The coming of Glen Canyon Dam

As early as the 1920s, when the governments of seven Western states came to an agreement on how to apportion the water of the Colorado River basin, Glen Canyon was marked as a possible site for a large reservoir. The Colorado River Compact of 1922 mandated a dam that would regulate the flow of river water between the upper and lower basins. The 1928 decision to build Boulder (later Hoover) Dam forestalled plans for a dam near Lees Ferry, but it remained an idea and was actively promoted by interests in Arizona.

When, in 1949, the Bureau of Reclamation proposed a series of dams in the Colorado River basin, the plans for Echo Park in Dinosaur National Monument brought out conservationists in force to oppose it. A consequence of this battle was the agreement by the environmentalists to support the Glen Canyon proposal if the Dinosaur site were dropped. Glen Canyon was still little-known, but after the project was authorized in 1956, the environmental community became increasingly familiar with Glen Canyon and realized what they had agreed to surrender.

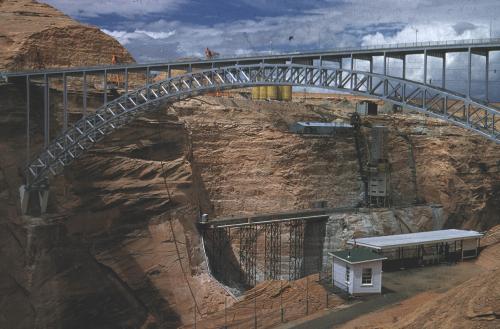

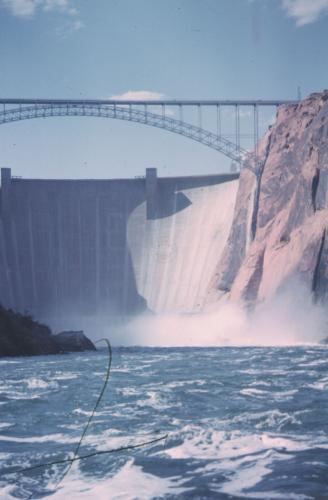

Construction on the Glen Canyon Dam took place between 1956 and 1963, and a new highway bridge spanned the Colorado during the same period. River traffic increased during the construction period, as people wanted to see what was about to be covered by a giant reservoir. Archaeological surveying also took place in order to document the soon-to-be flooded lowlands and salvage historical relics. Even after the gates were closed in 1963, river runners documented the rising waters of Lake Powell as it flooded special places such as the “Music Temple” and the “Cathedral in the Desert.”

Today a different tourist industry has become well-established at Lake Powell. When the lake was full, boaters could sail up to the foot of Rainbow Bridge. In 1965, Wallace Stegner wrote: “Though these walls are lower and tamer than they used to be… Lake Powell is beautiful. It isn’t Glen Canyon, but it is something in itself. The contact of deep blue water and uncompromising stone is bizarre and somehow exciting.” Even so, “in gaining the lovely and the usable, we have given up the incomparable.” (Wallace Stegner, from a Holiday Magazine article quoted in Russell Martin, A Story that Stands Like a Dam: Glen Canyon & the struggle for the soul of the West (University of Utah Press, 2017)

The loss of Glen Canyon inspired the environmental community to successfully challenge other dam projects proposed for the Grand Canyon downstream. And some parties never gave up on Glen Canyon, hoping in recent years to see the dam “de-commissioned” and breached. Meanwhile, increasing drought in the West has lowered the level of Lake Powell considerably, sometimes even exposing old landscapes such as the Cathedral in the Desert. The saga continues…