Peter

Biography

Peter, or “Black Pete,” as he was known to his white neighbors in Kirtland, Ohio, was the first black person to affiliate in any way with the Mormon movement. Missionaries first reached northeastern Ohio in November 1830, and by February 1831, newspapers were already reporting that "Black Pete" worshiped with the Mormons and was considered a member of their company. There is, however, no known record of his baptism. [1]

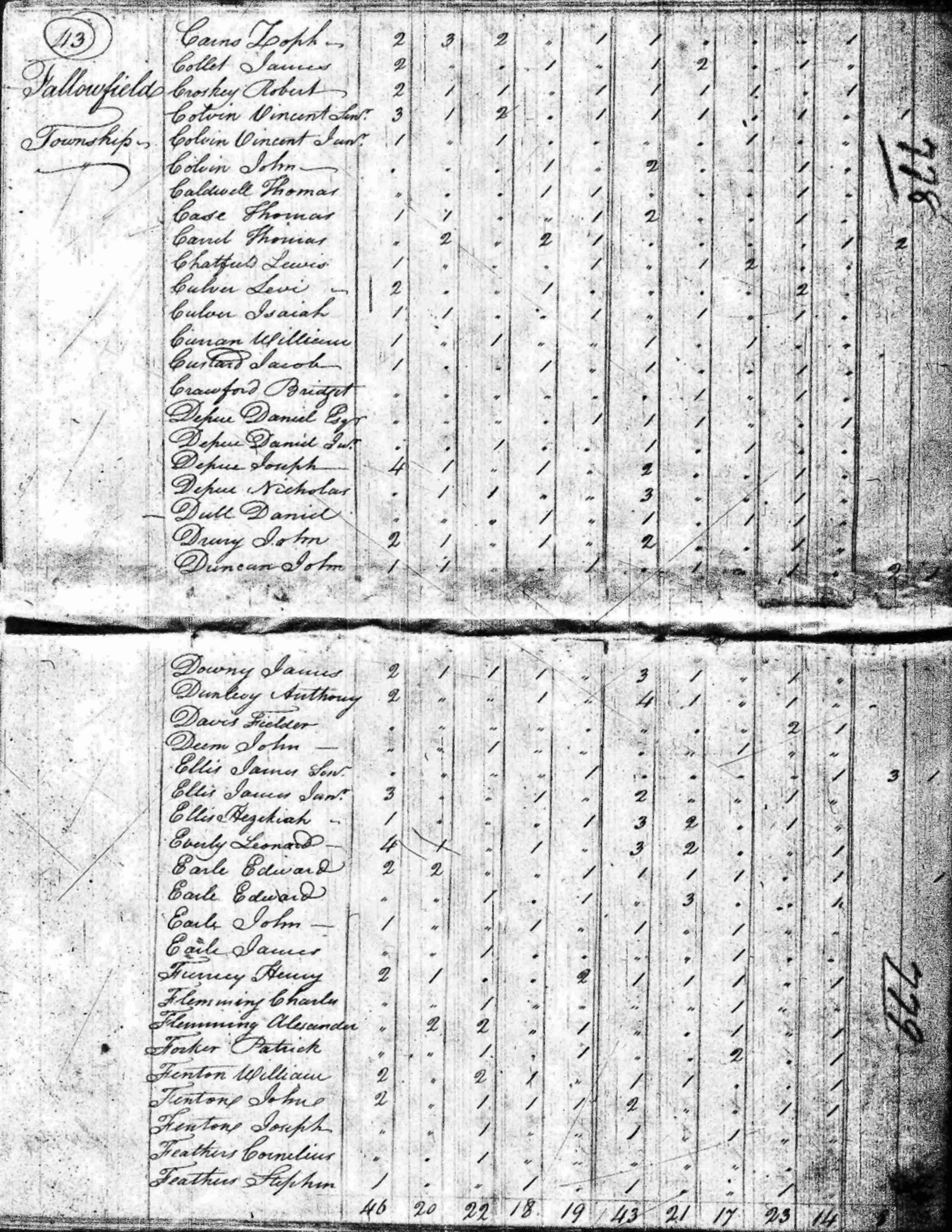

Peter was the child of a slave woman named Kino. [2] Born circa 1775, he grew up a slave in Fallowfield Township in western Pennsylvania. His enslaver, as of 1782 when Kino and her son Peter appear in the county’s slave register, was John Kerr Jr. Peter may have worked as a blacksmith or helped with farm labor.[3] Peter was born between four and five years too late to be eligible for early emancipation according to Pennsylvania’s gradual emancipation laws. [4] Thus, in 1894, Kerr willed Peter to his son Moses, who married Mary Carrel, and by 1800, Peter appears to have been a part of the household of Mary’s father Thomas Carrel.[5] In 1813, the Carrels and Kerrs moved to northeastern Ohio where slavery was illegal. In 1820, he was one of only six free blacks living in Geauga County, Ohio. [6] He appears to have taken up residence with John and Jemima Doan in Kirtland, Ohio. [7] By 1831, Peter had likely joined what was known as the “family,” a communal organization living on the Isaac Morley farm near Kirtland, patterned after the New Testament notion that Christian disciples should have “all things common” among them.[8]

The name "Black Pete" reflects common practices in naming enslaved people. The prefix “Black” was commonly prepended to slave names (Black Pete, Black Joe, and so forth), and most white people used the diminutive version of a slave’s Christian name (thus, Pete instead of Peter). His enslaver John Kerr Jr. sometimes called him Jack or John. [9] Some slaves assumed or were known by the surname of their owner, but no sources indicate "Black Pete" went by Peter Kerr or Peter Carrel. The earliest source simply names him Peter.[10]

Members of the Morley communal “family” converted to Mormonism en masse in late 1830 and early 1831, and Peter participated with them in worship services in the area. Among the circa 200 converts in the area, there was a group that was particularly attracted to ecstatic forms of worship, including shouting, singing, dancing, falling, and other activities they attributed to the workings of the Spirit. This group was composed largely of younger converts, but Peter, who was in his fifties, joined them in their worship. According to one observer, Peter was “made much of by them.”[11] He may have been influential on the worship practices of this group, importing elements of the shout tradition he may have been exposed to during his youth in Pennsylvania.[12]

Newspaper accounts describe this group engaging in a variety of practices, most of which were objects of the reporter’s ridicule. For example, they received purported revelations in the form of letters falling from heaven, acted out missions to American Indians, and spoke in unknown tongues. [13] The only account that says anything laudatory about Peter mentions that he was “a good singer.” [14] Mormon sources from the time period ignore Peter entirely.

Perhaps the most well-known story is that of Peter falling or jumping off a twenty-five-foot embankment into the Chagrin River. Non-Mormon sources lampoon this incident, suggesting that Peter thought he could fly. [15] George A. Smith suggested, however, that Peter was chasing an angel that was carrying a letter for him and perhaps inadvertently fell down the embankment. [16]

Several accounts used Peter to insinuate that Mormons were in favor of miscegenation. One mentioned that young Mormon women chased after Peter.[17] Some claimed that Peter said he received a revelation to marry a white woman, perhaps the daughter of Frederick G. Williams. [18]

Nothing is known of Peter’s activities after 1831. [19] The only known Mormon source that acknowledges him is George A. Smith’s 1864 sermon, but Smith spoke of "Black Pete" only in the context of the 1831 burst of enthusiasm in Ohio. Peter does not appear to have migrated to Mormon gathering places in Missouri in the mid-1830s. He may have parted ways with Mormonism after many of the ecstatic practices he engaged in were deemphasized. [20] It is also possible that Peter died shortly after his brush with Mormonism. He would have been sixty years old in 1835. [21]

By Matt McBride

Primary Sources

George A. Smith, Sermon, November 15, 1864, Ogden Tabernacle, George D. Watt Papers, MS 4534, Church History Library, transcribed by Lajean Carruth. Later published with significant revisions as George A. Smith, “Historical Discourse,” Deseret News, vol. 14, no. 12 (December 21, 1864) and George A. Smith, “Historical Discourse,” Journal of Discourses, George D. Watt, et al., eds., 26 vols. (London: Latter-Day Saints’ Book Depot, 1854–1886), 11:1-4.

“The Golden Bible or the Book of Mormon,” Ashtabula Journal 3, no. 10 (5 February 1831): 3. This item reproduces an article in the February 1,1831 Painesville Geauga Gazette. This article is also reproduced in full in the Hartford Connecticut Courant, July 12, 1831, 1.

“Mormonites,” The Sun (Philadelphia), August 18, 1831.

“Fanaticism,” Christian Register (Boston, Mass.), vol. 10 (March 26, 1831).

“Mormonism,” New England Weekly Review (Hartford, Conn.), vol. 6, no. 310 (February 17, 1834).

W. R. Hine, “W. R. Hine’s Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1888), 2.

Henry Carroll, “Henry Carroll’s Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 3.

H. W. Wilson, “Mrs. H. W. Wilson’s Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 3.

Reuben P. Harmon, “Reuben P. Harmon,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 1.

Joel Miller, “Joel Miller’s Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 2.

Washington County Virginia, Negro Register, 1782, 5.

United States Census, 1800, Fallowfield Township, Washington County, Pennsylvania.

United States Census, 1810, Fallowfield Township, Washington County, Pennsylvania.

United States Census, 1820, Kirtland Township, Geauga County, Ohio.

United States Census, 1820, Mentor Township, Geauga County, Ohio.

Last Will and Testament of John Kerr, Jr., September 8, 1794, Washington County Courthouse, 1:239–240.

Secondary Sources

Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People: The Historical Setting of Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations (Salt Lake City, Utah: Greg Kofford Books, 2009), 5–91.

W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 112–117.

Max Perry Mueller, Race and the Making of the Mormon People (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017), 87–89.

[1] Extant accounts of Black Pete’s involvement with Mormonism are inconclusive as to whether he was baptized or merely participated in Mormon worship services along with others living on or near the Morley farm. Mark L. Staker speculates, based on the nature of some reported ecstatic religious practices, that Black Pete was influential in the Mormon community for a short period and may have been ordained and assisted in preaching Mormonism to others in January 1831. Mark Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 74-86.

[2] Washington County Virginia, Negro Register, 1782, 5. Mark L. Staker suggests that Kino was of Mandinka heritage and was likely Muslim. See Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 7.

[3] Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 7.

[4] Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 6.

[5] Last Will and Testament of John Kerr, Jr., September 8, 1794, Washington County Courthouse, 1:239–240; United States Census, 1800, Fallowfield Township, Washington County, Pennsylvania; United States Census, 1810, Fallowfield Township, Washington County, Pennsylvania.

[6] Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 29.

[7] United States Census, 1820, Geauga County, Pennsylvania. See Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 31.

[8] Acts 2:44. This assertion is based on circumstantial evidence. See Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 31.

[9] Last Will and Testament of John Kerr, Jr., September 8, 1794, Washington County Courthouse, 1:239–240.

[10] Washington County Virginia, Negro Register, 1782, 5.

[11] “Henry Carroll’s Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 3.

[12] See Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People, 11–17.

[13] Jesse Jasper Moss, “Autobiography of a Pioneer Preacher,” M. M. Moss, ed. in Christian Standard, January 15, 1938, 10; “The Golden Bible, or the Book of Mormon,” Ashtabula Journal 3, no. 10 (5 February 1831): 3.

[14] “Joel Miller’s Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 1.

[15] “The Golden Bible or the Book of Mormon,” Ashtabula Journal 3, no. 10 (5 February 1831): 3; “Mormonites,” The Sun (Philadelphia), August 18, 1831; “Mormonism,” New England Weekly Review (Hartford, Conn.), vol. 6, no. 310 (February 17, 1834).

[16] George A. Smith, “Historical Discourse,” Deseret News, vol. 14, no. 12 (December 21, 1864). Though Smith’s account of this incident is much later, he was the LDS Church’s historian at the time of his sermon and had access to possible eyewitnesses such as Levi Hancock and Isaac Morley.

[17] Reuben P. Harmon, Statement, in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 1.

[18] “Henry Carroll’s Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 2 (April 1888), 3; “W. R. Hines Statement,” in Arthur B. Deming, ed., Naked Truths about Mormonism, Vol. 1, No. 1 (January 1888), 3.

[19] All free blacks in Ohio were required to register with their respective counties until the 1860s. One potential avenue of research would be to review these registers, many of which are extant. Unfortunately, they are scattered across the archives, courthouses, and historical societies of Ohio’s 88 counties.

[20] George A. Smith suggests many who were engaged in these practices “apostatized.” George A. Smith, “Historical Discourse,” 2.

[21] The life expectancy for white males at age twenty in the 1830s was approximately forty years. Most estimates suggest the expectancy for slaves and former slaves was about five years lower. See J. David Hacker, “Decennial Life Tables for the White Population of the United States, 1790–1900,” Historical Methods, vol. 43, no. 2 (April 2010), 45–79.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.