Louisa

Biography

On a spring evening in 1853 a young woman named Louisa entered the waters of Spring Creek in southeastern Texas and accepted baptism into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. She was baptized alongside twenty-two others in a meeting that drew members of the young church from miles around. Preston Thomas, a Southern-born missionary, performed the ordinance, and afterwards the new members joined their fellow congregants in the home of Alexander Barron for a spirited meeting that lasted until midnight.[1]

This type of religious gathering was typical for its time. The Latter-day Saint movement was born during a period of religious fervor in the United States, and large baptismal events like this were not uncommon. However, two facts made this particular baptism truly remarkable— Louisa was a Black woman joining a predominantly white faith and at the time of her baptism Louisa was enslaved to William Cresfield Moody, who was also a recent convert to the LDS Church.

Louisa is only mentioned by name in two surviving documents—a missionary’s journal and a rebaptismal record. Through this scant information we are able to piece together a remarkable life story that took Louisa from her birthplace in Alabama as an enslaved girl to the new state of Texas and then onto Utah Territory, perhaps as a free woman. We do not have the benefit of Louisa’s perspective to tell her life story, but by carefully reading the sources of the family that enslaved her we can form a picture of Louisa’s life that tells a story of perseverance and religious devotion.

Louisa was born in Alabama in 1838.[2] Aside from this, we do not know what part of the state she was from, the names of her parents, the number of siblings she had, or how long she stayed with her natal family. We know that by the early 1850s she was living in Grimes County, Texas, and was enslaved to William C. Moody and his family. Preston Thomas’s journal described Louisa as “the calaabite [Canaanite] belonging to Brother Wm. C. Moody,” indicating her race and her status as a slave.[3] Referring to Louisa as a Canaanite is an allusion to the curse of Ham. According to the biblical story, Noah cursed Canaan to be a “servant of servants” after Ham found his father naked and drunk in his tent. The Curse of Ham was a long standing Christian justification for slavery and was championed by Joseph Smith and Brigham Young on separate occasions. Smith moved beyond that curse to advocate for government funded emancipation by the time he was killed. Young, in contrast, drew upon the curses of Cain and Ham to explain slavery, black skin, and a priesthood and temple restriction for those of Black African ancestry. His biblical justification would remain a guiding principle dictating how Black Latter-day Saints could participate in their faith from the 1850s until 1978, when the prohibition against Black men and women receiving temple ordinances and the all-male priesthood was reversed.[4]

Despite this broader racial context, Louisa and other enslaved men and women played vital, yet unsung, roles in missionary work in Grimes County. William and Harriet Moody’s home was one of the largest in their neighborhood, and Latter-day Saint missionaries often held services there while the Moody family and other Grimes residents investigated the faith.[5] Family memoirs note that hospitality was important to the Moody family and they provided dinner for guests as well as a comfortable space to discuss doctrinal issues. Harriet Moody did not accomplish this work alone but depended on the labor of the men and women she enslaved. A family memoir contains a passing mention of the scale of labor required to host missionaries, investigators, and church members, “Mrs. Moody often told how the slaves under her direction spent the entire day cooking and preparing for ‘church.’”[6] Part of the preparations included hauling, spreading, and cleaning up white sand that was used in lieu of spittoons for chewing tobacco because sand was “simpler than providing spittoons for such a large crowd.”[7] Without Louisa’s hard work the Moody family would not have been able to provide such a level of hospitality and sense of fellowship at missionary gatherings. We can imagine the complicated emotions Louisa felt as she played the dual roles of investigator and an enslaved member of the household.

During this period, Louisa decided to join the LDS Church. She was about 15 years old at the time. Her baptism was recorded in captivating detail, allowing future generations to visualize this sacred experience. Preston Thomas was serving his fourth mission, and this was the second time he had been called to Southeastern Texas.[8] He was well known among both members and non-members in Grimes County and surrounding areas. On March 30, 1853, Thomas wrote an entry describing Louisa’s baptism: “This forenoon I with Bro. Loyd[9] went out again to meet the brethren on the road and after riding some five or six miles we met Bro. Wm C. Moody in a carriage with a number of saints. I turned and went back with him to Bro. [Alexander] Barrons late in the afternoon, the families came in wagons drawn by oxen. A number of persons asking for baptism, about the time it grew dark all the saints in the neighborhood had gathered together and a great flame of fire kindled out of the pitch pine on the banks of Spring Creek.” Thomas listed the individuals he baptized. Sixteen people, including Louisa, were baptized for the first time, and seven received the ordinance for the second time.[10]

Thomas continues his description of Louisa’s baptism and the meeting that followed: “After baptizing we had a meeting at the home of Bro. Barron and I confirmed all of these persons. We had a very good meeting and many spoke by the spirit and prophesied. Bro. [John Wesley] Clark spoke in tongues and prophesied that if all those going to the Valley would be faithful not one of them should fall under the hand of the Destroyer by the way but all should live to reach the Valley. The meeting lasted until midnight when we broke up and all went home.”[11] While Thomas was a regular diarist, this baptismal event stands out in his journals for its vivid detail that continues to bring the scene to life more than 170 years later. Without this entry, the circumstances of Louisa’s life and conversion would be lost to history.

There is no record that clearly indicates when, or if, Louisa gained her freedom. A Moody family memoir, compiled in 1957, suggests that when William and Harriet Moody emigrated to Utah, they emancipated those they enslaved. This was not presented as a benevolent act, but rather as an economic choice: “Although he [William Moody] was a very wealthy man, with a large ranch or farm, much of what he knew would be lost through state laws which privileged that in order to hold the grant continued residence was necessary, he gave his slaves their freedom and left Texas for Salt Lake City, Utah March 1853.”[12] It seems plausible that William Moody emancipated those he enslaved before migrating to Utah. However, without corroborating evidence, we cannot accept this claim made many decades after the fact at face value. It is also possible that Moody sold the other men and women he claimed ownership over, and it is possible that Louisa was still enslaved when she migrated to Utah.[13]

Louisa does not appear on any pioneer company records, but it is likely she travelled with William C. Moody and his family when they departed Texas in late spring 1853. William Moody, who joined the LDS Church in 1850, began planning his family’s journey to the Salt Lake Valley in January 1853.[14] The Moodys began their westward journey by traveling from Grimes County to the Texas coast. From there, they took a steamship across the Gulf of Mexico. In 1853, Galveston was the most common point of departure in Texas, and the ship arrived in New Orleans two days later. Once in New Orleans, the family boarded a steamboat and traveled more than 800 miles up the Mississippi River before disembarking in Keokuk, Iowa.[15] They traveled overland with the Moses Daley Freight Train, departing from Council Bluffs on July 6, 1853.[16]

On September 18, after more than two months on the trail, a small group of pioneers opted to forge ahead without the main company. The company journal notes, “Brothers WC Moody & John Tippitt with their charge & families said that in consequence of their provisions being scarce & old Sister Moodys delicate health & winter near at Hand that they felt themselves Justifiable in leaving the Company in & traveling on by themselves which they did.”[17] At this point the company was just west of Fort Bridger in Wyoming, a little more than 100 miles from Salt Lake. The pioneers in the Moses Daley company arrived in the Salt Lake Valley on September 29, and presumably the Moody and Tippitt splinter group arrived several days earlier.[18] Fulfilling the prophesy issued at Louisa’s baptism five months earlier, no members of their pioneer company died enroute to Utah. In the Moses Daley company journal, John Alexander Ray wrote, “[we] have been so blest of the Lord that not one of us have Died by the way.”[19]

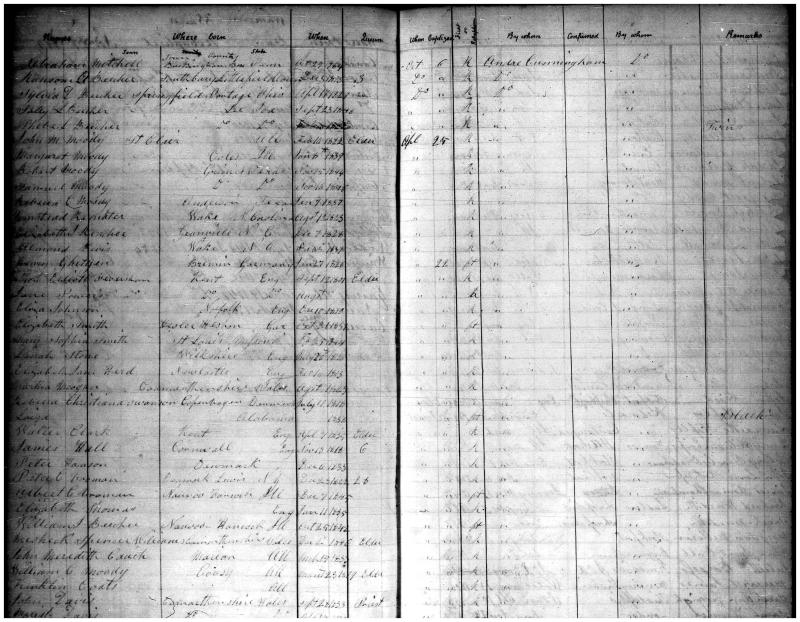

Once in Utah, the only document to indicate Louisa’s presence is a record of her rebaptism in 1856 or 1857, when Louisa was 18 or 19 years old. Her rebaptism was an act of religious devotion during a period known as the Mormon Reformation. Brigham Young admonished Latter-day Saints to recommit themselves to building the kingdom of God, and rebaptism represented a remission of sins and a renewal of covenants.[20] Louisa was rebaptized by an elder living in her ward, Andrew Cunningham, again in a mass baptismal event alongside dozens of her fellow congregants. At this time, she was living in the 15th ward, in what is now the Poplar Grove neighborhood of Salt Lake City. The Moody family also lived in this ward, but without census data, it is impossible to know if Louisa continued to live with the Moody family and in what capacity. Was she free or enslaved? If free, how did she sustain herself? If enslaved, what did her work and religious life look like in the decade leading up to the Civil War?

After her rebaptism, Louisa disappears from the historical record altogether. Unless additional sources come to light, it is impossible to know if she married, had children, what she did for work, or when and where she died. The Moody family moved out of Salt Lake County by 1860, and Louisa is not included in their households at that time or thereafter.

Without a detailed journal entry documenting Louisa’s baptism in Texas and a single entry in Latter-day Saint records in Utah, Louisa may have been lost to history. Those two sources, nonetheless, offer an intriguing glimpse into her life and her epic westward journey. More poignantly, those sources suggest a religious commitment to her faith community and a desire to fulfill the covenants she made on that spring evening in Texas, in 1853, in which “many spoke by the spirit and prophesied” and the fervor of the event captivated the new converts until midnight.[21]

By Julia Huddleston

[1] Daniel Hadlond Thomas, Preston Thomas: His Life and Travels (journal transcription, 1942) MS 1928, page 154, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Fifteenth Ward, CR 375 8, box 2145, image 33, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] Thomas, Preston Thomas, 154. This misspelling “calaabite” seems like a typist error in Preston Thomas’s journal typescript from the 1940s. The “L” and the “b” were typed over with “n”s in the typescript.

[4] W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), chapters 4-7.

[5] Thomas, Preston Thomas, 24.

[6] E. Grant Moody, Moody Family Record (Dr. Thomas Moody Family Organization: Tempe Arizona), 126.

[7] Moody, Moody Family Record, 126.

[8] Thomas, Preston Thomas, 24.

[9] An otherwise unidentified member of the Church in the area.

[10] Thomas, Preston Thomas, 154.

[11] Thomas, Preston Thomas, 154.

[12] Moody, Moody Family Record, 124.

[13] Amy Tanner Thiriot, Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847-1862 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2023), 31-32.

[14] Thomas, Preston Thomas, 139.

[15] Peter Stubbs autobiography, 1903, MS 33950, 38-39, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. Stubbs was in the Moses Daley company, which took the same route up the Mississippi River that the Moody family took.

[16] Moses Daley Freight Train, 1853, Church History Biographical Database, Accessed June 2025.

[17]John A. Ray, Moses Daley Freight Company Report, 1853, MS 328, 4, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[18] Moody, Moody Family Record, 126.

[19] Ray, Moses Daley Freight Company Report, 8.

[20]Paul H. Peterson, “The Mormon Reformation of 1856-1857: The Rhetoric and the Reality,” Journal of Mormon History 15 (1989): 59-87.

[21] Thomas, Preston Thomas, 154.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.