Utah Air Quality History, 1850s–1920s

During the initial decades after the arrival of the Latter-day Saints settlers into the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, the primary fuel used for heating homes was wood. According to J. Leo Fairbanks, a Salt Lake City commissioner in the 1920s, tradition had it that the smoke from the wood fires would leave a layer of blue smoke in the air for days at a time. Still, it doesn’t appear from available documents that potential pollution caused by the smoke was a major issue in this period. Church President Brigham Young, in a speech in 1860, remarked that “good, pure air” “constitutes health, wealth, joy, and peace”—but he was referring primarily to indoor air and the necessity of good ventilation in homes. It was not until the 1880s and ‘90s, when the use of coal became widespread in Salt Lake City, that the air pollution caused by fuel combustion became a major concern.

In the 1880s, editorials in the Deseret News began to note the seriousness of what was called “the smoke nuisance” and urge private industry to address the issue before regulations became necessary, though they did not have the technology available to do so. Salt Lake City’s first air quality ordinance was enacted by the city council in 1891. The ordinance imposed fines on both commercial and residential structures that emitted coal smoke. It does not appear to have been very strictly enforced, however, as just two years later a Salt Lake Tribune editorial ran “a general ordinance should cover all the cases [of smoke emission], if there is not such an ordinance even now, resting a dead letter among our laws.” (At the time of its enactment, the ordinance had been published, in full, in the Tribune.) Some progress was made in the following years. Beginning in the 1890s, city planners sought to confine new industrial facilities to the west of the Jordan River, away from the city center; in 1903 they enacted a new, stricter anti-pollution ordinance; and in 1907 a federal court ruled that smelters were responsible for the damage their emissions caused to the crops of neighboring farmers. Nevertheless, smoke remained a major problem—and continued to increase in prominence as a topic of public discourse.

In 1912, the Salt Lake Telegram ran a five-piece editorial, "The Smoke Nuisance." The pieces included covering success stories in other areas "Pittsburgh Fighting for Cleanliness" and "Europe leads in curbing smoke evil". The detrimental effects of smoke pollution to humans, agriculture, and the economy were covered in "Dense Smoke is the Bane of Modern City" and "Millions of Dollars Go Up in Smoke." When decrying the waste caused by the ineffcient fuel source, the prophetic headline "the whole system of power conversion may ultimately be changed" would come to fruition decades in the future. In the last piece, however, "Abatement of Smoke Evil A Big Problem" the focus circled back to focusing on ordinances to mitigate smoke through boiler and furnace operating techniques.

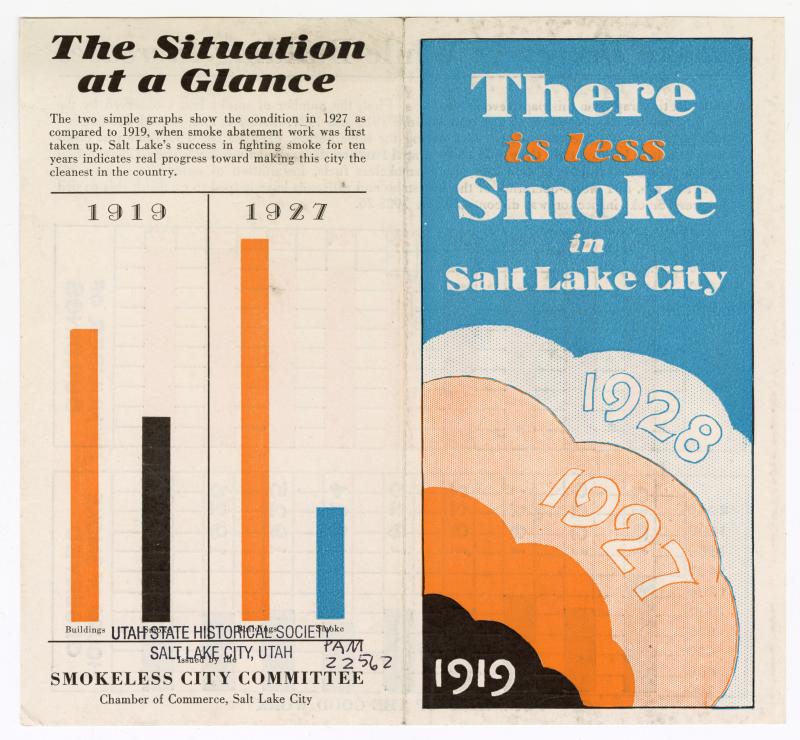

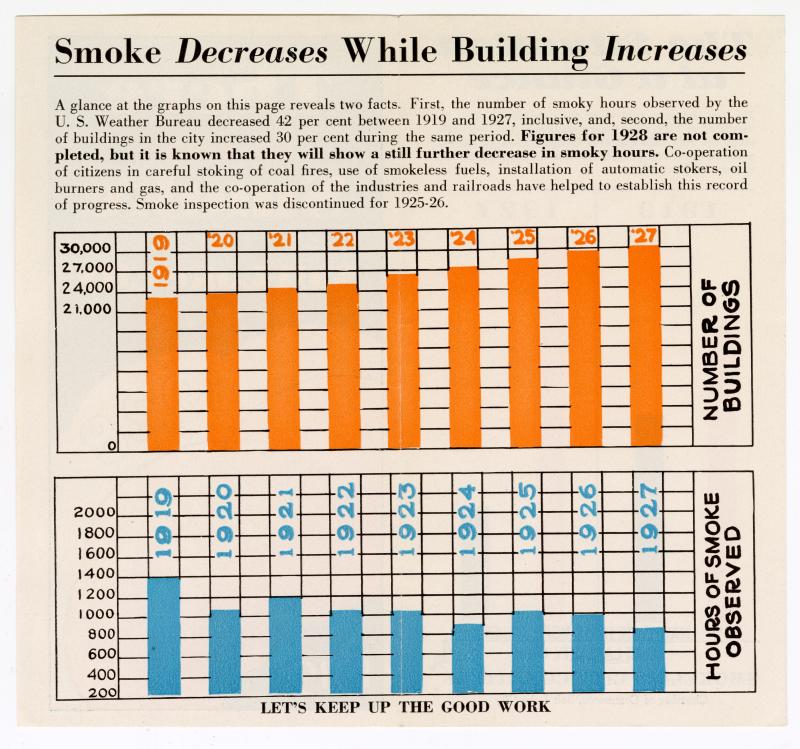

In the aftermath of WWI, Salt Lake City became the site of a major federal study of air pollution. The U.S. Bureau of Mines, in collaboration with Salt Lake City and the University of Utah conducted a comprehensive study that included fuel analysis, emission inventories, air quality monitoring, meteorogical study, and even used an aircraft to collect samples of pollutants at different heights. The study found that industrial pollutants were related to tuberculosis and pneumonia. Although their understanding of vertical temperature profiles and inversion was limited, the study was a major step forward in the scientific understanding of air pollution. With the help of the Bureau of Mines, Salt Lake made significant progress in improving its air quality during the first half of the 1920s. However, despite the positive outlook in the Salt Lake Chamber of Commerce pamphlet below published at the end of the decade, the city cut funding for smoke-abatement efforts after the mid-1920s. The city issued citations for emissions, but the distribution of citations was heavily skewed in favor of manufacturing and railroad interests. According to Historian Ted Moore, apartment buildings and private homes were cited most often, though they produced only twenty-two percent of the smoke, while manufacturers, who produced forty-four percent of the smoke, received only eleven of the eighty-three citations issued between 1921 and 1929, and railroads, which produced nineteen percent of the smoke, received no citations or fines.