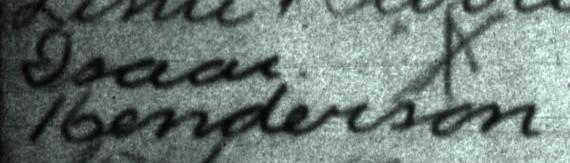

Henderson, Isaac

Biography

Though the details of Isaac Henderson’s life are unclear, contextual evidence suggests that he endured his share of hardships. Similar to many African Americans in the nineteenth century, records regarding his ancestry, childhood, family life, adolescence, and adulthood, are sparce. In fact, only two surviving sources match with any degree of certainty what is known about Isaac. Contextual evidence offers additional clues, but no documents provide a lens into what the world looked like from Isaac’s perspective. Whatever challenges he may have endured and successes he may have celebrated, something prompted Isaac to join a fledgling branch of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Jacksonville, Florida in 1906. He was 76 years old at the time of his conversion and his life’s experiences to that point likely factored into his decision.[1]

Isaac was born on 25 December 1830, less than a decade after Florida, his birthplace, became an official U.S. territory and fifteen years before it became a state.[2] It would be thirty-five years following his birth before the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution emancipated enslaved people nationwide at the end of the Civil War. It is likely that Isaac was born into slavery given that almost 35,000 people lived in Florida Territory in 1830; of that total population, only 844 were free Black people and 15,501 were enslaved.[3] Even if he was born among the free Black population it would not have protected him from hash discrimination and prejudice which was rampant in the antebellum and postbellum South.

The shift in governance, from Spanish to American rule in Florida enshrined an ideology in place that all Black people were inherently lesser beings. As such, the argument went, they were only suitable and useful when serving as slaves.[4] Even if Isaac was born free, his birth would have been a violation of Florida law. By the 1830’s, free Black people were banned from residing in Florida entirely, and those who were set free within the state were taxed a fee of $200 (about $6,600 in 2024) and forced to leave the state within thirty days.[5] Whatever his status, as a child born in St. Augustine, Isaac unknowingly helped to replenish the dwindling Black population of the area as free Black residents from the city had fled not just the state but the entire country and moved primarily to Cuba to preserve their freedom in the wake of the transfer of Florida from Spain to the United States.[6]

It is not until 1885, well into Isaac Henderson’s life, that he first appears in a record that mostly matches what is known from his Latter-day Saint membership entry. The 1885 Florida state census lists Isaac as a farmer who lived in Duval County, Florida, the same county in which he would be baptized twenty-one years later. His household included a wife named Lusy, and two sons and two daughters. Frustratingly, the age listed on the census for Isaac does not match what it should be if he was indeed born in 1830 as indicated on his baptismal record. The census lists him as 43 years old rathar than 55. Such discrepancies are not uncommon in census documents and it is possible Isaac did not know his birthyear, especially if he was born into slavery. If the Isaac Henderson on the 1885 census is the correct Isaac Henderson, it offers the only indication to date that he was married and had children.[7]

On 28 October 1906, Elder James Elias Wellard from Twin Graves, Idaho, baptized Isaac into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at the age of seventy-six. Elder Hugh Lester Geddes from Preston, Idaho then confirmed him on the same day.[8] No records survive to indicate how the missionaries first met Isaac or what attracted him to the Latter-day Saint message. The Latter-day Saint population in Jacksonville was small and only a few branches of the church existed in the state. Mission records do indicate that Isaac was one of eleven people to be baptized in Florida between 20 October and 20 November of that year.[9] Whatever Isaac’s motivation, his decision may have provided him with spiritual support and a sense of community, but it may have also introduced new hardships into an already potentially difficult racial environment.

Isaac joined the LDS Church at the beginning of its incursion into the state of Florida. Some residents of Florida initially resented the Latter-day Saint presence there and considered LDS missionaries as “spiritual carpetbaggers.” Some missionaries reported serious forms of retaliation and abuse while preaching in the South, including being whipped, tarred and feathered, driven from their homes, and even being killed.[10] It is impossible to know how Isaac, as a Black man, experienced this environment or what his worship experience may have been like, but joining a suspect minority religion with its own discriminatory racial policies must have required courage and a sense of conviction. Isaac is the only known Black Latter-day Saint in the state of Florida at the time.[11]

Unfortunately, there is no death record that unambiguously matches what we know about Isaac Henderson. It is impossible to know how long he lived following his baptism or if he remained a Latter-day Saint. Given his long-term residence in Jacksonville, it is likely that he was laid to rest there when he died.

By Wesley Acastre

With research assistance from Kaelyn Kelly

[1] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida Conference, Southern States Mission, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, image 229, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida Conference, Southern States Mission, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, image 229, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah; “1821 - Florida Becomes Part of the United States” P.K. Yonge Library of Florida History, George A. Smathers Libraries, 20 August 2021.

[3] Roland M. Harper, “Ante-Bellum Census Enumerations in Florida,” Florida Historical Quarterly, Vol. 6, no. 1 (1927), 42.

[4] Jane G. Landers, ed., Colonial Plantations and Economy in Florida (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000), 98-120.

[5] Jane G. Landers, Balancing Evil Judiciously: The Proslavery Writings of Zephaniah Kingsley (Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2000).

[6] “African Americans in St. Augustine, 1565-1821,” Castillo de San Marcos National Monument, National Parks Service, October 2023.

[7] State of Florida, 1885 Census, Duval County; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida Conference, Southern States Mission, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, image 229, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[8] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida Conference, Southern States Mission, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, image 229, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[9] Florida Conference general minutes, 1895-1947, vol. 4, 1906-1926, p. 59, LR 2899 11, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[10] Patrick Mason, The Mormon Menace: Violence and Anti-Mormonism in the Postbellum South (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Heather M. Seferovich, “History of the LDS Southern States Mission 1875-1898,” Master’s thesis, (Brigham Young University, 1996), 17-20.

[11] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Florida Conference, Southern States Mission, CR 375 8, box 2189, folder 1, image 229, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.