Fango, Gobo

Biography

Gobo Fango (Xhosa Tribe) was born at the Eastern Cape Colony of South Africa around 1855, after the Eighth Cape Frontier War.[1] European colonization brought violence and starvation to the region. Dutch cattle brought lungsickness which spread among local livestock and decimated many herds. One cheifdom killed 96% of its cattle in response to the epidemic. One Xhosa priestess named Nongqawuse convinced her followers that slaughtering their cattle would cause them to be resurrected twofold and thereby provide more meat and beasts of burden for their people. Her uncle, a convert to the Anglican church, mixed her prophesy with biblical apocolypticism and spread the word. The prophecy failed and when combined with the accumulating pressure of colonization and the cattle epidemic, the resultant famine left thousands of Xhosa struggling to survive. Fango’s mother was one of the starving.[2]

According to later records, Fango’s mother left Gobo with Henry and Ruth Talbot, white property owners in the area, while she went to ask for food. At some point Fango’s mother died and, according to Talbot family tradition, the Talbots “fed [Fango] and cared for him and he was bound to [them] till he was of age to do for himself.[3] The Talbot family later claimed that Fango was like an adopted member of their own family, though the historical record indicates that he was a servant.[4]

The Talbots joined the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1857 in Queenstown, South Africa.[5] No contemporary records suggest that Fango received baptism at that time. He would not have been 8 years old, the requisite age for baptism into the Church. Research of the South African Mission records conducted in the late twentieth century claimed that Fango was baptized, but no documents available to researchers today confirm that claim.[6] In 1992, a team of researchers commissioned by the LDS Church’s Historical Department was unable to verify his membership.[7] There are no records of Fango’s baptism or LDS Church membership in any of the locations in which he lived.

On February 20, 1861, the Talbots and other Latter-day Saints boarded the ship Race Horse from Port Elizabeth, South Africa to Boston, with the final goal of gathering with fellow Saints in Salt Lake City, Utah. The Talbots reportedly planned to leave Fango in South Africa until he was able to convince them to take him with them. If true, this story suggests that the Talbots viewed him as a servant and not as a member of their family.[8] To smuggle Fango aboard the ship, they wrapped him inside a carpet or placed him inside a box in the cargo area.[9] Once the boat was set, several sources suggest that Fango provided entertainment for sailors and took care of the sheep on board the Race Horse.[10]

The Talbots and Fango arrived in the United States at the beginning of the Civil War. Because of prohibitions against transporting enslaved persons (or those that appeared to be enslaved by virtue of their skin color), the Talbots’ kin remembered hearing that Ruth Talbot had to hide Fango under her hoop skirts. Other accounts tell of Fango dressing as a woman with a veil in order to conceal his identity and prevent the Talbots from suspicion for transporting someone believed to be enslaved.[11]

The Talbots traveled west from Boston to Salt Lake City, where they arrived on September 13, 1861. They eventually settled in Kaysville, Utah where Fango reportedly worked for them as a laborer. Fango’s feet froze one year when the Talbots allegedly forced him to herd animals in bare feet. When someone suggested that one of his feet required amputation he said, “He would rather have part of a foot than none at all.” It seems that part of his heel was removed, but that doctors did not amputate his foot at the ankle. Years later, a woman reported that Fango would place wool in his boot so that his foot would fit into it and he could walk.[12] He left the Talbots and worked as a laborer for the Mary Ann Whitesides Hunter family, who lived in Grantsville, Utah, roughly between 1870 and 1880.[13] He was listed as a “servant” (likely employed as such) in the 1880 U.S. Census living in Grantsville.[14]

By the early 1880s he had settled in the Goose Creek Valley of Idaho Territory and worked as a sheepherder. He entered into a business relationship with Walter Matthews and Edward Hunter, the latter being the nephew of the Presiding Bishop of the LDS Church.[15] Fango was known as possessing a “cheerful disposition, quite generous with what he had” and “inoffensive . . . [and] kind to children.”[16]

In 1886, a longstanding conflict between cattlemen and sheepherders resulted in Fango’s death. In that year, cattlemen demanded that all of the sheepherders in Goose Creek leave the valley and its fertile grazing fields. According to a letter published in the Deseret News most sheepherders in the region were Mormon. Cattlemen of other faiths resented the sheepherders lack of consideration in sharing grazing land.[17] In the wake of the mounting tension, a cattleman named Frank Bedke from Woodriver, Idaho sought to force Fango to leave the Valley. Bedke and another man approached Fango on horseback and “accused Fango of trespassing on land reserved for cattle grazing.” Bedke asked Fango to “reason with him,” and then knocked Fango’s firearm away from him, shot him, and reportedly called him a “Black Son of a Bitch;” when Fango did not die immediately Bedke shot him in the body.[18] Badly injured, Fango then walked more than a mile seeking medical assistance.[19]

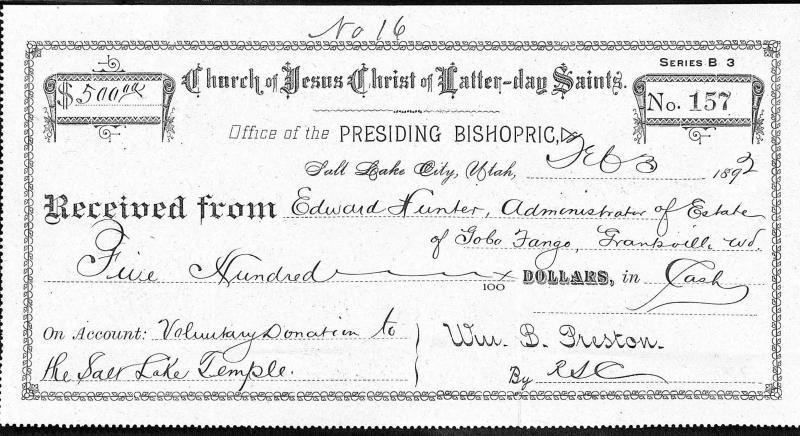

Fango’s wounds did not prevent him from dictating his last will and testament. He left $200 to the “needy poor of Grantsville City, Tooele County, Utah Territory,” as well as several donations of less than $100 to Hunter family members. He also left half of his estate ($500) to the Salt Lake Temple Construction Fund.[20]

Bedke was brought up on murder charges, but the jury did not reach the required unanimous verdict to convict him. In a second trial, the jury acquitted Bedke and claimed he had killed Fango in self-defense.

Fango’s grave is located in the Oakley, Idaho city cemetery. The headstone reads: “Gobo Fango, died February 10, 1886.”[21]

Nearly forty-five years after Fango’s murder, members of the Henry Talbot and Edward Hunter Families searched for evidence of his LDS Church membership. When they could not find any evidence of his baptism and confirmation, Hunter’s daughter and son-in-law, Helen Louisa Hunter Hale and Solomon E. Hale, had his baptism performed by proxy in the Salt Lake City Temple on September 20, 1930.[22] Because Fango was a Black African, he could not be ordained to the priesthood posthumously, which would have made it possible for him to receive other LDS liturgies by proxy. As Louisa Hale, wrote to a historian seeking information on Fango in 1934, “a Negro cannot hold the priesthood. So [performing his posthumous baptism] was all we could do for him. I of course feel that he is more worthy than many that do hold it. I am not the Judge, however.”[23]

By Joseph Stuart

Primary Sources

Claus Karlson Journal. February 1886. In Information Pertaining to the Life and Death of Gobo Fango, 1992. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Fango, Gobo. File, circa 1977-1993. Church History Library. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Forty Years in South Africa.” In Historical Data on the Talbot Family. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah.

Hale, Sol. E. to Kenneth Larsen. August 31, 1934. In Historical Data on the Talbot Family. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah.

Henry J. Talbot Reminiscences of life in South Africa, circa 1910. Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Historical Data on the Talbot Family. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah.

Hunter, J. Austin to Kenneth Larsen, August 7, 1934. In Historical Data on the Talbot Family. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah.

Information Pertaining to the Life and Death of Gobo Fango, 1992. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Larsen, Kenneth. A History of the Talbot Sweetnams. July 15, 1936. Talbot Reunion, Lewiston, Utah, 3rd Ward. In Historical Data on the Talbot Family. L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Brigham Young University. Provo, Utah.

“Oakley Homicide.” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, UT). March 3, 1886.

United States. 1880 Census. Utah Territory, Tooele County, Grantsville.

Utah. Wills and Probate Records, 1800-1985. Utah, County, District and Probate Courts. Probates. Grantsville Donation. Box 1, Folder 32, Image 122. Ancestry.com.

Utah. Wills and Probate Records, 1800-1985. Utah, County, District and Probate Courts. Probates. Inventory of Fango’s Possessions. Box 1, Folder 32, Images 82-86. Ancestry.com.

Utah. Wills and Probate Records, 1800-1985. Utah, County, District and Probate Courts. Probates. Salt Lake City Temple Donation. Box 1, Folder 32, Image 129. Ancestry.com.

Wake, Kiyda Hunter. Notes. In Gobo Fango file, circa 1977-1993. Church History Library, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Secondary Sources

Burton, H. David. “Baptism for the Dead.” Encyclopedia of Mormonism.

Carter, Kate B. Our Pioneer Heritage, 20 vols. Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1958-1977.

“Edward Hunter.” The Joseph Smith Papers.

Fango, Gobo. FindaGrave.com.

Garrett, H. Dean. “The Controversial Death of Gobo Fango,” Utah Historical Quarterly 57, no. 3 (Summer 1989): 264-272.

Hilmo, Tess. “Gobo Fango.” Friend, March 2003.

Hunter, William. Edward Hunter, Faithful Steward. Salt Lake City: Publisher’s Press, 1970.

Makin, A.E. “The Gathering to Zion.” In 1820 Settlers of Salem: Hezekiah Sephton’s Party. Wynberg, South Africa: Juta & Co., 1971.

Peires, J. B. The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-57 . Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989.

[1] For more on the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement, see J. B. Peires, The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-57 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989). Fango’s first name was remembered as Cober, Gober, Geber, Guebber, or Gibber, as well as Gobo by Talbot family members. See Kenneth Larsen, “Historical Data on the Talbot Family,” Provo, Utah, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University (hereafter “Historical Data”). He is listed as Goboac in the LDS Overland Trail Database. See “Duncan, Homer, Report of Elder Homer Duncan’s Mission to England in the years 1860 and 1861,” Mormon Pioneer Overland Trail, accessed June 1, 2018, https://history.lds.org/overlandtravel/sources/89599817708978350840-eng/duncan-homer-report-of-elder-homer-duncan-s-mission-to-england-in-the-years-1860-and-1861?firstName=Gobo&surname=Fango.

[2] Kiyda Hunter Wake Notes in “Gobo Fango file, circa 1977-1993,” Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] “Henry J. Talbot Reminiscences of life in South Africa, circa 1910,” MS 11423, page 13, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[4] Tess Hilmo,“Gobo Fango,” Friend, March 2003. ; “A History of the Talbot Sweetnams,” read by Kenneth Larson on July 15, 1936, at the Talbot Reunion, Lewiston, Utah, 3 rd Ward; “Forty Years in South Africa,” in “History Data”; H. Dean Garrett, “The Controversial Death of Gobo Fango,” Utah Historical Quarterly 57, no. 3 (Summer 1989): 266; “A History of the Talbot Sweetnams,” in “History Data.” The Talbots employed Black Africans when they lived in South Africa.

[5] “Henry J. Talbot Reminiscences of life in South Africa, circa 1910,” page 13, Church History Library.

[6] “Gobo Fango file, circa 1977-1993,” Appendix III, Church History Library.

[7] “Information Pertaining to the Life and Death of Gobo Fango, 1992,” Church History Library.

[8] “Forty Years in South Africa,” in “Historical Data.”

[9] “Miscellaneous Topics,” in “Historical Data.”

[10] “Henry J. Talbot Reminiscences of life in South Africa,” Church History Library; A.E. Makin, “The Gathering to Zion,” in 1820 Settlers of Salem: Hezekiah Sephton’s Party (Wynberg, South Africa: Juta & Co., 1971), 115.

[11] Letter from Mrs. Sol. E. Hale to Kenneth Larsen, August 31, 1934 and “Forty Years in South Africa” in “Historical Data”; Makin, “The Gathering to Zion, 115-116.”

[12] Letter from Mrs. Sol. E. Hale to Kenneth Larsen, August 31, 1934, in “Historical Data.”

[13] Kate B. Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage, (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1958-1977), 8:545; Makin, “The Gathering to Zion,” 117-118; “A History of the Talbot Sweetnams” in “History Data.” A Hunter family member claimed that he “paid for” Fango, but the account is not footnoted and disagrees with several generally agreed upon details of Fango’s death. See William Hunter, Edward Hunter, Faithful Steward (Salt Lake City: Publisher’s Press, 1970), 244.

[14] A white servant was listed as “Gobo Fangs,” in United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Tooele County, Grantsville.

[15] Garrett, “The Controversial Death of Gobo Fango,” 267. See “Edward Hunter,” The Joseph Smith Papers. http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/person/edward-hunter.

[16] Letter from J. Austin Hunter to Kenneth Larsen, August 7, 1934 and Letter from Mrs. Sol. E. Hale to Kenneth Larsen, August 31, 1934, in “Historical Data.”

[17] “Oakley Homicide,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, UT), March 3, 1886.

[18] “Oakley Homicide,” Deseret News; Claus Karlson Journal, February 1886, in “Information pertaining to the life and death of Gobo Fango, 1992,” Church History Library.

[19] Garrett, “The Controversial Death of Gobo Fango,” 267-271.

[20] Edward Hunter donated $500 to the Salt Lake City Temple in 1892 in Fango’s name. It is not clear why there was a delay in the donation process. $200 was donated to the Grantsville, Tooele, Utah Stake and was invested into the town’s co-op. Utah, Wills and Probate Records, 1800-1985, Utah County, District and Probate Courts, Ancestry.com.

[21] “Gobo Fango,” Find a Grave. https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/16585696/gobo-fango.

[22] Solomon Hale was a genealogist and Latter-day Saint temple worker. It is likely that if records existed he could have found them. Letter from Genealogical Society of Utah to Kenneth Larsen, September 1, 1934, in “Historical Data.” See H. David Burton, “Baptism for the Dead,” Encyclopedia of Mormonism. http://eom.byu.edu/index.php/Baptism_for_the_Dead.

[23] Letter from Mrs. Sol. E. Hale to Kenneth Larsen, August 31, 1934 and “Forty Years in South Africa” in “Historical Data.”

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.