Ritchie, Nelson Holder

Biography

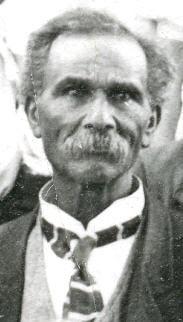

Nelson Holder Ritchie was a Black Mormon pioneer with a remarkable life story. His journey to Utah and into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints started in Missouri where he was born into slavery and from there to Kansas where he found liberty and safety at the home of abolitionist John Ritchie. He served in the Civil War, fighting on the side of freedom, and then built a successful business for himself at Great Bend, Kansas. By the 1890s, however, he suffered financial setbacks. Faith and a desire to rebuild economically led him and his family West where he was baptized in 1892. In 1909, however, he was denied permission to have his love for his wife “sealed” in an LDS temple because of his race. He nonetheless presided over a multi-generational family of Latter-day Saints, some of whom only discovered their racial history in the twenty-first century after DNA evidence revealed African ancestry. Those DNA results, combined with considerable historical sleuthing, led one of his descendants, Deena Porcaro Hill, to uncover the contours of Ritchie’s life story. Hill graciously shared sources, pictures, and her research with CenturyofBlackMormons so that Nelson Holder Ritchie could be named, numbered, and remembered here.

In April 1891, when William C. Mann, a missionary for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, from Bountiful, Utah, first met Nelson Holder Ritchie in Great Bend, Kansas, Mann described Ritchie as “a dark man” who “dont belong to the church but he treats us veary kind.” In contrast, Mann described Nelson’s wife, Annie Cowan Russell, as “a white lady and she belongs to the church.” [1] Mann’s two initial impressions thus centered on race and religion, both of which were more complicated than Mann was aware of at the time.

Annie had been baptized the year before, a likely convert from the Church of Jesus Christ (Bickertonite), a divergent faith in the Latter-day Saint tradition which grew out of the succession crisis following the death of Joseph Smith in 1844. [2] Sidney Rigdon, Smith’s counselor in the governing First Presidency, claimed to be Smith’s true successor and attracted followers; William Bickerton was one of those followers who dissented from Rigdon and formed his own movement. [3] In 1875, Bickerton established a religious colony in Kansas which he called Zion Valley and which was later renamed St. John. [4] Annie moved to Kansas with followers of Bickerton and helped to found Zion Valley. In fact, her wedding in 1876 to Nelson Holder Ritchie took place in Zion Valley and, following the ceremony, Eli Kendall, a follower of Bickerton, hosted “one of the most sumptuous feasts ever held in the county” for the newlyweds. [5] In any case, Mann later rebaptized Annie into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on 17 November 1892, the same day that he baptized Nelson, after the couple had migrated to Utah. [6]

Nelson Holder Ritchie’s racial identity was also more complicated than Mann’s journal entry described. Mann referred to Nelson as “a dark man,” but offered no additional details and never mentioned his appearance or referred to racial matters after that. Other documents tell a complex racial story. When Ritchie registered for the Civil War draft in Topeka, Kansas in 1863, the registrar listed him as “colored.” [7] Two years later, the Kansas state census described him as “black,” while the 1870 federal census called him “mulatto.” [8] In 1870, he was elected secretary of a “colored citizens” meeting which convened at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Topeka, in an effort to get out the vote. [9] He was “colored” in the 1875 Kansas census and “mulatto” again in the 1880 federal census. [10] The 1885 Kansas census, however, defined him as “white,” as did the 1900 federal census, this time taken in Utah. [11] Finally, in 1910, the last year he appeared in a census record, the census taker listed him as “Indian.” [12] His death certificate three years later called him “white.” [13]

Although some Ritchie descendants do find Native American ancestry in their DNA, a greater degree of African ancestry prevails. Nelson Holder Ritchie was most likely the son of a yet unidentified black enslaved woman and a white man named Wiley Holder. As of August 2018, seventy-two of Nelson Holder Ritchie’s descendants have had DNA tests performed through Ancestry.com. Thirty-seven descendants of the George Vincent Holder family of Cumberland and Harnett County, North Carolina have also submitted DNA for analysis. So too have seventy-three descendants of Sarah and Sherod (or Sherd) McNeill, an enslaved couple also from Cumberland and Harnett County, North Carolina. The results of these various DNA studies reveal that the white Latter-day Saint descendants of Nelson Holder Ritchie are genetically related to the white descendants of George Vincent Holder. They also reveal that the white Latter-day Saint descendants of Nelson Holder Ritchie are genetically related to the African-American descendants of Sarah and Sherod McNeill. [14]

Circumstantial and primary source evidence, when combined with DNA evidence, offer important clues into Nelson’s parentage. Those combined sources suggest that George Vincent Holder’s son Wiley visited his Uncle, William Holder, in November 1839, and there encountered the enslaved daughter of Sarah and Sherod McNeill. [15] Although it is impossible to determine the nature of that meeting, Wiley would have been twenty-seven years old at the time and the enslaved woman would have been around nineteen. Wiley was white and free and she was black and enslaved. The unequal power dynamics and absence of evidence of any long-term relationship suggest a lack of consent, a tragic part of life for enslaved women in the plantation South.

William Holder, Wiley’s uncle, was the only enslaver in the Holder family but was financially strapped by 1840. Circumstantial evidence suggests that he sold the enslaved woman, now pregnant, to Neal McNeill, a former neighbor who was then visiting from Lawrence County, Missouri. McNeill took the pregnant enslaved woman back to Missouri where she gave birth to Nelson Holder on 28 August 1840. Tragically Nelson’s mother died shortly thereafter. [16] Later in life, two of Nelson’s daughters recalled their dad explaining that he was mostly raised by “an old Scotch woman.” [17] In 1909, Nelson identified that Scottish woman as Nancy McNeill, the mother of Neal McNeill, who was indeed an immigrant from Scotland. She was a next-door neighbor to her slave holding son according to the 1850 census, a fact which adds credibility to Nelson’s recollection. [18] In addition, when Nelson received a patriarchal blessing in 1912 (a formal blessing in the Latter-day Saint tradition which is written and preserved), the scribe who recorded that blessing listed Nelson’s basic biographical information as Nelson dictated it. The scribe wrote Nelson’s father’s name as “Riley” Holder, an easy phonetic mishearing of “Wiley.” [19] DNA evidence thus indicates that one of George Vincent Holder’s sons was Nelson’s father and corroborating evidence suggests that that son was Wiley.

Other documents also help to build the case regarding Nelson’s early years, although not always exactly. The 1850 census slave schedule for Neal McNeil, for example, lists a ten-year-old “mulatto” among McNeill’s enslaved population. The census taker, however, recorded the gender of that ten-year-old as female. All of the other identifying information matches what we might expect Nelson Holder’s profile to be: he was ten in 1850 and he would have been mulatto according to racial classifications of the time. In addition, the ten-year-old was the only enslaved person listed in McNeil’s possession who was described as “mulatto;" the rest of his enslaved people were listed as “black.” The only detail that does not match is the gender—a mistake that is not atypical in census records. [20] In sum, there is not much that is knowable about Nelson’s early life, but considerable evidence does indicate that he was born into slavery. After his mother’s death he was raised by Nancy McNeill, his enslaver’s mother.

Existing documents do not mention Nelson by name until he was twenty-three years old. In 1863, his name first enters the written record when he registered for the Civil War draft. By that point he was living in the home of a prominent Kansas abolitionist named John Ritchie who operated a known safe house on the underground railroad. [21] There is no surviving evidence to indicate how Nelson arrived there or exactly how he gained his freedom. Nonetheless, he adopted the last name of Ritchie as sure evidence of the bond he felt toward the man who gave him shelter. Nelson then served in Company B of the 2nd Kansas State Militia and fought in the Battle of the Blue, a successful effort to repel a Confederate raid of Missouri in October 1864. [22]

Following the war Nelson married Mary Mathews Fulbright on 26 May 1870, in Topeka, with a pastor from the Methodist Episcopal Church performing the ceremony. The couple had one child together, a boy who they named John Eddie. [23] Tragically he and Mary Mathews died within a year of the birth. Sometime later Nelson met Annie Cowan Russell whom he married on 21 December 1876, a woman he called his “dove” and to whom he remained married for the rest of his life. They had twelve children together, nine of whom survived into adulthood. [24]

Economically Nelson struck out on his own and through hard work, a keen financial sense, and perseverance, he rose to prominence. He became an important business owner at Great Bend, Kansas where he operated the Union Hotel along with a livery stable and a dray and hack service which ran between the town and railroad. Nelson advertised his business ventures in the Great Bend Tribune and noted that his hacks ran “to and from all trains” and his drays “to and from the depot and all parts of the city.” [25] Hacks were horse drawn carriages with roofs and seats for passengers but with open sides, while drays were more like wagons and typically carried cargo. Nelson also ran omnibuses in Great Bend which were enclosed passenger cars which looked like a streetcar or trolley except pulled by horses. In 1876, the Tribune called Nelson’s new omnibus “a grand enterprise for our city.” [26]

By the mid-1880s, Nelson enjoyed considerable success. In December 1885, the Great Bend Tribune bragged that “Ritchie’s hotel is having a fine business and promises to have all it can do.” [27] Yet signs of trouble also sometimes appeared in the paper. In 1883, he sold twenty-six head of cattle for $600 which meant that he did not need to follow through on a planned property sale. He felt good that “he has his financial matters fixed up.” [28] The real problems began, however, in 1888 when a fire in the kitchen of Nelson’s hotel spread and destroyed the entire west end of the building. The Barton County Democrat called it “a total wreck.” The bedding and carpets and other fixtures in the upper rooms were destroyed along with the kitchen and pantry fixtures. Even still firefighters were successful in stopping the fire before it destroyed the main part of the building and the newspaper did note that Ritchie was insured. [29] Within three months the Democrat announced that the “old Union hotel, which was nearly burned down some months ago, has been again repaired and put in shape for business.” [30]

Nonetheless, problems persisted. When LDS missionary William C. Mann first met the Ritchies in April 1891, he wrote that Nelson was “poor.” He and his companion, Willard Richard Johnson, each agreed to pay one dollar per week for a room and “grub” at the hotel. In May, Mann recorded that “Mr. Ritchie lost his streetcar business” and that it had “drop[p]ed into other hands.” [31] In October of that year, Nelson traveled to Oklahoma and sold some of his livery stock. [32] He also looked into the possibility of claiming land with the Cherokee Nation based on his assertion of Native American ancestry, but he returned to Great Bend disappointed in that prospect and decided against it. [33]

In the meantime, William Mann and his companion Willard Johnson continued to cultivate a friendship with the Ritchies. They helped Nelson and Annie with work at the hotel and livery stables as well as repaired fences and unloaded hay. [34] On September 13, 1891, Annie Ritchie had Mann and Johnson bless her four youngest children, Elizabeth, Annie May, Blanch, and Esther, at a church conference in St. John. Just two days later, the same missionaries baptized the two oldest children, Olive and James Alvie, also at St. John. [35]

As the Ritchie family strengthened their ties to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and to William Mann, the missionary who taught them its precepts, Nelson’s financial ties to Great Bend weakened and Utah started to look increasingly attractive as a place for Nelson to start a new life, both spiritually and economically. [36] By September 1892, Nelson had sold his omnibus line, leased his barn, and the Great Bend Tribune noted on the twenty-third of that month that “Ritchie has left the city and gone to Utah.” [37]

Nelson never did regain his financial footing after moving to Utah. He farmed and ranched and peddled fruit and the family moved frequently. They lived in Bountiful, Centerville, Salt Lake City, Orem, Sugar House, and Parley’s Canyon. In the 1900 census Nelson listed his occupation as a fruit peddler and in 1910 he called himself a laborer at “odd jobs.” [38]

The family nonetheless maintained a close relationship with William C. Mann and perhaps their social integration was more successful than Nelson’s efforts to rebuild economically. Shortly after the family arrived in Utah, Nelson, Annie, James Alvie, and possibly Olive, went to Beck’s Hot Spring, north of Salt Lake City, and on 17 November 1892, William C. Mann baptized them. It was a rebaptism for James Alvie and possibly Olive, but it was Nelson’s first baptism and likely Annie’s too. [39]

Nelson remained a committed Latter-day Saint for the remainder of his life. Each time the family moved, their LDS membership records were promptly transferred to their new congregation—evidence that the family continued to practice their faith. The Ritchie family stayed in the Sugar House ward the longest, from 1905 to 1912. The ward then split and their records were transferred to the newly formed Parley’s Ward. [40]

It was in the Sugar House Ward, in 1909, that Nelson and Annie approached their bishop, John M. Whitaker, to request temple admission so that they could be sealed to each other for eternity. Unfortunately, neither Annie or Nelson left a written account of that experience but Bishop Whitaker did. As Whitaker recalled, on 10 December, Nelson visited Whitaker in his home. Nelson “came for a recommend to go through the temple,” Whitaker wrote. It was “a long conversation” in which Whitaker “asked many questions concerning his birth.” Nelson described his father as “a pure blooded Cherokee Indian” and said “he never knew his mother, but was told by some friends she was very dark, Creole or mulatto.” Nelson also explained that “a woman by the [name] of Nancy McNeal raised him.” Nelson reported that he had told Annie “all he knew of his genealogy” before he married her and that they now “want to go through the temple.” [41]

Whitaker admitted that Nelson had been a “faithful and a good provider” and that he “saw no reason why he could not” go through the temple, except for one problem: “As soon as [Nelson] crossed the thresh hold of the front door, I felt that he had negro blood in him,” Whitaker claimed. That “feeling still persisted” for Whitaker. He had subsequent conversations with Nelson and he eventually interviewed Annie in order to learn “all the facts she knew,” yet he still “felt the same.” [42]

Nelson and Annie “were really disturbed over the matter.” Whitaker thus resolved to “take their genealogy and all the facts and submit the case to the First Presidency of the Church.” Whitaker claimed that the First Presidency “held several meetings” on the case, including some meetings with the quorum of twelve apostles. Eventually Joseph F. Smith, then president of the church, instructed Whitaker that he was a “common Judge in Israel” and left the decision in his hands. [43]

Whitaker called it a “terrible responsibility” and again met with Annie and Nelson on several occasions as he contemplated his decision. Whitaker finally told the Ritchies that he “appreciated they were good saints” but “feeling as I did, I dare not issue a recommend to the temple unless my feeling changed.” He explained that “according to my understanding of the gospel anyone with Negro Blood was not entitled to the temple rights.” In response, Nelson and Annie pointed out the inconsistency in that policy, given the fact that at least some of their children “had already been to the Temple for their marriage.” [44]

Whitaker refused to budge. He told Annie and Nelson “to be faithful and no one could eventually hinder them from receiving all blessings earned by them.” He also explained that his decision was not motivated by “any personal feelings,” but rather by a personal conviction that he “must not go against” his “continued impressions.” In a moment of introspection Whitaker even claimed responsibility “for anything I did to hinder good people from going to the temple.” He called the case “a source of considerable sorrow” to him because, he said, “I believe they were good saints.” Nonetheless, he “never gave the recommend.” [45]

Nelson received his patriarchal blessing in 1912 and continued his devotion as a Latter-day Saint. He passed away on the 28 January 1913 in Sugar House of arteriosclerosis, or hardening of the arteries, and old age. He was 72 years old. [46] The Salt Lake Tribune, the Salt Lake Herald, and the Davis County Clipper all ran stories on his death and funeral. [47] The Herald called him a “well known and popular figure” in Salt Lake County. His daughter Grace recalled that at his funeral the “church was so full no more could get in it”. William Mann and Nelson’s former bishop, John Whitaker, both spoke at the service. Nelson was then laid to rest in the Bountiful City Cemetery in Davis County, next to his son Nelson Jr., who had died there in 1896 when he was two years old. [48]

Nelson’s wife Annie lived another thirty-seven years after her husband passed away. Perhaps she and her children took Bishop Whitaker’s council to heart, that in their faithfulness “no one could eventually hinder them from receiving all blessings earned by them.” LDS Church policy attempted to prohibit people of black African descent from receiving priesthood ordinations and temple rituals, even by proxy after death. Yet the Ritchie family itself proved how impossible it was to police such a policy among the living, let alone among the dead. Nelson and Annie had twelve children, nine of whom survived to adulthood. The nine children who lived past age eight were baptized as Latter-day Saints and all of them received their priesthood and temple rituals before June 1978, either in life or by proxy after death. By the time Annie was eighty-four, she had seventy-seven living descendants, all of whom would have had much more than “one drop” of African ancestry. [49] Yet many of those seventy-seven descendants (and the generations that followed) participated in priesthood and temple rituals before the June 1978 revelation lifted the prohibition. They did so with no knowledge of the events of 1909 which had blocked their pioneer forefather from being sealed to his wife. [50]

Like his posterity, Nelson Holder Ritchie did not have to wait until 1978 either. Likely at Annie’s instigation, or at the insistence of one of their children, Nelson was given the priesthood by proxy in the Salt Lake City Temple in 1923, and the endowment ritual on the same day. Annie then had Nelson sealed to her by proxy in 1924, also in the Salt Lake City Temple, thus proving Bishop Whitaker correct--no one could hinder her from receiving all of the blessings of the faith which she held so dear. [51]

By W. Paul Reeve

Primary Sources

“A Serious Runaway.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 2 February 1883, 4.

Ashton, Grace Ritchie. “An edited history of Nelson Holder Ritchie (1840–1913), written in 1975 by a daughter, Grace Ritchie Ashton.”

“A Young Child of N. H. Richie.” Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas). 3 July 1890.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Farmers Ward, CR 375 8, box 4049, folder 1, image 199. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Parleys Ward. CR 375 8, box 5238, folder 1, image 32; box 5239, folder 1, image 33. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Sugar House Ward. CR 375 8, box 6743, folder 1, image 469. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Record of Members Collection. Timpanogos Ward. CR 375 8, box 5087, folder 1, image 57. Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Consolidated Lists of Civil War Draft Registrations, 1863-1865. Records of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau (Civil War). Record Group 110. National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

“Deaths.” Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah). 31 January 1913, 11.

“Death Suddenly Calls Nelson H. Ritchie.” Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah). 29 January 1913, 10.

“Delegates and Their Alternates.” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 3 October 1878, 2.

“Delinquent Tax List.” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 2 September 1890.

“Died,” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 29 July 1880, 3.

“Great Bend Building and Loan.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 9 March 1888.

Hill, Deena Porcaro. “Annie Cowan Russell and her connection to William Bickerton and the Church of Jesus Christ,” 20 March 2018.

“Hotel for Sale.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 5 June 1885.

Kansas. Barton County. Marriage License. Nelson H. Ritchie to Anna Rusell. 21 December 1876.

Kansas. Shawnee County, Topeka. Marriage License. Nelson H. Ritchie to Mary Mathews Fullbright, 26 May 1870.

Kansas State. 1865 Census. Shawnee County, Topeka.

Kansas State. 1875 Census. Barton County, Great Bend.

Kansas State. 1885 Census. Barton County, Ellinwood.

“Legal.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 21 September 1884.

“Livery Stables.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 6 May 1887.

“Lock Your Doors.” Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas). 21 November 1889.

Mann, William C. Mission journal. MS 26229. Church History Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

“M. E. Church in Great Bend.” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 24 January 1878, 2.

“Meeting of Colored Citizens.” Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, Kansas). 3 April 1870, 4.

“Mother of Big Family to Celebrate 87th Birthday.” Davis County Clipper (Woods Cross, Utah). 10 March 1944, 8.

“Mr. Richie Bought the Southern Hotel.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 12 June 1885.

“Mr. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 3 August 1883.

“Mr. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 21 December 1888.

“Mr. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 22 May 1891.

“Mrs. N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 5 September 1890.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Atchison Daily Champion (Atchison, Kansas). 12 April 1873.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 10 May 1883, 3.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 19 November 1874, 4.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 22 September 1892, 3.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 11 January 1879.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 2 September 1892.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 18 September 1890.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 23 September 1892.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 15 April 1892, 3.

“N. H. Ritchie.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 23 October 1891.

“N. H. Ritchie.” St. John Daily Capital (St. John, Kansas). 18 March 1887, 4.

“N. H. Ritchie has Sold his Bus Line.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 2 September 1892.

“N. H. Ritchie.” The Larned Eagle-Optic (Larned, Kansas). 27 August 1886, 3.

“Nelson H. Ritchie Dies at Seventy-Two.” Davis County Clipper (Woods Cross, Utah). 31 January 1913, 1.

“On Monday.” Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas). 23 August 1888.

“Order Rebated.” Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas). 21 April 1892.

“Publication Notice.” St. John Weekly News (St. John, Kansas). 27 September 1888, 4.

“Real Estate Transfers.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 15 April 1887.

“Richie-Russell.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 30 December 1876.

“Richie’s Omnibus Line!” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 14 March 1884.

“Richies new Bus.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 12 August 1876.

“Ritchie Funeral Today.” Salt Lake Herald (Salt Lake City, Utah). 30 January 1913, 3.

“Ritchie’s Hotel.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 25 December 1885.

Rogers, Bessie Ritchie. “History of Bessie Ritchie Rogers.”

“S. Tullis.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 19 March 1886, 4.

Scales, Joseph A. Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, to Nelson Holder, Great Bend, Kansas, 24 May 1892.

“Sheriff’s Sale.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 4 August 1877, 1.

“Sheriff’s Sale.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 5 February 1879.

“The Bus Men.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 7 May 1886.

“The Chief of the Sax and Fox.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 8 January 1892.

“The Council Located.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 13 May 1892.

“The Courts.” The Weekly Commonwealth (Topeka, Kansas). 24 February 1887.

“The Latest Fire.” Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas). 31 May 1888.

“The Old Ritchie Barn.” Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas). 1 September 1892.

“The Old Southern Hotel.” Great Bend Register (Great Bend, Kansas). 11 June 1885, 3.

“The Old Union Hotel.” Barton County Democrat (Great Bend, Kansas). 23 August 1888.

“The Center of Section 28.” Great Bend Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 9 August 1911.

“Thursday.” Great Bend Weekly Tribune (Great Bend, Kansas). 25 March 1892.

Topeka, Kansas. City Directory, 1868 and 1870.

United States. 1850 Census. Missouri, Lawrence County, District 47.

United States. 1850 Census. Slave Schedule. Missouri, Lawrence County, District 47.

United States. 1870 Census. Kansas, Shawnee County, Topeka.

United States. 1880 Census. Kansas, Barton County, Great Bend.

United States. 1900 Census. Utah, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City.

United States. 1910 Census. Utah, Salt Lake County, Sugar House.

Utah. State Board of Health. Death Certificate. File No. 146. Registered No. 139. Nelson Holder Ritchie. Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Whitaker, John Mills. Memorandum from the daily journal of John M. Whitaker (December 1906 to March 1912). Typescript of transcripts from John M. Whitaker journal. J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Secondary Sources

Bell, Jeff. “The 2nd Kansas State Militia and the Battle of the Blue.”

Entz, Gary R. "The Bickertonites: Schism and Reunion in a Restoration Church, 1880–1905," Journal of Mormon History 32 (fall 2006): 1–44.

Entz, Gary R. “Zion Valley: The Mormon Origins of St. John, Kansas,” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 24 (Summer 2001): 98-117.

“Freedom's Struggle: The Ritchie House.”

Hill, Deena Porcaro. “The Surmise of the life of Nelson Holder Ritchie.” 08 June 2016, revised August 2018.

Quinn, D. Michael. “The Mormon Succession Crisis of 1844,” BYU Studies 16 (Winter 1976): 187-233.

Ritchie, Nelson Holder. FindAGrave.com.

Ritchie, Nelson Holder Jr. FindAGrave.com.

Ritchie, Nelson Holder. (KWCG-6BN). Ordinance records on familysearch.org (accessed 9 January 2019).

Stone, Daniel P. William Bickerton: Forgotten Latter Day Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2018).

[1] William C. Mann, mission journal, MS 26229, 99-100, Church History Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[2] On the succession crisis see D. Michael Quinn, “The Mormon Succession Crisis of 1844,” BYU Studies 16 (Winter 1976): 187-233.

[3] On Bickerton see Daniel P. Stone, William Bickerton: Forgotten Latter Day Prophet (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2018).

[4] On the move to Kansas and Bickerton’s history there see Gary R. Entz, “Zion Valley: The Mormon Origins of St. John, Kansas,” Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 24 (Summer 2001): 98-117; and Gary R. Entz, "The Bickertonites: Schism and Reunion in a Restoration Church, 1880–1905," Journal of Mormon History 32 (fall 2006): 1–44.

[5] “Richie-Russell,” Great Bend Tribune, 30 December 1876; Kansas, Barton County, Marriage License, Nelson H. Ritchie to Anna Rusell, 21 December 1876; Deena Porcaro Hill, “Annie Cowan Russell and her connection to William Bickerton and the Church of Jesus Christ,” 20 March 2018. Her father was a member of the Salt Lake City based LDS Church so it is possible that Annie was too.

[6] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Sugar House Ward, CR 375 8, box 6743, folder 1, image 469, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[7] Consolidated Lists of Civil War Draft Registrations, 1863-1865 , Records of the Provost Marshal General’s Bureau (Civil War), Record Group 110, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington D.C.

[8] Kansas State, 1865 Census, Shawnee County, Topeka; United States, 1870 Census, Kansas, Shawnee County, Topeka.

[9] “Meeting of Colored Citizens,” Daily Commonwealth (Topeka, Kansas), 3 April 1870, 4.

[10] Kansas State, 1875 Census, Barton County, Great Bend; United States, 1880 Census, Kansas, Barton County, Great Bend.

[11] Kansas State, 1885 Census, Barton County, Ellinwood; United States, 1900 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City.

[12] United States, 1910 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Sugar House.

[13] Utah, State Board of Health, Death Certificate, File No. 146, Registered No. 139, Nelson Holder Ritchie, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[14] Deena Porcaro Hill, “The Surmise of the life of Nelson Holder Ritchie,” 08 June 2016, revised August 2018.

[17] Grace Ritchie Ashton, “An edited history of Nelson Holder Ritchie (1840–1913), written in 1975 by a daughter, Grace Ritchie Ashton” (accessed 9 January 2019); Bessie Ritchie Rogers, “History of Bessie Ritchie Rogers,” (accessed 9 January 2019).

[18] United States, 1850 Census, Missouri, Lawrence County, District 47.

[19] For the biographical information on Nelson’s patriarchal blessing see Deena Porcaro Hill's blog post here (accessed 9 January 2019).

[20] United States, 1850 Census, Slave Schedule, Missouri, Lawrence County, District 47.

[21] Topeka, Kansas, City Directory, 1868 and 1870. In these two city directories Nelson is living at John Ritchie’s home. In 1868 he is listed as “colored” and in both directories his occupation is “teamster.” For John Ritchie and his home on the underground railroad see “Freedom's Struggle: The Ritchie House” (accessed 9 January 2019).

[22] For additional information on the 2nd Kansas State Militia and its Civil War service see Jeff Bell, “The 2 nd Kansas State Militia and the Battle of the Blue.”

[23] Kansas, Shawnee County, Topeka, Marriage License, Nelson H. Ritchie to Mary Mathews Fullbright, 26 May 1870.

[24] Kansas, Barton County, Marriage License, Nelson H. Ritchie to Anna Rusell, 21 December 1876.

[25] “N. H. Ritchie,” Great Bend Tribune, 11 January 1879.

[26] “Richies new Bus,” Great Bend Tribune, 12 August 1876.

[27] “Ritchie’s Hotel,” Great Bend Tribune, 25 December 1885.

[28] “N. H. Ritchie,” Great Bend Register, 10 May 1883, 3.

[29] “The Latest Fire,” Barton County Democrat, 31 May 1888.

[30] “The Old Union hotel,” Barton County Democrat, 23 August 1888.

[31] Mann, mission journal, 108.

[32] “N. H. Ritchie,” Great Bend Weekly Tribune, 23 October 1891.

[33] “Thursday,” Great Bend Weekly Tribune, 25 March 1892; “N. H. Ritchie,” Great Bend Weekly Tribune, 15 April 1892, 3; Joseph A. Scales, Cherokee Nation, Indian Territory, to Nelson Holder, Great Bend, Kansas, 24 May 1892. See also, “The Chief of the Sax and Fox,” Great Bend Weekly Tribune, 8 January 1892. Nelson’s daughter Grace wrote of the experience this way: “Before they left Kansas, Father received a letter from the government telling him he could go to Oklahoma to take up 160 acres of land for each of his children, also himself and his wife. Father went down there to look it over, and when he came back he told Mother that that was no place to take a family to raise.” Grace Ritchie Ashton, “An edited history of Nelson Holder Ritchie” (accessed 9 January 2019).

[34] Mann, mission journal, 100, 101, 105, 111, 114, 126, 131, 132, 160.

[35] Mann, mission journal, 158-159.

[36] Mann, mission journal, 155. It was on 3 September 1891 that Mann wrote, “Mr. Ritchie asked a few questions on the Gospel this evening and we answered the same.”

[37] “N. H. Ritchie,” Great Bend Tribune, 23 September 1892; “The Old Ritchie Barn,” Barton County Democrat, 1 September 1892; “N. H. Ritchie has sold his bus line,” Great Bend Tribune, 2 September 1892.

[38] United States, 1900 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City; United States, 1910 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Sugar House.

[39] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Sugar House Ward, CR 375 8, box 6743, folder 1, image 469, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. Unfortunately, researchers have not yet found the original baptismal record to verify if Olive was rebaptized with James Alvie. Their sister Bessie remembered that Olive was there and was rebaptized that day, but no record has yet been found to verify that claim. It is not clear where the family lived at the time of the baptism. Bessie later recalled that when the family arrived in Utah they, “stopped at the old Valley House where the Greyhound station now is. We then went to East Bountiful to Elder William C. Mann’s until we could get a house to live in.” There is no record of the baptisms in the East Bountiful membership records, but William C. Mann’s records are found there. One news account in the Davis County Clipper commemorated Annie’s eighty-seventh birthday and reported that the family moved to Utah in 1892 “and settled in Salt Lake, latter moving to Bountiful.” If the family indeed lived in the old “Valley House” in Salt Lake City after arriving in Utah as Bessie recalled or “settled in Salt Lake” as the Clipper reported then their baptisms were likely recorded in the yet unfound Salt Lake City ward where they lived before moving to Bountiful. See Rogers, “History of Bessie Ritchie Rogers,” and “Mother of Big Family to Celebrate 87th Birthday,” Davis County Clipper, 10 March 1944, 8.

[40] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Timpanogos Ward, CR 375 8, box 5087, folder 1, image 57; Farmers Ward, CR 375 8, box 4049, folder 1, image 199; Sugar House Ward, CR 375 8, box 6743, folder 1, image 469; Parleys Ward, CR 375 8, box 5238, folder 1, image 32; Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[41] John Mills Whitaker, Memorandum from the daily journal of John M. Whitaker (December 1906 to March 1912), typescript of transcripts from John M. Whitaker journal, 150, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[42] Whitaker, Memorandum, 150.

[43] Whitaker, Memorandum, 150.

[44] Whitaker, Memorandum, 150.

[45] Whitaker, Memorandum, 150-151.

[46] Utah, State Board of Health, Death Certificate, File No. 146, Registered No. 139, Nelson Holder Ritchie. Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[47] “Death Suddenly Calls Nelson H. Ritchie,” Salt Lake Herald , 29 January 1913, 10; “Ritchie Funeral Today,” Salt Lake Herald, 30 January 1913, 3; “Nelson H. Ritchie Dies at Seventy-Two,” Davis County Clipper, 31 January 1913, 1; “Deaths,” Salt Lake Tribune, 31 January 1913, 11.

[48] Ashton, “An edited history of Nelson Holder Ritchie.” For Nelson Holder Ritchie, Jr.’s burial see his memorial at FindAGrave.com. Nelson Holder Ritchie’s memorial is also available at FindAGrave.com.

[49] “North Salt Lake Woman Boasts 77 Living Descendants,” undated newspaper clipping as found here (accessed 9 January 2019).

[50] Nelson Holder Ritchie (KWCG-6BN), ordinance records on familysearch.org (accessed 9 January 2019).

[51] Nelson Holder Ritchie (KWCG-6BN), ordinance records on familysearch.org (accessed 9 January 2019).

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.