, William moved with Belle and Mercy to Ogden, Utah where he worked as a cook, and Mercy continued her education.[43] Following the move, Esther and Belle both married.[44] Unfortunately, Mercy died at the age of eighteen and was buried in the Mountain View Cemetery in Ogden, in an unmarked grave.[45]

Sadly, William and Esther’s family line may have died out relatively quickly. Esther had one child, June Arcene, who died at the age of one from Typhoid Fever.[46] The only possibility of any existing posterity for Annis and William is through the child that Belle and her husband adopted. This baby was found abandoned on the steps of a Home for the Aged and Infirm Colored People. Belle named her after her sister, Esther. She lived to adulthood and eventually married, but she disappears from public records after 1966, with no apparent children who survived her.[47]

Even still, Annis’s legacy survives in the contributions her children made to their respective communities. Belle and Esther worked alongside their husbands within their church congregations and within the larger African American community to promote progress and industry. Both women remained faithful members of the Seventh-day Adventist Church. They passed away within four years of each other. Esther was buried in Idaho, and Belle in California.[48]

Despite the harsh realities that constrained Black people in Jim Crow America, many mothers like Annis raised their daughters to believe that they could do and become anything and taught them to live as if that were true. Community was a crucial factor in instilling the self-confidence and faith that these girls needed to not only achieve success in their own lives but also contribute to the successes of those around them.[49]

Despite being drawn to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and being one of only a handful of Black Saints in the nineteenth century to participate in proxy baptismal rituals for deceased relatives and friends, Annis chose a different path—a faith that valued her perspective as a Black person. She sought and found opportunities within the Seventh-day Adventist community that allowed her children to thrive and succeed. The difficult and intentional choices Annis made paved the way for the success of her daughters and instilled within them a legacy of faith and perseverance.

By Jackie Pruett

[1] Utah, State Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Records & Statistics, Utah Death Certificates, Series No. 81448, Mercedes Cornelia Evans; Kansas, Davis County, Marriages, 1811-1911, Wm Evans and Anna Lucas, 12 March 1868.

[2] Marcus Joseph Wright, Reminiscences of the Early Settlement and Early Settlers of McNairy County, Tennessee. (Washington D.C.: Commercial Pub. Co., 1882), 8; Bill Wagoner, “McNairy County,” Tennessee Historical Society, 1 March 2018, accessed 12 June 2025.

[3] United States, “Population of the United States in 1860: Tennessee,” United States Census Bureau, 466.

[4] Larry H. Whiteaker, “Civil War,” Tennessee Historical Society, 1 March 2018, accessed 10 June 2025.

[5] Wagoner, “McNairy County.”

[6] Charles L. Lufkin, “Divided Loyalties: Sectionalism in Civil War McNairy County, Tennessee,” Tennessee Historical Quarterly 47, no. 3 (1988): 169–77.

[7] Stephen V. Ash, “Civil War Occupation,” Tennessee Historical Society, 6 March 2018, accessed 12 June 2025.

[8] Ash, “Civil War Occupation.”

[9] Margaret Hu, 2024. "Follow the Bloody Brick Road: Bleeding Kansas and the Emancipation Proclamation," William and Mary Bill of Rights Journal 33 (2): 569-589.

[10] Quintard Taylor, “African American Men in the American West, 1528-1990,” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 569 (2000): 105.

[11] Kansas, Davis County, Marriages, 1811-1911, Wm Evans and Anna Lucas, 12 March 1868.

[12] Utah, State Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Records & Statistics, Utah Death Certificates, Series No. 81448, Mercedes Cornelia Evans; Kansas, Davis County, Marriages, 1811-1911, Wm Evans and Anna Lucas, 12 March 1868.

[13] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eighth Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, image 135, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah (hereafter CHL); Carrie’s birthplace is listed as Salt Lake on the church record, but all other records list her birthplace as Kansas.

[14] Taylor, “African American Men in the American West, 1528-1990,” 108–09.

[15] United States, 1870 Census, Colorado Territory, Arapahoe County, Denver.

[16] Colleen Whitley, From the Ground Up: A History of Mining in Utah (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2006).

[17] United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Granite Precinct.

[18] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eighth Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, image 73, CHL.

[19] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eighth Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, images 73 and 135, CHL.

[20] Tonya Reiter, “Black Saviors on Mount Zion: Proxy Baptisms and Latter-day Saints of African Descent,” Journal of Mormon History 43, no. 4 (October 2017): 100-123.

[21] U.S. Census Bureau, “1870 Census: Vol. I. The statistics of the population of the United States,” accessed 25 June 2025.

[22] Annis was voted into the Relief Society at the same time as Susan Leggroan, possibly indicating that she joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at or around the same time as Susan who was baptized on June 5,1873; “Correspondence,” The Elevator (San Francisco, California), 14 June 1873.

[23] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eighth Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, images 73 and 135, CHL.

[24] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Eighth Ward Relief Society Minutes and Records, LR 2525 14, image 136, CHL.

[25] Idaho, State Department of Public Welfare, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, District No. 1006, State File No. 57562, Ester Lund; Esther’s birth year changes across records with 1875 being the best estimate. Age discrepancies were not unusual for this time period, but were especially prevalent among records for African Americans.

[26] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Colored Brethren and Sisters, Endowment House, Salt Lake City, Sept. 3, 1875,” microfilm 255,498, CHL.

[27] United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Granite Precinct.

[28] Salt Lake City, Utah, Directories, 1890, 1822-1995; Salt Lake City, Utah, Directories, 1892, 1822-1995.

[29] Utah, State Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Records & Statistics, Utah Death Certificates, Series No. 81448, Mercedes Cornelia Evans.

[30] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Eighth Ward Relief Society Minutes and Records, LR 2525 14, image 6, CHL.

[31] See W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), Chapter 6 to learn more about national perceptions regarding polygamy. Relief Society and other minutes and accounts found within church records for this time show how polygamy was openly discussed in meetings and members were encouraged to support those who practiced it and not speak against it. The records also reveal some of those who openly disagreed with the practice and chose to leave the Church as a matter of principle.

[32] See Reeve, Religion of a Different Color, Chapter 7, to learn more about the Church’s adoption of the “one drop” rule and the evolution and implementation of the Church’s racial restrictions.

[33] United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Butler; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Mill Creek; United States, 1900 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Mill Creek.

[34] Colorado, Garfield County, Marriages, 1862-2006, James E. Harris and Carrie E. Evans, 22 April 1888.

[35] Colorado, Divorce Index, 1851-1985, James E. Harris and Carrie E. Harris, 30 March 1893.

[36] Denver, Colorado, Directories, 1894, 1822-1995.

[37] Fairmount Sexton Records Index, 1891-1953, Denver, Colorado, William Evans; William “Willie” Evans, Findagrave.com.

[38] No membership record has been found to indicate the exact date that Annis joined the Seventh-day Adventist Church. She would have joined sometime between her arrival in Denver around 1893 or 1894 and her daughter attending the nursing program at the Boulder Colorado Sanitarium in 1896.

[39] “What do Adventists Believe?,” Seventh-day Adventist Church, accessed June 26, 2025.

[40] Boulder Public Library, “Boulder-Colorado Sanitarium and Hospital School of Nursing Handbook,” A.A. Paddock Collection, BHS 328-145-11c, image 20; General Conference Corporation of Seventh-day Adventists, “An Interesting Letter From Colorado,” Gospel Herald 5, no. 2 (1908), image 2. Accessed 26 June 2025.

[41] General Conference Corporation of Seventh-day Adventists, “Roll Call of Union’s Alumni,” Educational Messenger 17, no. 7 (1921), images 15-16. Accessed 26 June 2025.

[42] General Conference Corporation of Seventh-day Adventists, “Obituary,” Echoes From the Field 12, no. 10 (1902), image 2. Accessed 26 June 2025; Fairmount Sexton Records Index, 1891-1953, Denver, Colorado, Annis Bell Evans; Annis Bell Evans, Findagrave.com.

[43] Ogden, Utah, Directories, 1904, 1822-1995; Mercy was a student at the time of her death according to her death record.

[44] Utah, Salt Lake County, Marriages, 1887-1966, Ernest C. Lunn and Esther Evans, 25 February 1904; Colorado, Mesa County, Marriages, 1862-2006, JW Turner and Belle Evans, 20 September 1905.

[45] Utah, State Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Records & Statistics, Utah Death Certificates, Series No. 81448, Mercedes Cornelia Evans; Mercedes Cornelia Evans, Findagrave.com.

[46] General Conference Corporation of Seventh-day Adventists, “Obituaries,” Review and Herald 86, no. 34 (1909), image 23. Accessed 26 June 2025.

[47] California, Alameda, Probate Records, 1918, Adoption of Beulah Storey, 29 August 1918.

[48] Idaho, State Department of Public Welfare, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, District No. 1006, State File No. 57562, Ester Lund; “Turner,” Oakland Tribune (Oakland, CA), 3 September 1931, 39.

[49] Stephanie J. What a Woman Ought to Be and to Do: Black Professional Women Workers During the Jim Crow Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 10.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.