Early exploration and exploitation

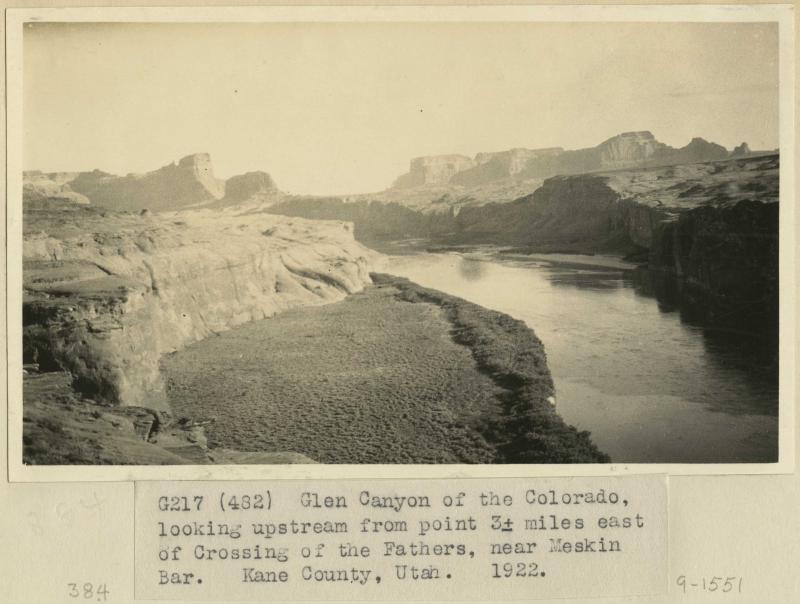

Glen Canyon occupies a winding 163-mile stretch of the Colorado River and includes several side canyons. The entrenched Colorado presented a barrier to passage through its surrounding region, and even at the height of the Ancestral Puebloan culture a thousand years ago, few people lived there permanently. When the first Spanish exploring party, the Dominguez-Escalante expedition, passed through the region in 1776, the Colorado blocked their return route to Santa Fe, and it was in Glen Canyon that they found a relatively easy ford at what became known as “The Crossing of the Fathers.”

The country remained unknown and unmapped until Major John Wesley Powell led a series of river expeditions down the Green and Colorado Rivers from 1869 to 1872. After a grueling descent of Cataract Canyon in 1869, the party appreciated the long stretch of calm water that slowly passed through Glen Canyon.

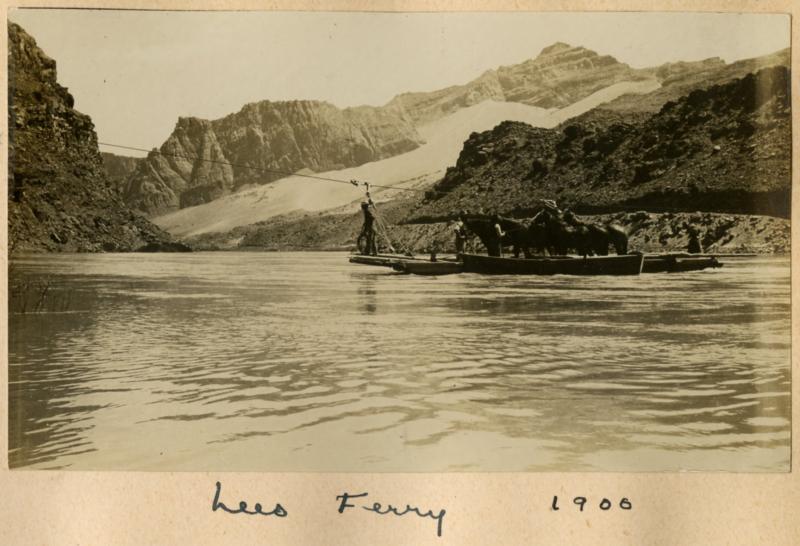

At the same time, Mormon settlement was expanding from southwestern Utah into Arizona. The need for a direct route through the Colorado Plateau led to John D. Lee’s operation of a ferry at the foot of Glen Canyon. In 1880, a band of pioneers bound for the San Juan River found their progress blocked by the canyon, and had to blaze a trail down the rift in the canyon wall known as “Hole-in-the Rock,” before continuing on.

With the rest of the West now the site of much prospecting for gold and other minerals, Glen Canyon caught the interest of fortune-seekers. With the assumption that the banks of the Colorado held gold washed down from the Rocky Mountains, Robert B. Stanton developed a plan to dredge the sand in Glen Canyon to recover the gold dust. The gold was there, but in too limited quantities to be profitable, and the dredge was abandoned.

Exploration would continue, including by government surveyors such as the geologist Herbert Gregory. His several expeditions through the southwest from 1909 into the 1940s often brought him to Glen Canyon.