Transcontinental Railroad

The connection of the Central Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads which created the First Transcontinental Railroad just north of the Great Salt Lake, was the culmination of six and a half years of hard labor by tens of thousands of men. The implications of this continuous stretch of railway was monumental: advancing transportation of goods and people by extremely expedited travel time to the West Coast, coast-to-coast telecommunication, along with the expansion and dramatic change to the American West. Before reviewing the Golden Spike celebrations over time, it is important to understand why this occasion has been commemorated for 150 years with ceremonies attended by up to thousands of people and the land where this took place has been federally protected by the National Park Service. This section will provide a brief overview of some basic facts of the creation of the First Transcontinental Railroad.

The First Transcontinental Railroad was a 1,912 mile continuous stretch of track, connecting the San Francisco wharf to Omaha, Nebraska. This railway was completed by two companies, the Central Pacific Railroad (CPRR) and the Union Pacific Railroad (UPRR). The CPRR began in Sacramento, California on June 28, 1861, but work didn’t begin until January 8, 1863 due to waiting on Congress to pass laws to subsidize part of the construction costs. The Pacific Railway Act, signed by President Abraham Lincoln on July 1, 1862, both enacted the UPRR and ensured that the CPRR would would receive the same subsidy of government bonds and land grants as the UPRR. While the CPRR began work in early 1863, the Union Pacific didn’t start laying track until 1865.

The CPRR's 690 miles started in Sacramento, California and worked east, facing the most difficult terrain through the rugged Sierra Nevada mountain range. From Sacremento to Donner Summit, an elevation of 7,000 feet was reached in just 90 miles. The UPRR's 1,087 miles started in Omaha, Nebraska and worked west through relatively smooth plains. The landscape wasn't as imposing as the CPRR route, but Native American tribes hostile to the invading iron horses and the men who came with them posed a different threat by attacking and killing grading scouts. Completing this railway called for significant fleets of manpower. Given the lack of accessiblility to the West Coast at that time, the labor supply in California was not plentiful, adding to this, most men in that area prefered mining work. As a result, the CPRR looked to using Chinese emigrants who came to California to flee the Taiping Rebellion in China. The Chinese manual laborers proved to be quick learners and hard working. While CPRR did employ some Irish emigrants and Americans as well, the majority of the CPRR workforce on the Transcontinental Railroad was Chinese. Chinese railway workers were instrumental in drilling tunnels, blasting rock, and laying track through solid granite Sierra Nevada mountains. Their work was often the most dangerous, and while the death toll is unknown, more than 1,000 Chinese are estimated to have died while building the railroad. With the end of the Civil War coinciding with labor recruitment for the Union Pacific line, many veterans from both the North and South, including emancipated African Americans, came to work on the railroad beginning in Nebraska. Once the railroad neared Utah, Mormon laborers joined the ranks to complete the Transcontinental Railroad.

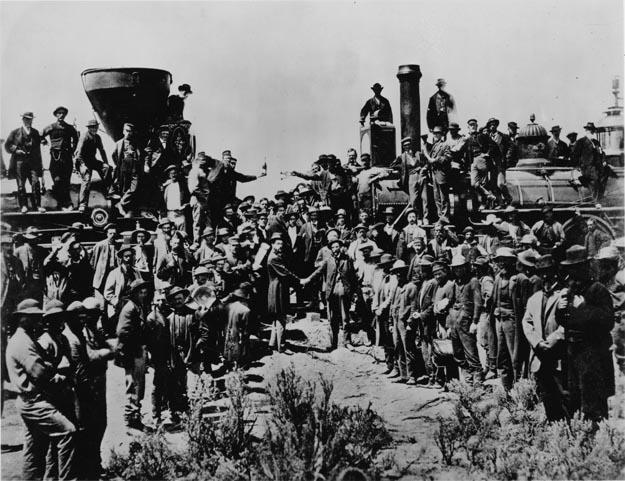

Each side of railway line, the Union Pacific and Central Pacific, photo-documented the progress made as they moved toward their meeting at Promontory Summit, Utah. The Union Pacific hired Andrew J. Russell, former infrastructure photographer in the Union Army during the Civil War, who joined the effort in 1868 after the Union Pacific had completed most of the railway work in Nebraska. The most comprehensive collection of Russell’s plates can be viewed online at the Oakland Museum of California Digital Collections. Alfred A. Hart (1816-1908) was the resident photographer of the Central Pacific's progress, who was present for the duration of the line's completion. The most complete collection of A. A. Hart's documentation of the Central Pacific's work can be found in the Stanford University Digital Repository and Huntington Library Digital Collections.

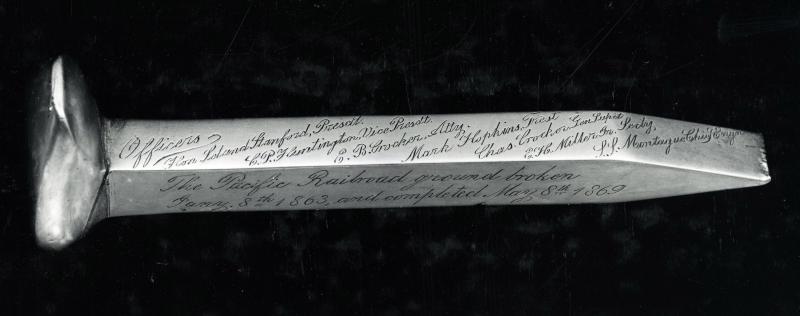

When the Central Pacific and Union Pacific railroads finally met at Promontory Summit in May of 1869 and the events that took place to finalize the unification of the two sides has been recreated to commemorate the Golden Spike ever since. Dignitaries from both railway companies traveled to Promontory Summit for the occasion. The driving of the final, golden spike was originally to occur on May 8th, 1869, but Union Pacific employees due back wages prevented UP Vice President Thomas Durant's train from continuing past Piedmont, Wyoming until payments were delivered. With this slight delay, the UP officials including Durant and Chief Engineer, General Grenville Dodge arrived on May 10th, while Leland Stanford, President of the Central Pacific Railroad waited two days for their arrival. There were four commemorative spikes to be symbolically tapped into a laurelwood ties. Presented that day were two golden spikes, a silver spike, and a spike made of both gold and silver. One of the golden spikes, considered the official golden spike, was a gift to Leland Stanford of CP. It was engraved on all four sides, including the names of the railroad officers and directors along with start and end dates of construction. After a rousing speech from Leland Stanford, Thomas Durant was absent from speaking at the event due to a headache, the railroad officials were all given a swing at nailing the final spike but missed. Fittingly, it was a railway worker who drove in the final spike, and with that the Western Union telegrapher present tapped D-O-N-E to the nation at 12:47 p.m. Monday, May 10th, 1869.