Meads, Rebecca Henrietta Foscue Bentley

Biography

In the county of Claiborne, Mississippi, early in 1836, Lewis Foscue, planter and slaveholder, wrote his last will and testament. In it, he disposed of his property, both real and human and in doing so made special provisions for one of his enslaved girls, a person he identified in his will as “Rebecca Henrietta.” Between her inclusion in Foscue’s will as a young girl and her later conversion to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as an adult and subsequent move to Utah, Rebecca’s life took several unexpected turns. Most noteworthy, she became one of only two known formerly enslaved people to be sealed to her spouse and receive full temple rituals in the LDS faith. Her life thus represents a remarkable journey, from enslavement in Mississippi to freedom and fealty in Utah, an unusual racial and religious story in nineteenth century America.

When Lewis Foscue wrote his will in 1836, he had never married, so most of his bequests were to friends and to his sister, Sarah Ann Foscue Foy. However, he made special provisions for one young enslaved girl, Rebecca Henrietta. He described her as the daughter of an enslaved woman named Easter and ordered that after his death three other of his enslaved “girls” be sold to finance Rebecca’s emancipation. He granted his sister Sarah ownership of his “negro woman Princess aged about thirty years and her three children” but stipulated that after Sarah died, ownership of Princess and her children would pass to Rebecca.[1] Lewis’s unusual specifications regarding Rebecca indicate her unique position among the people Lewis enslaved. The favor he showed Rebecca was no doubt influenced by the fact that Lewis was Rebecca’s biological father, or at least Rebecca claimed him to be her father on LDS Church membership records later in life.[2]

Lewis Foscue died within three months of writing his will and despite his best intentions for Rebecca, his wishes went unfulfilled. Foscue’s heirs may have taken issue with his magnanimous plans for his biracial daughter or the laws of the state of Mississippi may have prevented their fulfillment. Rebecca was likely only three or four years old when Foscue died but he did not name a guardian for her in his will. He may have hoped that his sister Sarah would bring Rebecca into her household and follow his wishes for her eventual emancipation but Sarah did not do so.

The laws of Mississippi likely further complicated matters. Lewis Foscue had lived most of his life in North Carolina before moving to Mississippi and may not have been aware of the difficulties surrounding slave manumissions in his new state. From 1805 until 1865, a special act of the state legislature was necessary to legally emancipate an enslaved person.[3] An order set forth in a will was not deemed a legal manumission. Mississippi legislators desired to limit the number of free black people within state boundaries, consequently they enacted laws which mandated that enslavers post bonds to ensure their former slaves never became wards of the state. They also required emancipated slaves pay fees to annually renew free papers.[4] Foscue’s will, in summary, could not override the laws of the state of Mississippi.

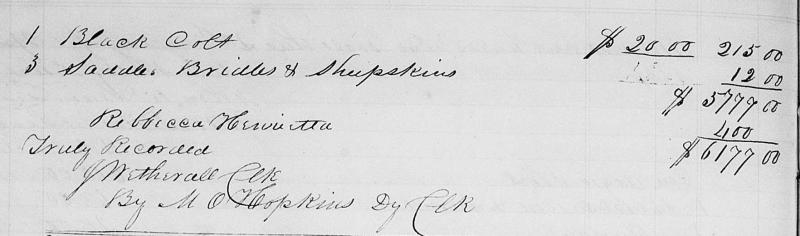

As part of the probate of Foscue’s will, a committee made an inventory of his property before settlement. The inventory listed Rebecca Henrietta as part of the estate and valued her at $400.00.[5] After his heirs received their bequests, the court ordered the executors of Foscue’s estate to hold a sale to dispose of the remainder of his property. At this sale on May 28, 1836, neighboring planters purchased the three enslaved “girls” Foscue ordered sold to finance Rebecca’s freedom and together they fetched a collective price of $1490.00. However, instead of manumitting Rebecca with these proceeds, it appears she was sold along with her mother Easter and her mother’s young son, Darby, to a planter named James Watson. The court record documents the sale of an enslaved girl named “Becky” and lists an unusually low price of twenty dollars paid for her purchase.[6] There was no “Becky” enumerated in the earlier inventory, making Rebecca the only logical person to whom “Becky” could have referred. Evidently, instead of receiving her freedom, Rebecca spent an unknown length of time enslaved on Watson’s large Mississippi plantation where he held over ninety slaves in 1840.[7]

Foscue’s sister Sarah Foy died in 1852, and in her will she again failed to meet her brother’s expectations. Instead of granting Rebecca ownership of Princess and her three children as specified in her brother’s will, Foy instead divided the four enslaved people between two different heirs.[8] All of Foscue’s wishes for his young daughter thus went unfulfilled.

For twenty years after her sale to James Watson, Rebecca’s life circumstances are not known. A search of the petitions for special acts of the Mississippi Legislature has not yielded any record of Rebecca’s emancipation.[9] It is not until 1860 that her name appears again in the historical record. At that point, she was a free woman living in Cincinnati, Ohio. It is possible that she left Mississippi when she was finally manumitted and traveled north to escape the possibility of being re-enslaved. It is also possible that she escaped from slavery and made her way to Cincinnati, a prominent hub on the Underground Railroad.

The 1860 U.S. Census lists a seamstress, Rebecca Bentley living with a “mulatto” couple and their daughter in Cincinnati.[10] Twenty-seven-year-old Rebecca’s race was also designated as “mulatto.” Her surname, Bentley, could indicate she had married. Alternately, she may have taken the family name of a subsequent enslaver or employer who she may have lived with prior to 1860, or Bentley could have been the name she chose for herself after her emancipation. Later church membership records list both Foscue and Bentley as her surnames.[11]

Between the summer of 1860 when she appeared on the federal census and January 1862, Rebecca’s life changed dramatically. It appears she met and married Nathan Meads sometime in 1860 or 1861. Meads converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1849 in his native Britain, came to American in 1860, and after stopping over in Ohio, used a Perpetual Emigration Fund loan to make his way to Utah Territory with Rebecca by 1861.[12]

Rebecca joined the church in Ohio perhaps after meeting Nathan Meads and learning of the LDS faith from him. The Cincinnati Ward Record of Members documents her baptism on April 1, 1861. Nathan, the man who became her husband, performed the confirmation the same day.[13] Rebecca had two cousins, Eliza Ann Foscue Lee Wells and Mariah Amanda Foscue Smith Thomas who joined the church in Texas around 1849 and migrated to Utah, so she may have learned of Mormonism from their conversions, but there is no evidence that they communicated directly. It is more likely that Nathan Meads introduced her to the church.

Upon their arrival in Utah Territory, probably in the summer or autumn of 1861, Rebecca and Nathan settled in the Salt Lake Eleventh Ward where they would live for the rest of their lives. Rebecca gave birth to their first child, a daughter, Margarett Henrietta Meads, on January 23, 1862.[14]

It was customary, at that time, for church members to undergo a second baptism and confirmation upon arriving in “Zion” as a recommitment to the faith. Rebecca and Nathan Meads accepted rebaptisms and confirmations on May 1, 1862 as devoted Latter-day Saints.[15]

Rebecca listed her father as Lewis Foscue in the ward membership record. She also specified Louisiana as her birthplace on church and government records while her children reported that Ohio was the state of her birth. Lewis Foscue’s will was registered in Claiborne County, Mississippi, but that county sits directly across the Mississippi River from Louisiana, so her claim is not impossible. After arriving in Utah, Rebecca’s race was consistently listed as “white” in all government sources and her church records carry no racial notations typical of many early members of African descent. By the time she arrived in Utah, it seems that she passed as white. Rebecca and Nathan received LDS temple rituals known as endowments and were sealed (an LDS marriage ritual believed to extend the marriage bond into the eternities) in the Endowment House on June 13, 1863, giving further evidence that church leaders were either ignorant of Rebecca’s racial heritage or made an exception to the church’s racial priesthood and temple bans.[16]

The Meads were parents to five children born in the 1860s and 1870s, but sadly, all but their eldest daughter, Margarett Henrietta, succumbed to childhood illnesses and common diseases. Their youngest son, Matthew Henry, contracted diphtheria and died as a two-year-old.[17] Two of their daughters, Sarah Rebecca and Florence Ellen died in 1870 and 1873, respectively, both at the age of five years.[18] Nathan Foscue lived long enough to be baptized, but in 1882, typhoid fever claimed the eleven-year-old’s life.[19]

Nathan and Rebecca were contributing members of their local congregation. The birth and death dates of each of their children are listed in the Eleventh Ward membership records, but no baptismal dates, if they once existed, have survived in the ward records for any Meads children except Nathan Foscue Meads.[20] Their surviving daughter, Margarett, appears in church records her entire life and she had all her children baptized, so despite the lack of written confirmation, it seems the Meads reared their children in the church.

The faithfulness of the Meads is shown in other ways, as well. Nathan and Rebecca accepted third baptisms and confirmations on February 3, 1876.[21] They donated money for the construction of the Salt Lake Temple and Nathan was ordained to the office of High Priest in the church’s lay priesthood.[22] This is a good indication that he was a practicing member of the church and Rebecca’s race was not seen as an impediment to his priesthood status.

Rebecca died on August 4, 1881 and was buried in the Salt Lake City Cemetery.[23] It is uncertain how old she was at her death. The death register listed her birth year as 1837, which is certainly incorrect given that Lewis Foscue described her as an enslaved girl in his 1836 will. It is more likely she was born in 1833 and was about forty-eight years old when cancer took her life.[24] She remained a faithful member of the LDS church all her life and her funeral took place in the Eleventh Ward schoolhouse.[25]

After her premature death, Nathan remarried twice. When he died, Nathan and Rebecca’s surviving daughter, Margarett, petitioned the court to name an impartial person as administrator of his estate. She argued that Nathan’s third wife should not be awarded his “homestead” because it had been “acquired” by Nathan’s first wife, Rebecca Meads. Margarett’s argument implies that Rebecca may have received at least a portion of her rightful inheritance from her father.[26]

It is unclear whether Rebecca’s mixed racial heritage was always known or was later discovered when her children and grandchildren were born. Her access to higher temple ordinances was used as an example of an exception made to the church’s racial priesthood and temple bans. In 1885, Lorah Berry, a Mormon whose father was biracial, petitioned her stake leader, Joseph E. Taylor, to allow her to be endowed and obtain a polygamous sealing. Lorah based her claim on a precedent she was aware of in the Salt Lake Stake. She argued that "Brother Meads" of the Eleventh Ward had married a “quadroon” who had received her endowment and an eternal sealing. Lorah said that the Meads children were “very dark.” Her plea was apparently denied by LDS church president John Taylor despite her stake leader verifying the truth of her claim.[27]

To date, only two formerly enslaved black women are known to have received a temple endowment and sealing during their lifetimes and Rebecca Henrietta Foscue Bentley Meads is one of them.[28]

by Tonya S. Reiter

Primary Sources

“Advertised Letters.” Cincinnati Daily Press, (Cincinnati, Ohio), 29 April 1860, 1.

Bureau of Vital Statistics. Utah Death Index, 1847-1966. Utah State Archives and Records Service. Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Card.” Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City, Utah). 8 August 1881, 3.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Eleventh Ward, Part 1. CR 375 8, book 1894, folder 1, images 56, 68, 479-480. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Ohio (State), Part 1. CR 375 8, box 5007, folder 1, image 199. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Foscue, Lewis. Last Will and Testament. 5 Jan 1836. Claiborne County, Mississippi, Chancery Clerk. Transcript. Mississippi, U. S., Wills and Probate Records, 1780-1982.

Foy, Sarah A. Foy. Last Will and Testament. 4 Feb 1852. Macon County, Alabama, District and Probate Courts, Estate Papers, 1832-1940. Alabama, U. S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999.

“In the 11th Ward.” Deseret Evening News (Salt Lake City, Utah). 5 August 1881, 2.

“In the 11th Ward.” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah). 10 August 1881, 16.

Mississippi Probate Records, 1781-1930. Claiborne County Probate Records 1834-1836, vol. G. Microfilm 005842424. Family History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

United States. 1840 Census. Mississippi, Claiborne County.

United States. 1860 Census. Ohio, Hamilton County, Cincinnati Ward 6.

United States. 1880 Census. Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City.

Utah. County. District and Probate Courts. Probates. Series 1621, Box 73, Folder 27. Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Secondary Sources

Davis, Denoral. “A Contested Presence: Free Blacks in Antebellum Mississippi, 1820-1860.” Mississippi History Now.

High Priest Genealogies. Salt Lake Stake of Zion. Microfilm 924617, item 4. Family History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Klebaner, Benjamin Joseph. “American Manumission Laws and the Responsibility for Supporting Slaves.” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 63, no. 4 (October 1955): 443-453.

Meads, Rebecca Henrietta Foscue. FindAGrave.com.

[1] Last Will and Testament of Lewis Foscue, 5 Jan 1836, Claiborne County, Mississippi, Chancery Clerk, transcript p. 138-139, accessed at ancestry.com, Mississippi, U. S., Wills and Probate Records, 1780-1982.

[2] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eleventh Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, box 1894, folder 1, image 479, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] Benjamin Joseph Klebaner, “American Manumission Laws and the Responsibility for Supporting Slaves,” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 63, no. 4 (October 1955): 443.

[4] Denoral Davis, “A Contested Presence: Free Blacks in Antebellum Mississippi, 1820-1860,” Mississippi HistoryNow, (accessed 22 Nov 2020).

[5] Mississippi Probate Records, 1781-1930, Claiborne County Probate Records 1834-1836, vol. G, pgs. 461-463, microfilm 005842424, image 254, Family History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[6] Mississippi Probate Records, 1781-1930, Claiborne County Probate Records 1834-1836, vol. G, p. 497-498, microfilm 005842424, image 272, Family History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[7] United States, 1840 Census, Mississippi, Claiborne County.

[8] Last Will and Testament of Sarah Ann Foscue Foy, 4 Feb 1852, Macon County, Alabama, District and Probate Courts, Estate Papers, 1832-1940, accessed at ancestry.com, Alabama, U. S., Wills and Probate Records, 1753-1999.

[9] Digital Library on American Slavery, Race and Slavery Petitions Project, University of North Carolina Greensboro, (accessed 11 Nov 2020).

[10] United States, 1860 Census, Ohio, Hamilton, Cincinnati, Ward 6.

[11] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eleventh Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, book 1894, folder 1, image 479, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[12] See: Nathan Meads in Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Pioneer Database, 1847-1868, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah, (accessed 22 Nov 2020).

[13] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Ohio (State), Part 1, CR 375 8, box 5007, folder 1, image 199, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[14] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eleventh Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, book 1894, folder 1, image 68, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[15] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eleventh Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, book 1894, folder 1, image 56, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[16] Rebecca Henrietta Foscue Bentley (KWJ6-69R), ordinance records on FamilySearch.org, (accessed 22 Nov 2020).

[17] Bureau of Vital Statistics, Utah Death Index, 1847-1966, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[18]Bureau of Vital Statistics, Utah Death Index, 1847-1966, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah. And Bureau of Vital Statistics, Utah Death Index, 1847-1966, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[19] Bureau of Vital Statistics, Utah Death Index, 1847-1966, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[20] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eleventh Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, book 1894, folder 1, image 64, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[21] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eleventh Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, book 1894, folder 1, image 479-480, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[22] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Eleventh Ward, Part 1, CR 375 8, book 1894, folder 1, image 98, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah and High Priest Genealogies, Salt Lake Stake of Zion, microfilm number 924617, item 4, Family History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[23] Rebecca Henrietta Foscue Meads, FindAGrave.com.

[24] Bureau of Vital Statistics, Utah Death Index, 1847-1966, Rebecca Meads, 1881, Utah State Archives and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[25] “In the 11th Ward,” Deseret Evening News, (Salt Lake City, Utah), 5 August 1881, 2; “Card,” Deseret Evening News, 8 August 1881, 3; “In the 11th Ward,” Deseret News, 10 August 1881, 16.

[26] Utah, County, District and Probate Courts, Probates, Series 1621, Box 73, Folder 27, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[27]Joseph E. Taylor to John Taylor, September 5, 1885, John Taylor papers, CHL, CR 1 180, Box 20, File 3, typed transcript held by Connell O’Donovan and quoted in Connell O’Donovan, “Tainted Blood-The Curious Cases of Mary J. Bowdidge and Her Daughter Lorah Jane Bowdidge Berry,” posted 13 February 2013 on The Juvenile Instructor blog, (accessed 22 Nov 2020.

[28] The other is Harriet Church, formerly enslaved and later married to Thomas Church. See: Harriet Elnora Burchard (KWJ6-Z9G), ordinance records on FamilySearch.org, (accessed 22 Nov 2020).

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.