Perkins, Sylvester

Biography

Sylvester Perkins was born in Utah Territory as one of the youngest children of Frank and Esther Perkins.[1] Sylvester’s long life began near the end of legalized slavery in the territory. After Congress outlawed slavery in all US territories in 1862, Sylvester experienced the vicissitudes inherent in being a member of a large newly freed family whose members struggled to find viable livelihoods and survive in the early days of their emancipation. In addition, many members of his immediate family died prematurely and in poverty. Sylvester overcame the obstacles of his early life, becoming a successful rancher, farmer, husband, and father. He bought farmland in Mill Creek, Salt Lake County, Utah. There he, his wife, and their children worked hard to sustain themselves with their own produce and livestock.

When the enslaved family of Frank and Esther Perkins arrived in the Great Basin in the fall of 1849, they had traveled from Missouri with Reuben and Elizabeth Perkins who had converted to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in 1848 and 1849 respectively. While the date of his conversion is unknown, Sylvester’s father, Frank, was a baptized member of the LDS church.[2] His wife, Esther, had also likely accepted baptism.[3]

Both the White and Black Perkins families originally lived in the Salt Lake Seventh Ward, but by October 1850, Reuben and Elizabeth Perkins and their son Jesse’s family began farming north of Salt Lake City in the Sessions Settlement, later called Bountiful.[4] The Perkins families, like many other slaveholding Mormon converts, relied heavily on the labor of the people they enslaved to establish their new homes on the western frontier.

Frank and Esther brought five or six children with them across the plains and Esther gave birth to another five or six after settling along the Wasatch Front. Although the total number of their children is unknown, all were probably born into slavery. Sylvester was likely born around 1855 although no definitive birthdate is known.[5] Sylvester is listed in the 1856 Utah Territorial Census, so he was born by the time it was taken in about February of that year.[6] He was given a name and a priesthood blessing by William Atkinson in the North Mill Creek Kanyon Ward on November 18, 1861. His birthdate in that record is listed as December 23, 185_. The clerk noted that Sylvester was “a colored boy,” but described his parents as “slaves” and went on to write, “Parents belonging to R. Perkins.”[7]

The designation of Sylvester as “a colored boy,” not “a slave,” coincides with a new interpretation of “An Act in Relation to Service,” the law that the Utah legislature passed in 1852 to govern “servitude” in the territory. Frank and Esther came into the territory enslaved, but Sylvester was born in Utah Territory after the act passed and therefore may have been considered free according to the terms of the 1852 law. A close reading of the law and the debates surrounding it suggest that lawmakers did not intend for a parent’s condition of servitude to pass to children born in the territory. Those who came to the territory enslaved would die enslaved but children born to enslaved parents in Utah may have been considered free.[8] It is not clear if enslavers or their enslaved were aware of the law or followed it provisions. Regardless of the intent of the Act, Frank and Esther and their children appeared on the 1860 US Census Slave Schedule for Davis County.[9]

After Frank, Esther, and their children’s emancipation, they moved back to Salt Lake City.[10] Unfortunately, Sylvester’s mother, Esther, died on December 20, 1865 when he was still a young boy.[11] By 1869, most of Frank and Esther’s children had also died leaving Frank to care for his two youngest children, Sylvester and Charlotte. Frank’s eldest surviving daughter, Mary, brought Charlotte into her home as a foster daughter.[12] Evidence from surviving family histories suggests that British LDS converts Richard George Jones and his plural wife Elizabeth Baker Jones unofficially adopted Sylvester. One such history stipulates that “[Sylvester] was about 11 or 12 years old” when “Richard Jones took him in and he lived with the Joneses until he was about 21 years old.”[13]

After Richard and Elizabeth Jones married in 1864, they rented William Muir’s farm in the Sessions Settlement.[14] The Latter-day Saint North Kanyon Ward encompassed this community. Reuben and Elizabeth Perkins lived and farmed in the same ward.[15] Richard and Elizabeth Jones and the Perkins family would have known each other through church association. In addition to this connection, two of Reuben and Elizabeth Perkins’ sons lived in the Salt Lake Nineteenth Ward with Richard Jones’s first wife Sarah making it even more likely the two Jones families and the extended Perkins families were acquainted.[16]

It must have been soon after Esther Perkins died, around 1865, when Sylvester began to live with Richard and Elizabeth Jones. Both Jones and Perkins family reminiscences mention this turn of events.[17] More than one hundred years after the Joneses took Sylvester in, two of Richard and Elizabeth’s granddaughters wrote that “When Abraham Lincoln freed the slaves, a Mr. Perkins, who owned a family of slaves, gave them their freedom. However, they did not want to leave Utah nor did they want their freedom. Mr. Perkins asked Richard Jones if he would take the eleven-year-old boy, Sylvester. Richard took him into the family and he was accepted and treated as one of them. The boy was cheerful, well adjusted, and happy. He lived with them for fifteen years.”[18]

The Jones descendants’ view of how the newly emancipated Perkins family members viewed their situation is typical of the approach many Latter-day Saint slaveholding families took in framing their histories. They sentimentalized the relationship between their forebears and their enslaved and often maintained the fiction that the enslaved really did not want to be free.

Another remembrance suggests that members of Frank Perkin’s family did not have an easy time immediately after gaining their freedom. This source claimed that “when slavery was abolished, he [Reuben Perkins] just released his slaves and let them survive as best they could.”[19] This scenario best matches surviving evidence. Although Sylvester did not document his life story, his daughter, Mary Lucile Perkins Bankhead told an interviewer what she knew about her father’s early life. She believed it was Sylvester’s father, not Reuben Perkins, who asked the Jones couple to take Sylvester into their household. Lucile told what she understood the circumstances to have been: “His folks gave him to Mrs. Jones . . . They say that grandpa Perkins . . . did not provide for his family at all. So they gave Dad to Mrs. Jones. He worked for her.”[20] It is not hard to imagine that widowed Frank Perkins struggled to care for and support his young children and became willing to put them in the custody of friends or relatives.

Sylvester would have been free when he began living with the Jones family, but Lucile mentions her dad worked for Elizabeth Jones. Sylvester would have been old enough to contribute valuable help on the farm and it is likely the Joneses expected him to pitch in. Richard Jones and his first wife, Sarah Jeffcott Jones owned and operated a bathhouse at a natural hot spring located just south of the Davis County line in Salt Lake City. Richard Jones divided his time between the farm where Elizabeth lived and the bathhouse where Sarah offered mineral baths and lunch to visitors. When Richard and Elizabeth’s children were old enough, Richard often took them to lend a hand and do chores for Sarah at the bathhouse.[21] Sylvester may have joined them and worked there, as well as on the farm. About two miles south of the hot springs, Salt Lake City owned the Warm Springs Bath House. Both bathhouses sat within the boundaries of the Salt Lake Nineteenth Ward. It is possible that Sylvester Perkins also worked at the Warm Springs Bath House on occasion and was photographed there.[22]

Without a firsthand account, it is impossible to know exactly what position Sylvester occupied in the Jones family and how he viewed those years. His daughter had nothing negative to say about his experience with the Joneses and from the Jones descendants’ later point of view, Sylvester was an integrated member of the household. Richard and Elizabeth Jones’s eldest daughter, Margaret, told her daughter about growing up with Sylvester: “Sylvester melted into the Jones family as if her [sic] were born there . . . [Margaret and Sylvester] played and worked and grew up together. One day Sylvester cut his finger, and Margaret was concerned, but Sylvester simply said he had been angry over something, and he was just letting some of his mad run out.”[23] Another Jones granddaughter wrote of Sylvester’s connection to Richard and Elizabeth’s eldest son, David, “Sylvester liked Richard and Elizabeth’s son David very much . . . Sylvester gave David a pocket knife, which he prized very highly.”[24]

Late in the 1870s, Richard and Elizabeth Jones moved their family to Hooper, Utah in Weber County. By 1882, they had followed Elizabeth’s family farther east to homestead in the newly developing community of Sandridge, later renamed Roy, Utah.[25] Sylvester went north with them, being remembered as “the first black” person who came to Roy.[26] The Jones family was a devout Latter-day Saint family. It is possible that while living with them Sylvester was baptized but so far no record has been found to verify that he was a member of the Church. Because he received a priesthood baby blessing, it is possible his parents arranged for his baptism before he left their home and the record of that ordinance has been lost.[27]

Sources conflict as to exactly how long Sylvester lived with the Jones family but it likely was at least ten years. He was in his early twenties when he left Roy to work as a ranch hand in Promontory, Box Elder County, Utah. Evidently, Sylvester acquired his job as a cowboy thanks to Elizabeth Jones. It seems he learned to handle horses while working on the Jones farm.[28] Elizabeth Jones may have known ranchers in Promontory who were looking for help. It is possible she wanted to offer Sylvester better opportunities than were available for him in the small town of Roy. In any case, Sylvester’s daughter Lucile recounted, “Dad . . . was a cowboy out on the Promontory . . . He ran horses for a Mrs. Jones.”[29] Lucile elaborated on this when she wrote about her family for the Daughters of Utah Pioneers publication, The Story of the Negro Pioneer. “Mrs. Jones had him go to Promontory to take care of horses for a Mr. Lee and William Bosley. They also had cattle, and Father learned to be a good cowboy. He worked for a share in the ranch, which he did not receive. He had a brand registered SJB for horses and cattle he owned.”[30] Sylvester did, in fact, register a brand on September 15, 1890. It was to be placed on the left hip or thigh of the animal. It was an upside down capital “SJ,” both with seraphs.[31] It is very likely that Sylvester worked at the Hillside Ranch at Blue Creek breaking and training horses. However, Lucile’s memory proved correct in respect to the men her father worked with. L. C. Lee was the on-site ranch manager and William Bosley was an employee.[32]

In 1893, Sylvester bought land in Mill Creek, about nine miles southeast of downtown Salt Lake City. His sister and her husband Mary Ann Perkins and Sylvester James had moved to Mill Creek from the city center and were farming there. The Jameses had sold some property to their son William who sold four acres to his uncle, Sylvester Perkins.[33] Mill Creek was home to several Black farming families, most of them connected through familial or marriage relationships.[34] Perhaps after Sylvester was disappointed in his expectation to receive a share in the Promontory ranch, he decided to work for himself, farming on land he owned close to other family members. Sylvester, who had been born to enslaved parents, now, through his own efforts, became a landowner and began creating a legacy for his descendants.

On October 11, 1899, Sylvester married Martha Ann Stevens, the granddaughter of pioneer Green Flake. They were married in Mill Creek by Justice of the Peace Alva Keller in a double ring ceremony. The other couple married that day was Sylvester’s niece Nettie James who married Louis Leggroan. Sylvester’s daughter Lucile thought her father and mother had met in Mill Creek when Martha and her sister came from Idaho for a visit.[35] Martha’s family had been living near Corinne for several years while Sylvester was ranching close by, so it is possible that they met at that time in Box Elder County, especially given the fact that when Sylvester applied for his marriage license he said he resided in Box Elder County.[36]

The 1900 census shows Sylvester and Martha farming in Mill Creek. It also shows that within the first year of their marriage, Sylvester’s eldest brother Ben moved in with the newlyweds.[37] He stayed with them until his death nine years later. While ranching Ben was snow blinded and must have required considerable help from the couple.[38]

In addition to subsistence farming, Sylvester and Martha worked at other jobs to supplement their income. Sylvester drove horses for Bagley’s, a company that cleared and maintained local roads. In the summer, he worked for wages on a neighbor’s hay farm. Martha cleaned houses. In retrospect, their daughter Lucile realized they were poor but more importantly remembered that growing up on the farm, “We seemed to have everything that we wanted, everything that we needed.”[39] They lived on the farm continuously for over three decades, but traveled briefly to Idaho Falls to work on one of the Snake River dams along with Martha’s father and family. The Perkinses traveled by covered wagon for seven days to reach the construction site. In addition to the team pulling the wagon, Sylvester brought an extra horse so that he could rotate the team and rest one horse while the others pulled.[40]

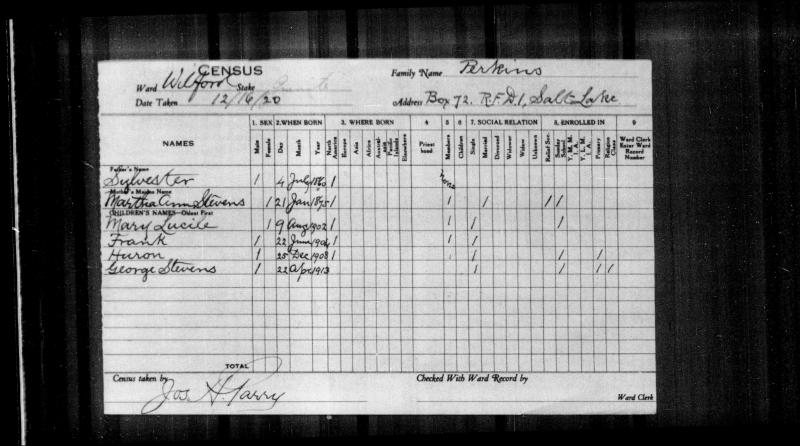

Sylvester and Martha had four children who were born and raised in Mill Creek. Mary Lucile was born August 9, 1902; Frank joined the family two years later and was followed by Huron who was born on Christmas day 1909; four years later George Stevens was the last to arrive. The Perkins family enjoyed their life together, at least according to Lucile’s memory of that time: “Mother and Father got along fine. I do not believe I ever heard my mother and father quarrel. I can remember Mother getting upset sometimes. Dad would go outside. Then he would come back, and he would say, ‘Little Mama, do you feel better now?’”[41] She described Sylvester as, “one of these kind who never said very much. He was a very placid man.”[42] “Dad was an awful quiet man. He did not make too much to-do about anything. He liked his horses. He had plenty of horses.”[43]

Sylvester occasionally treated his children to tales of his days as a cowboy. He told them stories about the horses he had trained and broken. He kept good horses on the farm and knew how to breed them successfully. Sylvester kept a stallion to provide stud services to other ranchers and farmers in the Salt Lake Valley.[44]

In addition to horses, Sylvester and his family kept a cow, pigs, chickens, and grew vegetables for their own table. They had a peach orchard and cultivated black currants and strawberries for sale. The currants were so popular at the time that they shipped cases of them to Wyoming. Wheat was another important crop on the Perkins farm. When threshing time came, Sylvester and his neighbors took turns helping each other thresh the grain. Like the other farmers in Mill Creek, Sylvester took a team of horses and a wagon to the canyons east of their home to gather logs for winter firewood.[45]

Living and farming near relatives in Mill Creek provided the Perkins family opportunities to socialize. They went on outings and had potluck dinners and picnics with the Leggroan family. Home dance parties provided entertainment for the adults who danced and for their children who, instead of sleeping, cracked the door to watch the “old people” enjoying themselves and laugh at the way they danced.”[46]

In 1915, the Black Mill Creek farmers received an honor from the National Negro Farmers and the Rural Teachers’ Association. The association planned to hold a convention in San Francisco, California and its president asked Utah’s Third District Court Judge, Frederick C. Loofbourow, to appoint thirteen Black farming delegates from Utah. He chose seven from Mill Creek. It seems Sylvester Perkins was one of those he named. In the process of reporting his choice, Judge Loofbourow commented on discovering how many Black residents had taken up homesteads in Utah. He also reported that even though the overall number of Black Utahns was low, more than twenty percent of Black Salt Lake residents were homeowners.[47]

In December 1905 Sylvester had also come to the attention of the Third District Court when he was elected, along with twelve other men, to act as a juror for District No. 56 in 1906. His name appeared in the list published in the Salt Lake Tribune in the company of some of Mill Creek’s prominent citizens including James D. Cummings who served as an early bishop in the Wilford Ward. A total of 340 voters weighed in on his selection to the jury pool.[48]

One of the indications that Sylvester might not have had the opportunity to attend school as a child is his illiteracy as an adult. He signed his marriage certificate with a mark, not a full signature. In 1965, when asked to give a history of her father, his oldest daughter Lucile wrote, “These Negro children were not always treated so well and their education was sparse. My father could not read or write until I started to school. I would bring my lesson books home and he would recite them with me, and in this way he got some education and learned to write.”[49]

Not only did Lucile tutor her father, she also had the responsibility to cook and clean for him and her brothers when Martha worked out of the home. Lucile learned to cook as a young girl around the age of twelve. On one occasion, when her mother traveled to California with a family she worked for, Lucile had to prepare all the meals for an extended period. Fortunately, she liked cooking so when Sylvester came home for “dinner” in the middle of the day, “there was meat on that plate and usually hot bread. . . There was plenty of fruit and plenty of milk.” Sylvester expected meat three times a day. “He was a meat and potatoes man,” Lucile remembered.[50]

The Perkins family farm sat within the boundaries of the LDS Wilford Ward, organized in 1900. Martha came from a Latter-day Saint background on her mother’s side, but she had not been baptized as a child. Wilford Ward records show Martha joined the church in 1901, shortly after her marriage to Sylvester.[51] There is no indication that Sylvester was a baptized member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, but all of his children were baptized and confirmed as children and his wife remained a committed member all her life. She and the children appear on ward records and in church censuses. Sylvester was born to Mormon parents, raised by Latter-day Saints and associated with neighbors who belonged to the church. His daughter, Lucile, was a life-long member and in 1971, became the first Black Relief Society president of the newly formed Genesis Group.[52] However, LDS census records do not count Sylvester as a member. They stand as the most convincing evidence that he was not baptized into the faith.[53]

In March 1930, Martha’s father died in Idaho Falls, Idaho. On April 10, the census taker enumerated Martha living next door to her mother in that city.[54] She may have gone there to help after her father died. Sylvester and Martha’a youngest son, sixteen-year-old George, his grandfather’s namesake, was with her. Sylvester stayed in Salt Lake at his daughter and son-in-law’s home while Martha was in Idaho, thus accounting for the long-married couple appearing in census records in two different states.[55]

Four years later, on March 9, 1934, Sylvester died in Mill Creek. His funeral was conducted at the Ricketts Funeral Home in downtown Salt Lake City but his obituary does not name an officiator.[56] It may be significant that it was not held in the Wilford Ward or conducted by a Latter-day Saint bishop. He is buried at Elysian Burial Gardens in an unmarked grave.[57] If Sylvester was born in the mid-1850s, at the end of his life in 1934, he was one of the oldest persons still living who had been born enslaved in Utah Territory.[58]

By Tonya S. Reiter

With research assistance from Craig Patterson

[1] Sylvester’s mother’s name appears on some records as “Ester” and occasionally as “Estie.” Sylvester was likely the next to last child his mother bore. His sister Charlotte was probably born last.

[2] The record of Frank’s first baptism is lost, but he received a second baptism on November 27, 1875, in the Salt Lake Eighth Ward. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, microfilm 26,847, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] In 1875 when Mary Ann Perkins James, Sylvester’s sister, did proxy baptisms for deceased female relatives, she did not include a baptism for her mother. While this is not conclusive evidence, it might indicate Esther was a member of the church. See Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “Colored brethren and sisters, Endowment House, Salt Lake City, Utah, Sept, 3, 1875,” microfilm 255,498, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[4] Glen M. Leonard, A History of Davis County, (Utah State Historical Society, Davis County Commission: 1999), 22-23.

[5] Sylvester’s date of birth is uncertain because it varies from record to record. His age on his marriage certificate indicates his birth year could be 1859. His death certificate lists his birth year as 1868. If Esther was his birth mother, that is impossible because she would have been dead by that time. Later censuses do not help pin it down. His blessing record combined with his appearance in the 1856 Utah Territorial Census is convincing evidence that he was born in the 1850s.

[6] Utah Territory, 1856 Territorial Census, North Canyon Ward, MS 2929, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. Although the census of 1856 is notoriously unreliable and has entries for deceased people, it seems unlikely that the “Sylvester Perkins” listed with the rest of the Perkins family could be anyone other than this Sylvester, so he would have to have been born by the time the census was taken in February 1856.

[7] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, North Canyon Ward records, 1857-1890, microfilm 1,035,837, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[8] Christopher B. Rich, Jr, “The True Policy for Utah: Servitude, Slavery, and ‘An Act in Relation to Service,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 80, no. 1 (winter, 2012): 54-74 and W. Paul Reeve, Christopher B. Rich, Jr, and LaJean Purcell Carruth, This Abominable Slavery: Race, Religion, and the Battle over Human Bondage in Antebellum Utah (Oxford University Press, 2024).

[9] United States, 1860 Census, Slavery Schedule, Utah Territory, Davis County.

[10] They would have been emancipated by an act of Congress on 20 June 1862, but it is uncertain when Utah slaveholders actually informed enslaved people that they were legally free.

[11] Utah, Salt Lake County Death Records, 1849-1949, Esther Perkins, 20 December 1865, database and digital images, FamilySearch.org.

[12] United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City.

[13] Emma Russell, Footprints of Roy 1873-1979 (self-pub., 1979), 19.

[14] Luella Jones Durstin, “Richard G. Jones History,” FamilySearch Memories for Richard George Jones (KWNK-KFG), (accessed 7 August 2023).

[15] Sessions Settlement, Platt Map, Recorders Office, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[16] United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City 19th Ward.

[17] The US Censuses do not list Sylvester with the Jones family: United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Davis County, Bountiful; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Weber County, Hooper Precinct; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City 19th Ward.

[18] Rose and Ida Dalton, Roy, Utah Our Home Town (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1968), 223.

[19] Russell, Footprints, 19.

[20] Mary Lucile [Perkins] Bankhhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, Salt Lake County, Utah, 1985, transcript, 7, LDS Afro-American Oral History Project by the Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, MSS OH 824, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

[21] Luella Jones Dustin, “Richard G. Jones History,” FamilySearch Family Tree, Richard George Jones (KWNK-KFG), Memories, (accessed 18 Feb 2023).

[22] “Warm Springs Bath House P. 3,” Photo No. 7935, Utah State Historical Society, Classified Photographs. The identity of a young Black boy who is standing at the gate in an early photograph of the Warm Springs Bath House is not known, but might be Sylvester Perkins. The mule trolley pictured in the photo helps to date the picture to a time after 1870. There is a family memory associated with the first proprietors of the Warm Springs Bath House, Nineteenth Ward Bishop James Hendricks and wife, Drusilla, that mentions three Black people helping with the enormous workload at the facility. That reminiscence recounts a man named Bill, along with two women, Cad and Chloe, working for the Hendricks family. See Diane Hendricks, “The Hendricks Family at the Bath House in Salt Lake City 1848-1860,” FamilySearch Family Tree, James Hendricks (KWJD-NM1), (accessed 25 Aug 2023). Drusilla and James Hendricks ran the bath house in the early 1850s, likely twenty years before the picture was taken and there is no known connection between Bill, Cad, Chloe and Sylvester Perkins.

[23] Emma Russell, Footprints of Roy 1873-1979 (self-pub., 1979), 19.

[24] Luella Jones Dustin, “Richard George Jones,” FamilySearch memories for Richard George Jones KWNK-KFG.

[25] Dalton and Dalton, Roy, 12.

[26] Russell, Footprints, 19.

[27] The only records that remain for the North Kanyon Ward are the lists of baby blessings.

[28] Bankhead, interview by Alan Cherry, 7.

[29] Bankhead, interview by Alan Cherry, 4.

[30] Kate B. Carter, The Story of the Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1965), 30.

[31] Department of Agriculture and Food, Division of Animal Industry Brand books, Series 540, reel 1, Jun-Dec 1890, 7, Sylvester Purkins, Utah Division of Archives and Record Services, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[32] Bernice Gibbs Anderson, “Early Promontory,” in Golden Spike 95th Anniversary program 1869-1965, May 10, 1965, Promontory Summit, Box Elder County, Utah, typescript.

[33] Salt Lake County Recorder, Abstract Book B-9, page 54, line 13, Salt Lake County Recorder’s office, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[34] See: Tonya Reiter, “Life on the Hill: The Black Farming Families of Mill Creek,” Journal of Mormon History ,Vol. 44, No. 4 (October 2018), 68-89.

[35] Bankhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, 7.

[36] Utah, County Marriages, 1871-1941, Silvester Perkins and Martha Stevens, 1899.

[37] United States, 1900 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Mill Creek Precinct. According to family histories, Ben was Sylvester’s half-brother or adopted brother. Frank Perkins was thought to have had a wife before Esther and it is possible that she was Ben’s mother.

[38] Jack Beller, “Negro Slaves in Utah,” Utah Historical Quarterly vol 2 no 4, (October 1929), 125.

[39] Bankhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, 7.

[40] Bankhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, 8.

[41] Bankhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, 7.

[42] Bankhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, 4.

[43] Bankhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, 7.

[44] Mary Lucille[sic] [Perkins] Bankhead, oral interview by Leslie Kelen, Salt Lake City, Utah 1983, transcript, interview 1, 4. Interviews with Blacks in Utah, 1982-1988” Ms0453, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah. Mary Lucile’s name was spelled with one “L.”

[45] Bankhead, oral interview 1 by Leslie Kelen, 1-2.

[46] Bankhead, oral interview 1 by Leslie Kelen, 6.

[47] “Names Delegates to the Meeting of Negroes in Rural Pursuits,” Salt Lake Herald-Republican (Salt Lake City, Utah), 30 July 1915, 12. The newspaper article mentions a Mrs. Harriet Perkins as a delegate. There was no Black farmer by that name living in Salt Lake County at that time. It must be a garbled reference to Sylvester Perkins who was farming in Salt Lake County. All the other names can be identified.

[48] “Jury List for Coming Year,” Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah), 16 December 1905, 6.

[49] Kate B. Carter, The Story of the Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1965), 29.

[50] Bankhead, oral interview by Alan Cherry, 3.

[51] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Wilford Ward, part 1, 1907-1941, CR 375 8, box 7640, folder 1, image 41, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[52] “Mary Lucille [sic] Perkins Bankhead (1902-1994),” Black Members of the Church Research Guide, United States, (accessed 4 August 2023). The Genesis group was formed by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as an auxiliary for Black members.

[53] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church Census Records, Sylvester Perkins, 1914, 1920, 1925, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[54] United States, 1930 Census, Idaho, Bonneville, Idaho Falls, district 8.

[55] United States, 1930 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, district 35.

[56] “ Sylvester Perkins,” Salt Lake Tribune, (Salt Lake City, Utah) 11 March 1934, 23; Utah, State Board of Health, Certificates of Death, File No. 420, Sylvester Perkins, Utah Division of Archives and Record Services, Salt Lake City, Utah. Sylvester’s obituary lists his cause of death as stomach cancer, but his death certificate lists it as prostate cancer with metastasis.

[57] Sylvester Perkins, FindAGrave.com.

[58] Amy Tanner Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847-1862 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2022).

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.