Early Celebrations

On May 10th, 1919, wreaths of yellow sunflowers were made to adorn the pyramid-shaped monument that marked the spot where “the wedding of the rails” occured on May 10th, 1869. Despite the floral arrangements, no one arrived at Promontory Summit for that 50th Golden Spike Anniversary, according to Bernice Houghton Gerristen, who was just a child at that time, living in the area. Celebrations that year were contained to Ogden, Utah. Gerristen's story, along with many others about the Transcontinental Railroad and Golden Spike historical site can be found in the Golden Spike Oral History Collection, which were recorded in 1974. By the time of the Golden Spike Centennial in 1969, it would be difficult to imagine such a lack of attendance and ceremonies at Promontory Summit to commemorate the famous matrimony of railways.

It was in the early 1930s, according to Bernice Gibbs Anderson, who was interviewed in 1974 for the Golden Spike Oral History collection, when the Sons and Daughters of the Pioneers led an effort to commemorate the Golden Spike anniversaries on May 10th at Promontory Summit. A script of dialogue for reenactors to speak while recreating the event was written by Marie Thorne Jepson of Daughters of the Pioneers from Brigham City. Ms. Bernice Gibbs Anderson, Honorary Chairman of the Golden Spike Committee, worked tirelessly to establish the Golden Spike National Monument. From reviewing a collection of her letters to public officials, including the President of the United States, various Utah representatives, the Salt Lake City Chamber of Commerce, National Park Service Director, and the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Gibbs Anderson pleads the importance of the site to be preserved by national monument status. In a letter to U.S. President Harry S. Truman in 1949, Gibbs Anderson states "since I have worked for the past twenty years trying to publicize this spot, I shall work for the next twenty, if necessary, until something is done about it." In a letter from the National Park Service that same year, NPS Assistant Director Tolson deemed Promontory Summit better suited for the state of Utah to preserve, but Gibbs Anderson persisted her national monument campaign for many years with successful results.

From Bernice Gibbs Anderson's 1974 oral history, her lifelong interest in the site where the wedding of the rails took place is discussed at length. Since she was a child, starting in 1905, Gibbs Anderson was captivated by cowboy stories about the Chinese and Irish railway laborers, often in deadly clashes with each other, and the completion of the first Transcontinental Railroad with a golden spike. By 1974 the National Park Service had changed their stance about protecting the Golden Spike site, and Gibbs Anderson applauded their efforts, except for the destruction of a large windmill that used to be on the grounds that she claims was built with pegs instead of nails. "They bulldozed it down and I can't understand why." From the Utah Department of Heritage and Arts, a photograph [see left] of Bernice Gibbs Anderson in front of this windmill, taken in 1936, can be seen. A collection of photographs of Promontory Summit, including Golden Spike anniversary events, taken or donated by Bernice Gibbs Anderson , can be viewed in the Utah Department of Heritage and Arts collections.

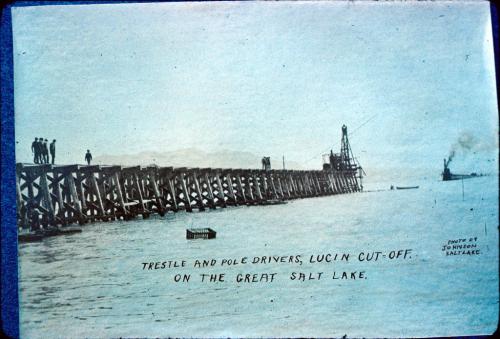

After the turn of the 20th century, the section of transcontinental railway line through Promontory, Utah was barely in use. With the creation of the Lucin Cutoff, a stretch of 102 miles of railway from Ogden to Lucin, Utah, which shortened the route by 44 miles with reduced curves and grades. Built by the Southern Pacific Railway Company (successor to the Central Pacific Railway Company) between 1902-1904, the cutoff included 12 miles of wooden trestles across the Great Salt Lake. By the time WWII began, in 1942, this track was targeted for metal donation to the war effort.

Work began in the summer of 1942 to remove the old Promontory line, consisting of 123 miles of track. Removing the track was an arduous task for the crews with summer heat, brush fires, and rattlesnakes plaguing the effort. By September, nearly all of the track had been removed, leaving enough for two engines and the "undriving" of the last spike. Opposite of the standard anniversary reenactments, instead of hammering the final spike, the last spike was removed in September, 1942. Over 200 people gathered for this event and it is well documented in the Utah Historical Society's Department of Heritage and Arts Classified Photographs and the Salt Lake Tribune Negatives digital collections. While many saw the dismantling of the old line a necessary to support the war, others saw it as a disrespectfully destroyed by the "vandal of practicality" according to the Utah Historical Society's 1995 History Blazer.

Anniversary celebrations continued through the decades leading up to the centennial in 1969. Although the land was designated a National Historic Site in 1957, it was not federally acquired until 1965. According to the Golden Spike Oral Histories, the govenment had little involvment in the celebrations until the later 1960s. The Box Elder County Community led the effort in commemorating the anniversary Golden Spike events at Promontory Summit. Although, anniversary events occured in other areas of Utah, in the late 1940s C.R. Rockwell remembered there being a desire to keep the Golden Spike events in Box Elder County - the message to Ogden was "lay off the Golden Spike, it belongs in Box Elder County." From looking at the photographs of Golden Spike anniversaries available in the Utah Historical Society's Department of Heritage and Art's digital collections, there are some commonalites that remain true today. Reenactmentors, representing Leland Stanford, President of the Central Pacific and Grenville Dodge, representing the Union Pacific's failed swings to nail the final golden spike, along with a telegrapher to communicate the event to the country in real-time. Crowds of people and the automobiles that carried them to this remote place are also present. From inspecting the photographs further, additional ceremonies, beyond the historical reenactments, are evident. Native Americans dancing amongst a crowd of spectators can be seen in the 1964 Golden Spike anniversary, while a choir group with instruments can be seen in 1965.