Walker, Lydia

Biography

Lydia Walker and two other women, Cynthia Ely and Penny Utley, are the first known Black women baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Wilford Woodruff, then a missionary for the Church created a membership book dated July 4, 1835 in which he wrote Lydia Walker’s name. It is the only known source wherein anyone acknowledged Lydia’s life by name. Were it not for Woodruff's list, Lydia Walker may have been lost to history. Woodruff also documented her race. After listing the other members of the Eagle Creek Branch in Benton County, Tennessee, Woodruff wrote “Names of Coloured Members” and then added “Lydia Walker.” She was the only person in that branch so designated.[1]

Like most Black people in the antebellum South, Lydia was enslaved. Slaves generally were known by the last name of their enslaver, a likely scenario for Lydia. Woodruff also listed a Henry and Catherine Walker as white members of the Eagle Creek Branch and he sometimes referred to a John Walker in his journal.[2] However, surviving sources, including tax and census records from Benton and Obion counties (where Henry and Catherine Walker lived in 1850) do not show that any of these Walkers owned slaves. Only one man in the county surnamed Walker is a possibility. A man named James Walker consistently owned a single slave in tax records dating 1836, 1837, 1838, 1839, and 1842. Tax records, however, do not record children too young to work and therefore did not include all of Walker’s enslaved people. Though he did not claim to own a slave in the 1840 census (an unlikely scenario given the evidence in the tax records), the 1850 Slave Schedule does list Walker with one enslaved woman, age 34, and six children who were 1, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 14 years old. Other people surnamed Walker who lived in the area either did not own slaves or owned only one male slave old enough to have been baptized by 1835. In all likelihood, James Walker and his wife, Indiana, enslaved Lydia. They were relatives of Henry and Catherine Walker and may have attended Latter-day Saint meetings with them.[3]

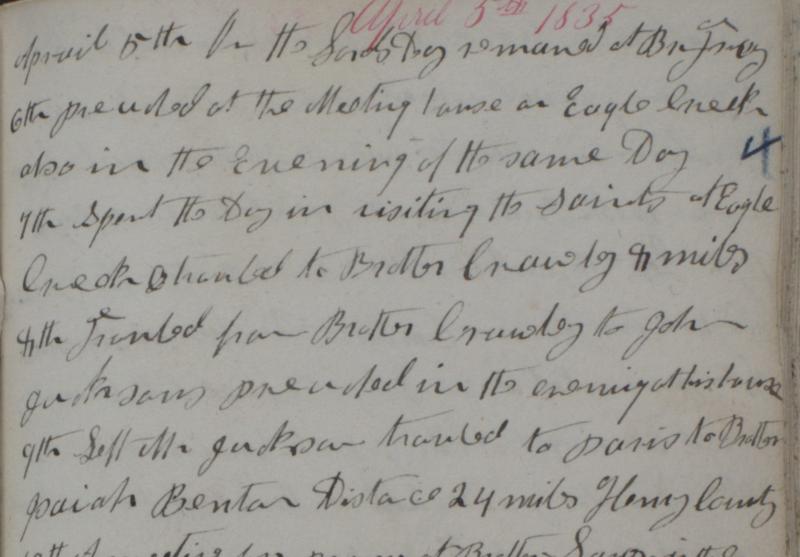

Under this premise, Lydia was nineteen years old when Woodruff named her a member of the Eagle Creek Branch. It was a small congregation in rural northwestern Tennessee with twenty members at the time Woodruff created his record. Warren Parrish, another missionary, preceded Woodruff to the area in late 1834 and likely organized the branch then or in early 1835. Woodruff first “preached at the Meeting house on Eagle Creek” on April 6, 1835, and spent the following day “visiting the Saints at Eagle Creek.”[4] Woodruff or Warren Parrish likely baptized Lydia Walker, although Woodruff failed to specify the names of those he and Parrish baptized in the region. In any case, Lydia was the only Black person in the branch.[5]

When Parrish left the region in June 1835, he ordained 91-year-old Caswell Matlock a deacon to presided over the small congregation. Parrish ordained Woodruff an elder at the same meeting. If Lydia was present that day she would have witnessed a future president of her church receive the faith’s higher priesthood order, known as the Melchizedek priesthood, at Eagle Creek. On that occasion Woodruff wrote, “On the LORDS DAY Brother WARREN PARRISH Preached his farewell sermon to the E[a]gle Creek branch. . . . And . . . Ordained me an Elder. . . . We truly had an affecting time. Partook of the Sacrament[.] closed the meeting by singing A farewell song.”[6]

Matlock then presided over the branch as deacon until he passed away six months later. It is not clear who assumed leadership of Eagle Creek in the wake of Matlock’s death, but it continued to function as a branch with fifteen to seventeen members “in good standing” up through at least 1844. After Joseph Smith’s murder that year and the subsequent move of the main body of Saints to the West, news of the Eagle Creek Branch disappeared from church records.[7]

Presumably Lydia Walker was one of the members in good standing up through 1844, although it is impossible to know. Her enslavers, James and Indiana Walker did not convert, though they may have gone to meetings with or heard about Latter-day Saint teachings from their relatives, Henry and Catherine Walker. No matter how Lydia learned of the Gospel of Jesus Christ as taught by the Latter-day Saints, it seems evident that she was granted the agency to get baptized and likely to travel to meetings. That she converted independent of her enslavers demonstrates how important the connection to the Church must have been to her.

Lydia spent the next 15 years or more toiling for the Walker household. Exploited for her reproductive ability, she spent much of her life pregnant and nursing. She was either pregnant or soon would be when she joined the Church and may have already given birth to a child who had been sold away from her by 1850. In fact, the 1850 slave schedule suggests that the Walkers followed a pattern in which they kept enslaved boys to work on their farm and sold the girls once they were old enough.[8] Lydia may also have been a wet-nurse to Indiana’s children, required to prioritize them over her own children. Moreover, she would have taken on the work that was close to the house, such as gardening, doing the laundry, drawing water from a well, chopping wood, cooking and watching the children. Her children probably played with their enslaver’s children until they were old enough to be sold or sent to work in the fields.[9]

There is no record indicating who was the father (or fathers) of Lydia’s children. In order to exploit reproduction, many enslavers allowed and even encouraged the people they enslaved to informally marry and have conjugal relationships with other slaves, even those from other plantations and farms. It is also possible that James Walker could have been a father to some or all of Lydia’s children, as it was common for enslavers to sexually exploit enslaved women.[10]

Indiana Walker died in 1857 and James Walker in 1858. Their oldest son, Dewitt C. Walker took over the estate, which was in debt at the time. An 1858 estate inventory listed three slaves: George age 21, Jane age 17, and Wayne age 12. In the 1860 slave schedule, Dewitt enslaved three individuals: A man and a woman, both 23 years old and a boy who was 14. These records thus suggest that at least by the time of James Walker’s death, Lydia was no longer enslaved to him. She had either been sold, died, or freed by that point although freedom was unlikely given that in 1831 Tennessee made manumission illegal unless the person manumitted promised to leave the state.[11]

There are tantalizing references in Freedmen’s Bureau and census records to women with similar names to Lydia after the Civil War. A Liddy and Lydia Walker show up in a hospital record in South Carolina three times, for example. A Lyda Walker obtained clothes and children’s shoes at a distribution point in Gordonsville, Virginia in 1868. These and other close matches can nonetheless be ruled out through biographical and circumstantial evidence. If still living, Lydia Walker may have changed her last name after the war, making it all but impossible to trace her through available records.

No matter her fate, Lydia was a woman who, when given the chance, chose to follow her faith in God and embrace an upstart religion. Were it not for Woodruff’s membership list she may have been lost to history. As it stands, she became a Latter-day Saint pioneer in Tennessee and was one of the first three Black women known to have joined the Church.

By Ami Chopine

[1] Wilford Woodruff, Membership Record Book, 1835, Wilford Woodruff Collection, MS 5506, box 2, folder 6, Church History Library. Listed in the Eagle Creek, Tennessee Branch in 1835. “Eagle Creek Branch,” Mormon Places; Bruce Crow, “Eagle Creek Branch,” Amateur Mormon Historian, June 4, 2012.

[2] The Wilford Woodruff Journals, Typescript, 6 vols., edited by Dan Vogel (Salt Lake City, Utah: Benchmark Books, 2020), May 7, 1835, 1:39; June 30, 1835, 1: 44.

[3] Tennessee, U.S., Early Tax List Records, 1783-1895, Benton County, 1836, 1837, 1838, 1839, 1842, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, Tennessee.

United States, 1840 Census, Tennessee, Benton County, Entries for Henry, James, and William Walker.

United States, 1850 Census, Tennessee, Benton County, entries for Henry and James Walker.

[4] Wilford Woodruff Journals, April 6 and 7, 1835, 1:36.

[5] Wilford Woodruff, Membership Record Book, 1835.

[6] Wilford Woodruff Journals, June 28, 1835, 1:42-43.

[7] Bruce Crow, “Eagle Creek Branch,” Amateur Mormon Historian, June 4, 2012; “Eagle Creek,” Times and Seasons (Nauvoo, Illinois), August 1, 1844, 605-606.

[8] United States, 1850 Census, Slave Schedule, Tennessee, Benton County, James Walker.

[9] Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999).

[10] Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W. W. Norton, 1999).

[11] "Tennessee Probate Court Books, 1795-1927," Settlements, 1860-1869, Vol. A, pages 4 and 10, images 27 and 30; "Tennessee Probate Court Books, 1795-1927," Settlements, Wills, 1855-1916, Vol. 1, pages 247, 262, and 264; United States, 1860 Census, Slave Schedule, Tennessee, Benton County, D.C. Walker; J. Merton England, "The Free Negro in Ante-Bellum Tennessee," The Journal of Southern History Vol. 9, No. 1 (Feb., 1943): 37-58.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.