Howze, Francis Knight

Biography

Francis "Fannie" Knight was born toward the end of the Civil War, the mixed-race child of an enslaved woman and her enslaver. Fannie grew up in a rare interracial enclave in the heart of the Deep South, living among white and Black family members and eventually marrying a white man. Later in life, she converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, perhaps finding spiritual comfort amidst the increasing inequality and violence of the Jim Crow era.

Fannie was the daughter of Rachel Knight, an enslaved woman, and Jesse Davis Knight, her mother’s enslaver.[1] Before the Civil War, Jesse Davis Knight owned a plantation in Jones County, Mississippi where he enslaved at least four people.[2] Sometime around 1860, Jesse Davis’s father, John “Jackie” Knight, bequeathed “a certain negro woman named Rachel” and any future “increase” to Jesse, an acknowledgment of Jesse’s sexual assertions over Rachel.[3]

Jesse Knight enlisted in the Confederacy in 1861. He returned home briefly in 1863 before dying later that year of pneumonia in an Atlanta military hospital.[4] Fannie was born in the spring of 1864 and thus never knew her father.[5] She had three older siblings: Georgann, born in 1856; Edmund, born in 1857; and Jeffrey Early, born in 1860. Jeffrey Early is also believed to be a son of Jesse Davis, however Georgeann and Edmund’s may have been fathered by Rachel’s previous enslaver or a member of that family.[6]

During the Civil War, Rachel secretly aided "the Jones County Scouts," an informal band of Confederate deserters who harassed Confederate supply lines during the last years of the war.[7] Newton Knight, a nephew of Jesse Davis Knight, acted as leader of this regiment and began an affair with Rachel. At the war’s end, when Fannie was just a year old, Rachel moved with her children to Newton Knight’s property to work as a sharecropper.

On his land, Newton Knight continued to father children with both his white wife, Serena, and Fannie's mother Rachel. According to family tradition, the black and white sides of the family lived alongside each other in relative harmony.[8] Fannie would have grown up in these circumstances, working hard to help cultivate cotton as well as subsistence crops. However, on Sundays the Knights held dances and spelling bees and otherwise found time for enjoyment together despite their hardscrabble farm life.[9]

Acceptance of the mixed-race community that developed among the Knight homesteads did not extend into the surrounding county. Jeffrey, Georgeann, and Fannie attempted to attend the local school alongside Newton’s white children. Descendants recall how the teacher flatly refused to instruct the children, saying, “Go home and tell your mother the school doesn’t accept Negroes.”[10] Martha Wheeler, who was enslaved on Jackie Knight’s plantation and continued to live in and around Jones County after emancipation, corroborates this story with her own recollection: Newton Knight “undertook to send several of his negro children to a white school he had been instrumental in building,” she recalled.[11] Knight’s outrage at the dismissal of his children resulted in a “complete break with the whites.”[12] A day later, the school “mysteriously burned to the ground.” Newton and Rachel were each rumored to be the culprit but no evidence ever substantiated such claims.[13] In lieu of formal schooling, Fannie and her siblings learned to read and write from the school materials brought home by their white relatives.[14]

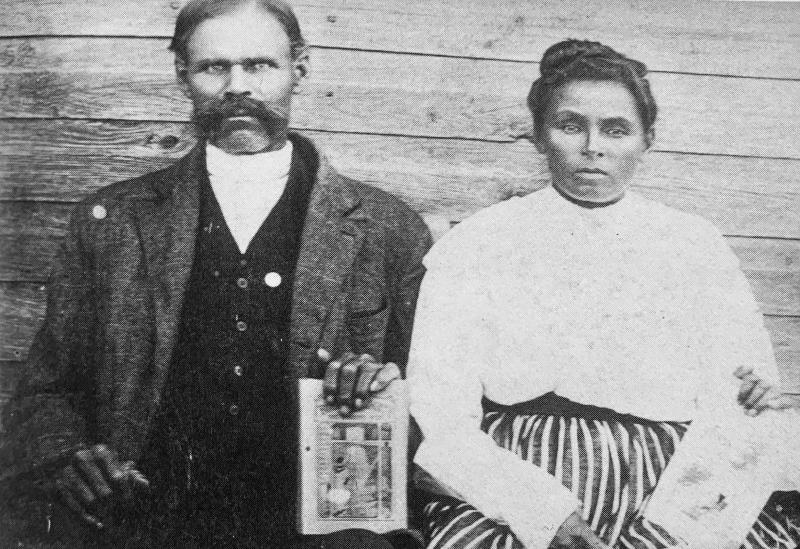

Fannie married George Matthew ‘Mat’ Knight when she was around 16 years old; though the exact date of their marriage is unknown, it was likely between 1878 and 1880.[15] Mat was the white son of Newton and Serena Knight. Together, they built a subsistence farm on 48 acres of land that adjoined Newton’s land.[16] Fannie and Mat would go on to have nine children together: Henry Watson (1881), Martha Ann (1882), William Gailie (1884), Aleatha (1886), George M. (1889), Fred N. (1890), Claude J. (1892), Rachel Dorothy (1894), and Walter (1897).[17]

In 1881, missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints began preaching in the Jones and Jasper County areas and something about their message caught the attention of Fannie and her mother Racel.[18] Elder William Thompson Jr., a Scottish born missionary from Salt Lake City, Utah, baptized and confirmed Fannie on July 21, 1881.[19] Her mother Rachel was baptized and confirmed on the same day; her half-sister Martha Ann (daughter of Newton Knight) followed Fannie’s lead and converted the following year. Additionally, her younger half-brother, John Stuart Knight, was baptized over a decade later.[20]

Word of the Knight family’s conversions rippled through the community. In 1883, the Natchez, Mississippi Weekly Democrat reported that though the recently organized congregation was “a small one” Newt Knight, his son, and their families “are among the members.”[21] While no baptismal record has been found for Newton Knight, Mat Knight was baptized and confirmed on the same day as Fannie and Rachel.[22] Though Fannie and Mat’s marriage was not socially or legally accepted by the white community in Jones and Jasper counties, the paper’s language implies that they were at least recognized as a legitimate couple.

Despite Latter-day Saint leader Brigham Young’s strident preaching against race mixing in prior decades, there is no indication that missionaries hesitated to baptize Mat and Fannie as an interracial couple. Missionaries did however, mark Fannie’s baptismal record with the word “colored” next to her name and recorded Mat’s baptism on a separate page reserved for “white” baptisms.[23]

The conversion of Fannie, her husband, and other close family members indicates a significant relationship between some members of the Knight family and the Church. Scholars have even speculated that Fannie and Mat named their son William Gailie in honor of a missionary, Elder John William Gailey. Gailey, along with Elder William H. Crandall, had been “set on and beaten by a mob” while proselytizing in Jasper County.[24] Mat and Fannie’s oldest two children, Henry Watson and Martha Ann, were both taken before the local congregation and blessed in 1882, another sign of the strength of Fannie’s commitment to her new faith.[25] Finally the notes on her baptismal record state that she, her mother, and her sister moved to Colorado on November 13, 1884, a common place for Southern Saints to relocate in the late nineteenth century.[26] While record of their arrival in Colorado has not been found and evidence indicates that the family’s western sojourn was short-lived, these several factors taken collectively suggest the strength of Fannie’s faith.

Even still, Fannie’s religious commitment did not shield her from growing racial prejudice in the post-Reconstruction South. In 1895, Mat left Fannie to marry a white woman named Frances K. Smith.[27] Neighbor and acquaintance Martha Wheeler later recalled in an oral interview the trajectory of their marriage and the circumstances of their separation:

“They [Mat and Fannie] had seven children and he lived entirely among the negroes, attended their church and patronized their school. When the oldest children were nearly grown he quit the woman, sued for a divorce, was told he did not need one since it was illegal for whites and blacks to marry, married a white woman, a fourth cousin, and brought up a white family. He gave his 80 acres and frame house with glass windows to his negro family, but they had to lift a mortgage on it.”[28]

After Mat left her, Fannie married a man named Dock Howze, a Protestant preacher. At the same time she increasingly felt the effects of Mississippi’s racial bifurcation as Southern white politicians passed Jim Crow laws aimed at reasserting a racial hierarchy. While early census takers had recorded her race as mulatto, by 1900, Fannie was classified unambiguously as Black.[29] In a 1914 court dispute, however, she described her heritage as “Choctaw and French,” likely in an effort to distance herself from the social, economic, and political costs of being Black.[30] When further pressed by the lawyer, she insisted that “you will have to do your own judging,” relying on her physical appearance to support her claims. Some of Mat and Fannie’s children moved to Texas where, free from the Knight family’s local notoriety, they could pass as white. Eventually that line of descendants claimed that their grandmother Fannie was a “full-blooded Cherokee Indian.”[31]

Little is known about Fannie’s last years or her death. Her husband may have died in 1915, however no trace of Fannie appears in the Mississippi death certificate index and neither her or her second husband appear to be buried in the Knight family cemetery.[32]

By Keely Mruk

With research assistance from Donna Heninger

Primary Sources

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 1. CR 375 8, box 4255, folder 1, images 211 - 212. Church History Library. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2. CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, images 23 - 24, 102. Church History Library. Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Jones.” The Natchez Weekly Democrat (Natchez, Mississippi). June 8, 1881, 2.

“Meridian Mercury.” The Natchez Weekly Democrat (Natchez, Mississippi). August 1, 1883, 1.

Mississippi. State Department of Health. Statewide Index to Mississippi Death Records, 1912-1924. Dock Houze. Mississippi State Department of Health. Jackson, Mississippi.

United States. 1860 Census. Slave Schedules. Mississippi, Covington and Jones Counties. Entry for Jesse D. Knight.

United States. 1870 Census. Mississippi, Jasper County, South West Beat.

United States. 1880 Census. Mississippi, Jasper County, District Three.

United States. 1900 Census. Mississippi, Jasper County, Beat Four.

Wheeler, Martha. Interview by Addie West. Typist Vivian Andrews. Supplement Series 1, vol. 10, Mississippi Narratives, Part 5, p. 2262 – 2271. George P. Rawick, ed., The American Slave: A Composite Autobiography (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1972).

Secondary Sources

Bynum, Victoria. The Free State of Jones. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001.

Bynum, Victoria E. "‘White Negroes’ in Segregated Mississippi: Miscegenation, Racial Identity, and the Law." The Journal of Southern History 64, no. 2 (1998): 247-76. doi:10.2307/2587946.

Jenkins, Sally and John Stauffer. The State of Jones. New York: Anchor Books, 2009.

[1] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, images 23-24, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] United States, 1860 Census, Slave Schedules, Mississippi, Covington and Jones Counties, Entry for Jesse D. Knight.

[3] The Last Will and Testament of John “Jackie” Knight, excerpted in Sally Jenkins and John Stauffer, The State of Jones, (New York: Anchor Books, 2009), 70. Jackie Knight died in 1861.

[4] Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 155.

[5] Church baptismal records list her birthday as May 18th, 1864 while the 1900 Census states that her birthday is in March. United States, 1900 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County, Beat 4. See also: Victoria Bynum, The Free State of Jones, (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2001), 110, 206 – 207; Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 70.

[6] Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 62; and Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 86 – 87.

[7] The Jones County Scouts and Newton Knight’s story are covered extensively in Bynum’s The Free State of Jones and Jenkins and Stauffer’s The State of Jones. The story was also adapted for popular audiences in the 2016 film Free State of Jones, directed by Gary Ross.

[8] Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 283.

[9] Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 284.

[10] Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 259.

[11] Martha Wheeler, interview by Addie West, ed. George P. Rawick, The American Slave, Supplement Series 1, vol. 10, Mississippi Narratives, Part 5, 2269.

[12] Martha Wheeler, The American Slave, Supplement Series 1, vol. 10, Mississippi Narratives, Part 5, 2269.

[13] Victoria Bynum, "‘White Negroes’ in Segregated Mississippi: Miscegenation, Racial Identity, and the Law," The Journal of Southern History 64, no. 2 (1998): 262.

[14] Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 284.

[15] Fannie would have been around 16 and Mat around 21 at the time of their marriage. No marriage certificate has been found for them. Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 285; Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 206 – 207.

[16] Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 286.

[17] Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 206 – 207. United States, 1900 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County.

[18] The Natchez Weekly Democrat (Natchez, Mississippi) reprinted from the Ellisville Eagle (Ellisville, Mississippi), June 8, 1881, 2. Local response to the LDS Church was initially frosty, with this newspaper further reporting that it was a “shame that our people will countenance their system of foul licentiousness and abominable doctrine of polygamy, which strikes at the very foundation of our Christian civilization and sanctity of religion.”

[19] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. CR 375 8, images 23 - 24.

[20] Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, image 102.

[21] “Meridian Mercury,” The Natchez Weekly Democrat (Natchez, Mississippi) reprinted from the Meridian Mercury, (Meridian, Mississippi), August 1, 1883.

[22] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 1, CR 375 8, box 4255, folder 1, images 213 - 214, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. Despite the slight difference in naming (George Madison Knight versus George Matthew Knight) the alignment of all other biographical data suggests that this record is indeed for Fannie’s husband, Mat.

[23] For Brigham Young’s attitude toward race mixing see W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), chapters 4 and 6; for Fannie’s baptismal record see, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. CR 375 8, images 23 – 24; and for Mat’s baptismal record see Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 1, CR 375 8, box 4255, folder 1, images 213 - 214, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[24] Jenkins and Stauffer, The State of Jones, 292.

[25] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, images 211 - 212.

[26] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mississippi (State), Part 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. CR 375 8, box 4256, folder 1, images 23 - 24.

[27] United States, 1900 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County, Beat Four. Mat and Frances continued to live in Jasper County; the 1900 Census records that they had been married for 5 years (in spite of youngest son Walter being born to Mat and Fannie in 1897).

[28] Martha Wheeler, The American Slave, Supplement Series 1, vol. 10, Mississippi Narratives, Part 5, 2269.

[29] United States. 1870 Census. Mississippi, Jasper County, South West Beat; United States. 1880 Census, Mississippi, Jasper County, District Three. Both the 1870 and 1880 Census record Fannie as ‘mulatto’ while the 1900 Census records her as ‘black’.

[30] Deposition of Fannie House (Howze) in Martha Ann Musgrove et al. v. J. R. McPherson et al., Jan. 27, 1914, case no. 675, Chancery Court of Jones County, Laurel, Miss., copy in Kenneth Welch Genealogy Files. Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 167 – 171. The court case related to the estate of Mat Knight.

[31] Bynum, The Free State of Jones, 167 – 168.

[32] Mississippi, State Department of Health, Statewide Index to Mississippi Death Records, 1912-1924, Dock Houze, Mississippi State Department of Health, Jackson, Mississippi. Given the close spelling and location of death as Jones County, it seems reasonable that this record may point to Dock Howze. In a blog post hosted on Victoria Bynum’s website, family historian and Rachel Knight descendent Sondra Yvonne Bivins has stated that Fannie and Dock died under “mysterious circumstances” in 1916. However, Bivins offers no further details or evidence to this claim.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.