Litchford, Miles

Biography

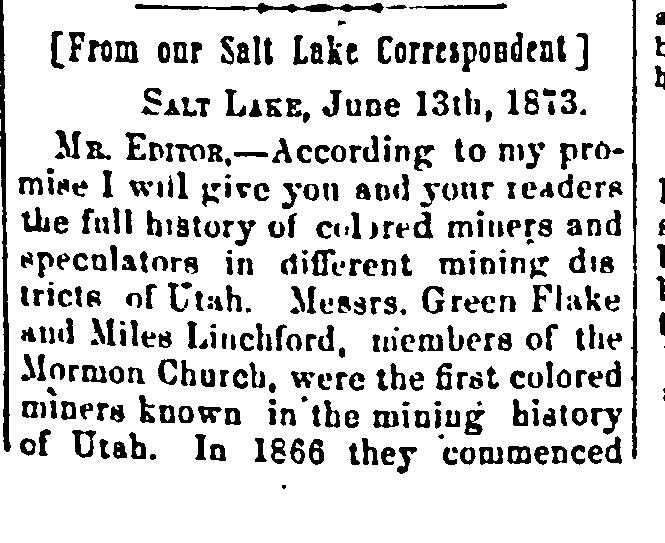

The only known evidence that Miles Litchford was baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is a passing reference in an 1873 newspaper article. Utah civil rights activist Francis H. Grice wrote to The Elevator, a historic Black newspaper in San Francisco, “Messrs. Green Flake and Miles Linchford [sic], members of the Mormon church, were the first colored miners known in the mining history of Utah.”[1] Grice knew Flake and Litchford well. The three worked jointly with each other and other Black Utahns on mining ventures in the canyons above the Salt Lake Valley.[2]

Miles Litchford was born into a well-to-do free Black family in Ohio around 1805. His father, Pleasant Litchford, had earned money to purchase his own freedom from his enslaver, who also happened to be his father (and Miles’s grandfather). As a young man, Miles left home after a disagreement with his father, suggesting they were both strong-willed. Miles headed west and lost contact with his family for many decades. His mother died in 1859 not knowing what had happened to him. Although Pleasant Litchford had no idea if Miles was alive, he wanted to provide for his long-lost son in his will. He left some valuable land to a subsequent wife in a life interest, which meant that she had the use of it during her lifetime. After she died, the land would go to Miles or to his children. If Miles died without any children, the land would go to one of Pleasant’s grandchildren.[3]

Miles next appeared on records in 1859 working as a blacksmith at Hubbard’s Ranch in Shasta County, California.[4] He then moved to Salt Lake City and worked as a blacksmith or horseshoer.[5] The 1870 census shows him living in Union Fort (South Cottonwood Ward) with a woman named Violet and her daughter Rose.[6] Violet and Rose had been taken in slavery from Mississippi to Utah in 1848. Around 1853, Brigham Young appears to have informally freed the mother and daughter through the provisions of Utah’s servitude law, An Act in Relation to Service (1852), which required people in unfree labor to assent to the use or transfer of their labor. The two women appear to have been freed along with Green and Martha Flake.[7]

Little is known about Violet and Rose. They had been enslaved in the John Crosby Jr. household in Mississippi.[8] When Crosby died, Violet and Rose became the property of William Crosby, who took them to the Salt Lake Valley. Carrie Bankhead Leggroan and Celia Bankhead Leggroan later referred to Rose as “the old lady that lived back of us” and remembered that she wasn’t married and had various partners, but then corrected their memory recalling that Rose had married a man named Jim Valentine or Banks.[9] Records are scarce, but Miles Litchford appears to have been the step-father of Daniel Freeman Bankhead (1854–), John Priestly (1858–1921), Isaac Fred Valentine or Banks (1866–1939), and Caroline Valentine Lewis (1869–1908). He was the father of Catherine Litchford Walker Patterson (1860–1917) and may also have been the father of Rose Litchford (1863–), Susannah Litchford (1867–), and Cordelia Martha Litchford (1871–1891).

Early Latter-day Saint records for Union or Union Fort are unfortunately poor to nonexistent. No members of Miles’s family are known to have left life writings, so it is not known what part religion played in the family.[10] Francis Grice’s report to the San Francisco newspaper about Miles Litchford’s religion is credible, however. Along with his restaurant in downtown Salt Lake City, Francis Grice had a farm by the Flake and Litchford families near the mouth of Big Cottonwood Canyon.[11] The three families likely interacted closely over many years. There would have been no reason for Grice to be confused about Litchford’s religion.

Miles Litchford was a large investor in the Evergreen Mine with Green Flake and Hark Wales, two Black Utah pioneers, and subsequently in the Iron Lode Mine.[12] Grice documented that Litchford and Flake were also involved in additional mines, including those named Decomposed, Abraham Lincoln, Lake Cross, Union Blue, and Rainbow.[13]

In the early 1870s, Utah leaders made a fourth bid for statehood.[14] Hundreds of residents of the territory signed the 1872 “Memorial of Citizens of Utah, Against the Admission of that Territory as a State.” The list of signers showed, “Miles Litchford, miner; Villott Lichford, farmer; Rose Catlin [Litchford], farmer; Union Fort.”[15] Many of the adult Black residents of Utah including Green and Martha Flake signed the petition. None is known to have left a record of their reasons for signing, but they were probably influenced by tensions between the church and mining interests.[16]

In the early 1890s, Miles wrote to an old friend in Ohio asking if his father was still alive. His friend wrote back with word of his father’s death and the news that Miles stood to inherit property from his father’s estate.[17] The case became a newspaper sensation. The newspapers reported that Miles’ siblings assumed the letter was fraudulent. “All doubts were dispelled last Saturday, however, when Miles appeared here and demanded his inheritance.” The newspapers reported that Miles “ran away because his father punished him, and claims to be quite wealthy—independent of what he will get from his father’s estate.”[18] Legal notices in Utah newspapers confirm his claim about his wealth. For example, in 1894 Litchford sold his interest in the Iron Lode Mine in Big Cottonwood Canyon for $7,500.[19]

While in Ohio, Miles filed for a patent on a stone saw. He designed it to be used to cut “onyx, marble, granite, and other hard stone” on both the forward and backward stroke. The United States granted him the patent.[20]

The details of his final years including his death date and death place are unknown, but he died by 1899. That year, a lawyer wrote to Salt Lake City from Columbus, Ohio, seeking Catherine Litchford Walker, the daughter of Miles Litchford. The lawyer wrote, “[Litchford] has since died and his estate is being settled and Mrs. Walker’s whereabouts is very desirous.”[21] With the help of her employer, Ella Phelps, Catherine traveled to Ohio to claim her father’s estate.[22] Catherine was Litchford’s only known living child. Although Rose has living descendants through her sons Daniel Freeman Bankhead and Isaac Fred Valentine or Banks, Miles Litchford is not known to have any living descendants or to have left a record of his life beyond what appeared in occasional legal or newspaper documents.

Although he was born in Ohio and probably died there, Miles Litchford spent considerable time in Utah Territory. While in Utah he joined the LDS Church. He formed a close acquaintance with Green Flake, a prominent Black Latter-day Saint. The two prospected together in Utah’s canyons. Both Flake and Litchford made good on their mining claims before Litchford returned to Ohio to claim an inheritance from his estranged father. From the few records that remain, Litchford’s life was marked by a sense of independence and adventure.

By Amy Tanner Thiriot

[1] “From our Salt Lake Correspondent,” Elevator (San Francisco, California), 28 June 1873. The family name was occasionally written as “Litchforth,” “Litchfield,” “Letchford,” “Leechford,” “Lichford,” or “Litzford.”

[2] Amy Tanner Thiriot, Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847–1862 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2023), 207–09, 305.

[3] Pleasant Litchford, Will, 18 March 1871, Ohio, Wills and Probate Records, 1786–1998, Ancestry.com.

[4] “Delinquent Tax List for Shasta County, California for 1859,” Shasta Courier (Shasta, California), 26 November 1859.

[5] “Will Live in Comfort on Her Own Farm,” Salt Lake Telegram (Salt Lake City, Utah), 4 March 1902.

[6] United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, South Cottonwood.

[7] Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 108–14, 151–54.

[8] Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 9, 364–65.

[9] Celia Bankhead Leggroan and Carrie Bankhead Leggroan, Interview, 3 December 1977, Helen Z. Papanikolas Papers, 1954–2001, MS 471, Marriott Library Special Collections, University of Utah, Salt Lake City; Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 207–09.

[10] In some enumeration districts in Utah Territory, the federal census taker recorded reported religion on the left side of the 1880 census pages. Unfortunately, Litchford has not yet been found in the 1880 federal census, which could have been a second confirmation of his reported religion. The 1880 census does indicate with the code “M” [Mormon] that Rose, her son Daniel, and his wife Celia were Latter-day Saint. United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Union.

[11] Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 305–06; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Little Cottonwood.

[12] “Delinquent Sale,” Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah), 9 April 1876; “Yesterday’s Real Estate Transfers,” Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah), 14 August 1894.

[13] “From our Salt Lake Correspondent,” Elevator (San Francisco, California), 28 June 1873.

[14] Maren Peterson, “Utah’s Road to Statehood: Seven Bids for Statehood,” 1 July 2021, Utah Division of Archives and Records Service.

[15] “Memorial of Citizens of Utah, Against the Admission of that Territory as a State,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), 12 June 1872.

[16] Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 144.

[17] “After Fifty-Three Years,” Marion Daily Star (Marion, Ohio), 6 June 1893.

[18] “After Fifty-Three Years,” Marion Daily Star (Marion, Ohio), 6 June 1893.

[19] “Yesterday’s Real Estate Transfers,” Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah), 14 August 1894.

[20] Miles Litchford, Patent No. 519,636, 8 May 1894, United States Patent and Trademark Office.

[21] “Lost, Strayed or Stolen,” Ogden Standard Examiner (Ogden, Utah), 7 November 1899.

[22] “Inherits an Estate,” Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah), 13 November 1899; “Negro Woman to Get Fortune,” Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah), 16 January 1902; “Will Live in Comfort on Her Own Farm,” Salt Lake Telegram (Salt Lake City, Utah), 4 March 1902; “Washerwoman Wins a Fortune,” Salt Lake Telegram (Salt Lake City, Utah), 11 April 1902.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.