Industry Economic Human Landscape

Health

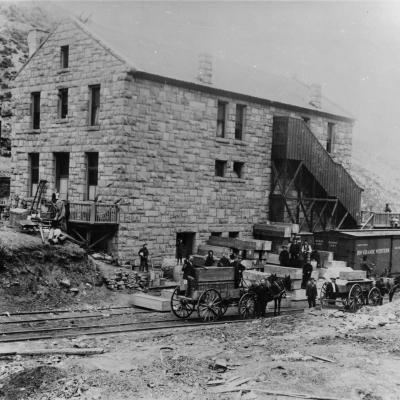

In Special Collections

At the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

Related Resources

In Special Collections

Miner Howard Browne, interviewed in 1983, described the hazardous conditions of working in the mines:

Interviewer [L]: What was it like working in those mines?

Howard Browne [HB]: It was hell. The reason I moved away from there with my family when I started raising a family, moved away from there up here as soon as I could. Because I said, I'm not going to raise my kids up in no coal mine camp. Cause they might want to work in a coal mine. And everytime you walked into a coal mine, you never knew whether you were going to see the daylight again. So many ways to get killed. So. I just said, I ain't going to bring my kids up in a coal mine camp. And, the element in a coal mine camp so many of the people were criminal element and stuff like that. And they -It wasn't a good environment for kids.

L: Did you ever have any close calls yourself?

HB: In the mine? Oh, yes. We were working in the mine that I quit from. We were working the mine that had a vein a of coal about that high...

L: Four feet?

HB: Yeah. And then they had a conveyor there that they were shoveling it into that was taking it to--that would take it to the cars and load it up. But we had to--to get up to the rooms, why we had to bend over like this to get in there. And then when we'd get up in there, why, we'd work on our knees. And we had knee pads and we worked on our knees. But anyway, the main hallage way, the main what they call the main entrance, why, they had blown out enough rock from either the bottom or the top to make enough room so that you could walk along there. And they made it so they could haul this, haul this coal out the hallage way, you know...

But, anyway, I'd worked in the mine long enough to know something about the mine. And I knew that around noon and around 12 o'clock at night is the most dangerous time in a mine. And it was around noon and I kept watching the roof and the floor. And cracks start coming in the roof, in the rock, you know. And then cracks started coming in the floor and that's what they call "working." The mountain was working. And you can tell by the sound and by the way it's popping and everything, so pretty soon, why I grabbed my shovel and started out towards the main hallage way and so, superintendent says, what's the matter?

And I said, well, I'm coming out of there because this thing's coming in pretty quick. And he says, Oh, that won't come in before tomorrow. And I said, Well, tomorrow, I ain't going to be up there. I'm coming on out of here now. And so the other guys that were around there, they said, well, we're coming out too. If Howard's coming out, we're coming out. He said, OK, let's break it off, let's go eat our lunch then. And while we were sitting there eating our lunch, that whole thing came in, covered up all the machinery, the main and the drills. And everything. And I said, you son of a bitch, you tried to get me killed. I said. You can have your mine. This is the last day.

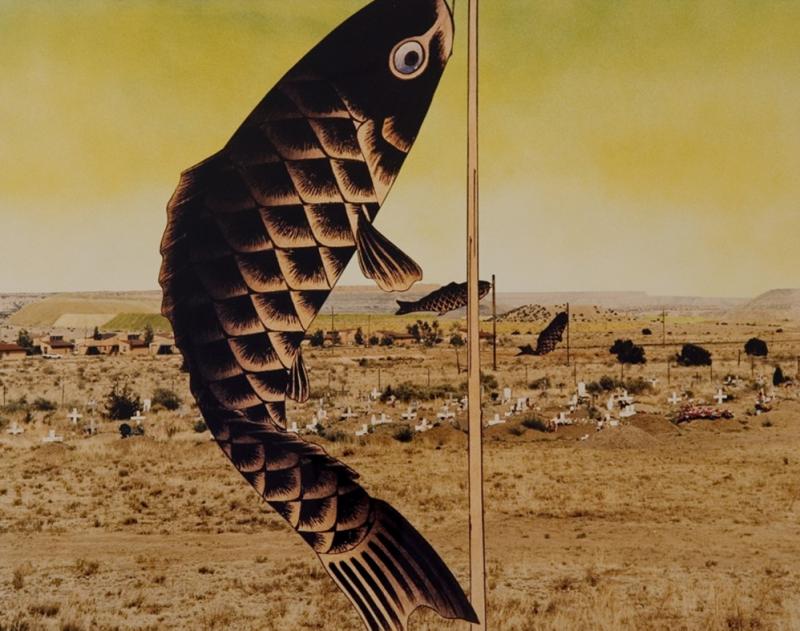

At the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

Patrick Nagatani, Japanese Children’s’ Day Carp Banners, Paguate Village, 1990. UMFA2003.25.29.

Patrick Nagatani, Golden Eagle, United Nuclear Corporation Uranium Mill and Tailings, Churchrock, New Mexico, 1990/1993. UMFA2003.25.30.

On July 16, 1979, uranium waste in United Nuclear Corporation’s tailings pond broke free from its levee. Surpassing Three Mile Island’s disaster just months earlier, the tailings penetrated the surrounding groundwater, pouring millions of gallons of nuclear waste into the Puerco River - the water source for nearby Navajos’ drinking, agriculture, and livestock. It was not the first time that Native Americans’ health was endangered by uranium mining. From the 1940s, Pueblo miners were exposed to uranium contamination as demand for the ore, used for nuclear weapons, surged in the wake of World War II.

Japanese-American Patrick Nagatani’s “Nuclear Enchantment” series examines the American West’s links to atomic energy and weapons development. In these images, the artist, born less than two weeks following the United States’ attack on Hiroshima, denotes the desert as the site of a thriving nuclear industry, which threatens Indigenous peoples while also referencing the internment camps placed in remote regions to contain Japanese and Japanese-American people even as U.S. thirst for nuclear supremacy soared to new heights.

Excerpts from Rain Scald Poetry that explores, through a multiplicity of creative forms, the health impacts of mining on the Diné people. (Tacey Atsitty)

Health and Environmental Impacts of Mining outlines lasting effects of mining on the human body and the earth. (Daniel Mendoza)

An Interview with Tommy Rock An interview about environmental justice with Dr. Tommy Rock, a member of the Navajo Nation, who has conducted research on water quality along the Puerco River, downstream from uranium mill and mining sites. (Tommy Rock)

The Human Element

Lesson Plan, 7th - 12th Grades

Shae Howell

Students will create a physical representation of the assigned body part/body function, using only their own bodies and movement within the group. The movement will take place in front of a sheet, with a light behind the group. The silhouette will be captured on video. There will be several available roles for the production ensuring that all students have an opportunity to participate. The final art piece is a collaborative effort that will reflect the various physical and mental impacts of coal mining on the human body.