Wales, Hark

Biography

The life of Hark Wales (known as Hark Lay before gaining his freedom) was marked by events which many African Americans experienced in the years surrounding the Civil War: the transition from enslavement to freedom, the creation of a community in a new landscape, and the effort to achieve economic independence after emancipation. In addition, Wales’ role as an 1847 pioneer into the Salt Lake Valley makes him an important figure in the history of Utah and the westward migration of the Latter-day Saints.[1]

Born enslaved around 1825 in Monroe County, Mississippi, on the plantation of southern planter John Crosby, Wales grew up in bondage. His childhood and adolescence were shaped by the demands of slave labor. When John Crosby died in 1841, his probate inventory valued the sixteen-year-old Wales at $550. In the ensuing settlement of Crosby’s estate, his twenty-four enslaved people were divided among his surviving family members with Crosby’s daughter Sytha and her husband William Lay inheriting Wales. He thus became known as Hark Lay even though he would later choose Wales as his surname once freed.[2]

Within a year of the settlement of the Crosby estate, missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints passed through the region. Some members of the Crosby family converted in late 1843 and formed a core group of believers in the area. They were soon organized into a small congregation called the Buttahatchy Branch with William Crosby, Sytha’s brother, ordained as “presiding elder.” When missionary John Brown visited the group in December 1843, he wrote that fellow missionaries James Brown and Peter Haws had organized the branch “a short time before” and that it included “some 15 or 16 members, all newly baptized.” Unfortunately, Brown did not specify the names of the branch members, so it is impossible to know if Wales was among them.[3]

Wales’ enslaver Sytha Lay was baptized in April 1844, but her husband William did not convert.[4] It is possible that Wales was baptized around the same time. A belated Crosby family remembrance suggested that he was baptized at a place called Mormon Springs in Monroe County but baptismal records do not survive to substantiate that claim.[5] The best evidence for Wales’ LDS membership comes from a document created in Utah Territory almost a decade later which implies that Wales was a Latter-day Saint (even though an even later source indicates he was not LDS. Both sources are discussed in detail below).[6] Whether or not he was baptized in Mississippi, the religious conversions of some members of the Crosby and Lay families dramatically altered the course of Hark Wales’ life.

Following their baptisms, the Crosby and Lay families decided to move westward, a determination which had far reaching implications for two of their enslaved men. The Crosby and Lay families sent their enslaved men, Hark and Oscar, under the oversight of John Brown to Council Bluffs, Iowa, where they would join a select group of pioneers that would set out to establish a new Zion.[7]

As it turned out Oscar and Hark became some of the first settlers to arrive in the Salt Lake Valley alongside LDS leadership and another black Mormon pioneer, Green Flake. In fact, by mid-July 1847, the three enslaved men became a part of LDS apostle Orson Pratt’s advance company consisting of 42 men and 23 wagons. The Pratt company was sent ahead of Brigham Young and the main group of migrants to improve the trail and chart a course into the Salt Lake Valley.[8] They mostly followed the path blazed the year before by the ill-fated Donner-Reed party and entered the valley on July 22, 1847. That night they camped at present-day 1700 South and 500 East and then moved North to between 300 and 400 South and Main and State Streets. They were plowing the land and planting crops by the time Brigham Young arrived on July 24.[9] Wales also set to work preparing land for William and Sytha Lay’s arrival. This likely included the construction of a cabin, as well as planting crops for them such as beans, wheat, turnips and potatoes. Black slavery thus arrived in the Salt Lake Valley with the original 1847 Latter-day Saint pioneers.

The year 1851 marked an important turning point in Wales’ life, and that year gives us more clues about his faith and relationship with the LDS Church. He would have been 26 years old when members of the Lay family decided to depart for San Bernardino, California on the Lyman-Rich wagon train. Before setting out across the present-day southern Nevada desert, the leaders of the group, apostles Amasa Lyman and Charles C. Rich, asked the men of the company to gather and pledge their loyalty to the expedition. The result was an April 1851 agreement compiled in Parowan, Utah, which included the names of 111 men. It was a list of those who were willing to be “subject to the Council of Elders Lyman and Rich in relation to their settlements and operations in California.”[10]

More than simply a list of names, the document also specified those in the company who did not belong to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. It further listed the names of five “colored” men who also pledged loyalty to the expedition, all of whom were enslaved at the time. Wales was one of the men who made the pledge but unlike some names on the list, his name did not include the notation “not a member” next to it. The document thus implies that Wales was a Latter-day Saint. It is the only known nineteenth-century record to indicate an LDS affiliation.[11]

In contrast to the April Agreement, pioneer Albert P. Rockwood’s overland trail journal described Hark as “not a member.”[12] However, Rockwood also indicated that the two other enslaved members of the company, Oscar Crosby and Green Flake, were not LDS when in fact both men were baptized, making Rockwood an unreliable source. Crosby and Flake were both rebaptized after their arrival in the Salt Lake Valley but no record survives to indicate that Wales joined them in that ritual. The April 1851 agreement is thus the only contemporary source to suggest his membership. If Wales was LDS as the April agreement implies, then his baptism probably took place in Mississippi in late 1843 or early 1844 when Oscar (Crosby) Smith was almost certainly first baptized along with white members of the Crosby and Lay families. Even still, a later source created after he returned from California to Utah indicates that Wales was not LDS and is perhaps the most reliable indication that he may have never been baptized.

Another reason why the journey to California in 1851 was important for Hark is because sometime after his arrival in California, he was freed. Most historians believe it was at this point that he changed his name from Hark Lay to Hark Wales so that it did not include the last name of his former enslaver. In modern-day Caribbean communities, the last name “Wales” is sometimes pronounced “Wallace” and it is possible Hark intended this pronunciation. Changing names after manumission was an important symbolic act for freed African Americans as was Wales’ decision to register to vote in the state of California in 1872 under his chosen name.[13]

As positive as it may have been for Wales to be free from the enslavement he was born into, 1851 was also likely a difficult year for him as the trip to San Bernardino separated him from his wife. In 1848 Wales had married an enslaved woman named Nancy who was owned by George Bankhead. Correspondence between Sytha Lay’s brother, William Crosby, and Brigham Young demonstrates that the Lays tried to keep Wales and his wife together but could not pay cash for Nancy before travelling to California and so the two were separated.[14] Hark and Nancy had one, possibly two, children together and Nancy was likely pregnant at the time Hark was taken to California. Their son Howard Egan Wales was a toddler that year, born in 1849, and their second son Henry was born in 1852 after Wales left. Henry took the last name of Nancy’s next husband, a Canadian man named James Valentine. Eventually they moved from Salt Lake City to Ogden, Utah and had several additional children.[15]

By 1852 a California census indicates that Wales had moved to Los Angeles and had not yet changed his name.[16] Almost twenty years later when he registered to vote, he lived in San Timoteo Canyon where he farmed the land under his new name.[17]

In the mid 1870’s Wales returned to Utah and invested in mining; he owned shares in Evergreen Consolidated Mining Company and bought ore in Big Cottonwood Canyon.[18] It is not clear that he ever reunited with his family. He is listed as living in Union, Utah as a farmer in an 1879 Salt Lake City directory.[19] In the 1880 census, he lived with Lucinda Flake Stevens (the daughter of Green Flake) and her family, a living arrangement that makes sense given the close relationship Wales likely had with Green Flake, his family, and the Black community at Union. The 1880 census for Utah also offers a unique clue regardig Wales' religious affiliation, or lack thereof, and is the strongest indication to date that he was not a baptized Latter-day Saint and likely never had been.[20]

The 1880 United States Census for Utah Territory included an informal religious accounting written in the margins of the census pages. There were no official religious categories on the census, but census takers in Utah that year agreed on various desiginations and wrote them along the left edge of each census page. A letter "g" next to a name meant "Gentile," a term used in Utah Territory to indicate people who were not members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, even if they were members of other faiths. An "m" next to a person's name (or no designation) meant "Mormon," while "a m" signaled "apostate Mormon" or someone who no longer practiced the faith. A "jm" indicated Josephite Mormon, or a person who belonged to the Reogranized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The census taker that year wrote "g" next to Wales' name, a clear indication that he was not understood to be a Latter-day Saint.[21]

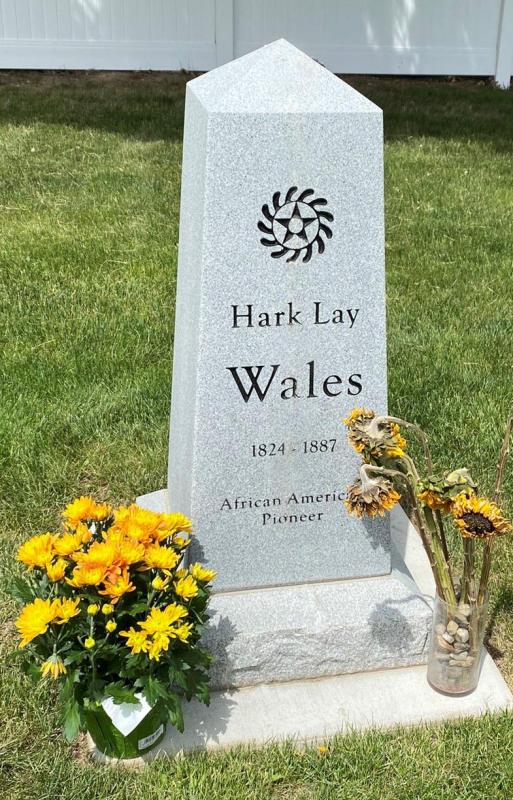

Although a death record has not been found, Wales likely died sometime in the 1880’s, and was buried in the Union Cemetery in an unmarked grave. In the twenty-first century Wales has been honored for his contributions as a Black Utah pioneer. In 2019, his grave at the Union Fort Pioneer Cemetery received a marker thanks to the work of historians, professional genealogists, and community groups such as the Utah Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society (AAHGS).[22] His name is also listed on the Brigham Young monument in downtown Salt Lake City, next to Oscar Crosby and Green Flake. Unfortunately, this monument describes the three Black pioneer men as “colored servants” despite opposition to this inaccurate terminology being vocalized for over 35 years.[23]

Because of the social dynamics of slavery, it will always be difficult to truly gauge the nature of Wales’ relationship with the Latter-day Saint settlers around him, both in California and in Utah. However, he did choose to return to Utah after gaining his freedom. His life choices to marry, own mining stock, and be buried in Union show he likely felt connected to the thriving African American community there in what is today Cottonwood Heights. There is no doubt that Wales’ life represents an important part of Utah, Latter-day Saint, and American history, especially his journey from Mississippi to Utah and then on to California. More importantly his life represents a journey from slavery to freedom, a microcosm of the more difficult reconciliation between the nation and its founding ideals.

By Megan Weiss

Primary Sources

Brown, John. Reminiscences and Journals, 1843–1896, Volume 1, 1843 May–1860 April. MS 1636. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

California State. 1852 Census. Los Angeles.

Crosby, William to Brigham Young. 12 March 1851. Brigham Young Office Files. CR 1234 1, Reel 31, Box 22, Folder 6. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Egan, Howard. Journal, July 13, 1847. Pioneer Database, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

“Genealogy.” Salt Lake Herald Republican, 30 May 1915, 8.

Great Registers, 1866–1898. Sacramento: California State Library, 2011. Document also on FamilySearch

John Crosby Probate. Monroe County, Mississippi, 1842. Mississippi. U.S. Wills and Probate Records, 1780–1982. John Crosby. Mixed Estate Records. Case 139.

List of 1847 Pioneers. Nauvoo City Court Docket Book. MS 3441, Item 163. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

“List of those willing to be counceled by A. Lyman, C.C. Rich.” MS 889. Charles C. Rich collection. California papers, 1851–1856. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

“Mining Notices.” Salt Lake Tribune. 18 November 1875, 3; 2 December 1875, 3.

“Mormon Plaque Names 3 Blacks.” Idaho Free Press. 2 April 1975, 13.

Philips, Albert F. “Know Utah.” Salt Lake Telegram. 14 October 1929.

Rockwood, Albert P. Pioneer Journal, April-July 1847. MS 1449. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

United States. 1880 Census. Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Union.

Utah Territorial Census, 1851. “Schedule 2.” MS 2672. Church History Library. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Salt Lake City, Utah.

Secondary Sources

Brown, John. Autobiography of Pioneer John Brown, 1820–1896. Edited by John Zimmerman Brown. Salt Lake City: Stevens & Wallis, 1941.

Carter, Kate. The Story of the Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1965).

Coleman, Ronald G. A History of Blacks in Utah, 1825–1910. PhD Dissertation. University of Utah, 1980.

Dixon, W. Randall. “From Emigration Canyon to City Creek: Pioneer Trail and Campsites in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847.” Utah Historical Quarterly 65, no. 2 (Spring 1997): 155–64.

Gates, Henry Louis Jr. and Meaghan E. H. Siekman. “Tracing Your Roots: Were Slaves’ Surnames Like Brands?” The Root, June 16, 2017.

“Henry Tells it like it Is.” Salt Lake Community College Student Newspapers. 21 February 1989.

Hunter, J. Michael. “The Monument to Brigham Young and the Pioneers: One Hundred Years of Controversy.” Utah Historical Quarterly 68 no. 4 (2000).

Prescott, Cynthia Culver. Pioneer Mother Monuments: Constructing Cultural Memory Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019.

Stack, Peggy Fletcher. “New grave marker to honor African American slave who helped Mormon pioneers build their Utah Zion.” Salt Lake Tribune. May 26, 2019.

Thiriot, Amy Tanner. “Guest Post: Hark (Lay) Wales: A Slave in Zion.” Keepapitchinin, July 24, 2012.

Thiriot, Amy Tanner. Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847–1862. Salt Lake City, University of Utah Press, 2022.

[1] Special thanks to Amy Tanner Thiriot and Sheri Orton for their work in piecing together Wales’ history. For more reading on Wales, look for Thiriot’s forthcoming book Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847–1862.

[2] John Crosby, Probate, Monroe County, Mississippi, 1842, Mississippi, U.S. Wills and Probate Records, 1780–1982, John Crosby, Mixed Estate Records, Case 139, image 267–68. The estimated birth year is derived from United States, 1850 Census, Slave Schedules, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, entry for William Lay, which was actually created in 1851 and gives Hark’s age at the time as 26.

[3] John Brown, Reminiscences and Journal, vol. 1, 1843 May–1860 April, MS 1636, 22–23, 28, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah; John Brown, Autobiography of Pioneer John Brown, 1820–1896, ed. John Zimmerman Brown (Salt Lake City: Stevens & Wallis, 1941), see page 49 for a brief description of the Crosby family according to family tradition.

[4] John Brown, Reminiscences and Journal, vol. 1, 28.

[5] Charmaine Lay Kohler, Southern Grace: A Story of the Mississippi Saints (Boise, Idaho: Beagle Creek Press, 1995), 60.

[6] “List of those willing to be counceled by A. Lyman, C.C. Rich,” MS 889, Charles C. Rich collection, California papers, 1851–1856, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. Century of Black Mormons is indebted to Kristine Shorey Forbes for bringing this document to our attention.

[7] John Brown, Reminiscences and Journals, vol. 1, 54–55; Brown, Autobiography of Pioneer John Brown, 17–18, 71–72.

[8] List of 1847 Pioneers, Nauvoo City Court Docket Book, MS 3441, Item 163, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah; Howard Egan, journal, July 13, 1847, as in Pioneer Database.

[9] W. Randall Dixon, “From Emigration Canyon to City Creek: Pioneer Trail and Campsites in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847,” Utah Historical Quarterly 65, no. 2 (Spring 1997): 155–64.

[10] “List of those willing to be counceled by A. Lyman, C.C. Rich.”

[11] “List of those willing to be counceled by A. Lyman, C.C. Rich.”

[12] Albert P. Rockwood, Pioneer Journal April-July 1847 1847-1853, MS 1449, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[13] For more on the importance of surnames for freed slaves see Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Meaghan E. H. Siekman, “Tracing Your Roots: Were Slaves’ Surnames Like Brands?” The Root, June 16, 2017. For Wales’ voter registration see, Great Registers, 1866–1898 (Sacramento: California State Library and Ancestry.com, 2011). Document also on FamilySearch

[14] William Crosby to Brigham Young, 12 March 1851, Brigham Young Office Files, CR1234 1, Reel 31, Box 22, Folder 6, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[15] United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, 13th Ward; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, 13th Ward; “An Aged Warrior Gone,” Ogden Standard, July 4, 1893, 1; “Mrs. Nancy Vallantyne,” Ogden Standard, April 24, 1894, 4.

[16] California, 1852 Census, Los Angeles.

[17] Great Registers, 1866–1898.

[18] “Mining Notices,” Salt Lake Tribune, 18 November 1875, 3.

[19] Amy Tanner Thiriot, “Guest Post: Hark (Lay) Wales: A Slave in Zion,” Keepapitchinin.org, July 24, 2012.

[20] United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Union.

[21] Samuel A. Smith, "The Wasp in the Beehive: Non-Mormon Presence in 1880s Utah," MS thesis, (Pennsylvania State University, 2008), 27-36; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Union.

[22] Peggy Fletcher Stack, “New grave marker to honor African American slave who helped Mormon pioneers build their Utah Zion,” Salt Lake Tribune, May 26, 2019.

[23] “Henry Tells it like it Is,” Salt Lake Community College Student Newspapers 21 February 1989. For more on this see Cynthia Culver Prescott, Pioneer Mother Monuments: Constructing Cultural Memory (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 2019): 142 and J. Michael Hunter, “The Monument to Brigham Young and the Pioneers: One Hundred Years of Controversy,” Utah Historical Quarterly 68 no. 4 (2000).

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.