Willson, Mary

Biography

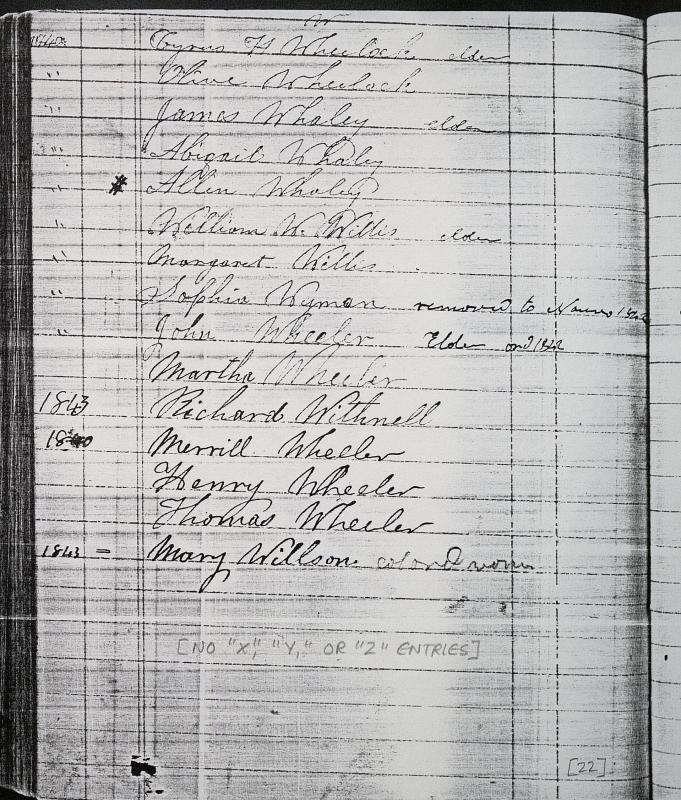

We know very little about Mary Willson. The only surviving source to name her and describe her as a “colored woman” is a list of rebaptisms performed in Nashville, Lee County, Iowa. Nashville was a small settlement south of Nauvoo, across the Mississippi River. In the early 1840s, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints bought land in Nashville on credit for members seeking to escape persecution in Missouri. Over time, as the Saints gathered, the Nashville Branch expanded to include approximately ninety members.[1]

Mary Willson was a part of this branch. She, along with about ten other people, was rebaptized in 1843.[2] At the time, rebaptisms in the LDS Church were not uncommon and were performed for various reasons. Many members chose to be baptized again after repenting of serious transgressions, or to prepare for sacred temple rituals, or as an outward symbol of their recommitment to Jesus Christ and the Latter-day Saint cause. Reentry into the Church after excommunication also required rebaptism. Additionally, some members were rebaptized after long journeys, serving as a symbol of their joining the Church in their new home.[3] In the case of the Nashville branch, the record of rebaptisms indicates that those receiving the ritual “had been baptised [sic] before but added to this branch by being rebaptised [sic].”[4]

Frustratingly, the branch rebaptism records do not include any identifying information such as a birthdate, birthplace, original baptismal date and location, or parents’ names—only the year and name of the person rebaptized. In Mary’s case, she was likely first baptized near her home somewhere in the Eastern or Southern United States. She likely would have learned about the Church from missionaries sent to share the gospel and increase the Church membership. She was probably baptized by a missionary who had traveled to her home community.

Sometime later, she would have been part of the gathering movement of the Church. Evidence suggests that she left her home behind to join the larger body of Saints in Illinois and Iowa. Traveling long distances, often difficult and dangerous for anyone, would have been more so for Mary. She was a “colored woman,” though it is unknown if she was free or enslaved.[5] If she were a free woman of color, she would have faced the risk of being captured and sold into slavery. She may have had to pay unreasonable fares and fines that her white counterparts were not subjected to. It is possible that she had to walk a given distance because boats and carriages may have refused to serve her because of her race. Black converts Jane and Isaac Manning and their families faced just such a rejection when they were denied passage on a boat as they migrated from Connecticut to Nauvoo.[6]

Alternatively, Mary could have been enslaved to a white family. If this is the case, she may not have had a choiceto leave her home. She may have been forcefully separated from her community and taken to Iowa with those who enslaved her.[7] Even still, surviving evidence, slim as it is, suggests that Mary was free. Nashville branch records include Willson as a last name for Mary but do not include any other people by the last name of Willson, an indication that she was not associated with enslavers with the same last name or assumed to carry the last name of her enslaver. The clerk who created the record of Mary’s rebaptism also described her as a “colored woman” but did not include the words “servant of” or “belonging to” anyone else in the branch, notations that are more typical for baptisms of enslaved people. “Colored woman” with no relational identifiers at least suggests that she was free.[8]

After a potentially long journey, Mary ended up in the small branch of Nashville. She probably chose rebaptism as a symbol of her rebirth into this new community surrounded by members of her faith.

Without any additional biographical information, it is impossible to trace Mary beyond the Nashville, Iowa branch. Though there are a variety of women named Mary Wilson associated with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, none can be definitively matched with the Mary Willson rebaptized in Iowa in 1843. Census records give no evidence that Mary lived in the area before her rebaptism and, as the majority of Latter-day Saints left Iowa before the 1850 census, it is impossible to track Mary’s residences thereafter. Searches for other records, such as death, marriage, or migration, do not yield conclusive matches. Thus, our knowledge of Mary Willson is limited to the sparce Nashville, Iowa, branch record.

By Abby Hilbig

[1] Maurine Carr Ward, “The Mormon Settlement at Nashville, Lee, Iowa: One of the Satellite Settlements of Nauvoo,” Nauvoo Journal 8 (Fall 1996): 10–24.

[2] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Nashville Branch Membership Roster, 1839-1843, LR 5167 21, image 59, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] D. Michael Quinn, “The Practice of Rebaptism at Nauvoo,” BYU Studies Quarterly 18, no. 2 (1978): Article 9.

[4] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Nashville Branch Membership Roster, 1839-1843, LR 5167 21, image 21, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[5] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Nashville Branch Membership Roster, 1839-1843, LR 5167 21, image 59, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[6] Quincy D. Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel: The Life of Jane Manning James, a Nineteenth-Century Black Mormon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2019).

[7] Newell G. Bringhurst, “African American Converts and the Mormon Church,” in Black and Mormon, ed. Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 25–42.

[8] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, Nashville Branch Membership Roster, 1839-1843, LR 5167 21, image 59, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. For examples of relational identifiers in baptismal records of enslaved people see Jeffrey D. Mahas, “Hagar,” Century of Black Mormons; Jenny Hale Pulsipher, “Nancy Smith,” Century of Black Mormons; Benjamin Kiser, “Green Flake,” Century of Black Mormons; and Ami Chopine, “Jack,” Century of Black Mormons.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.