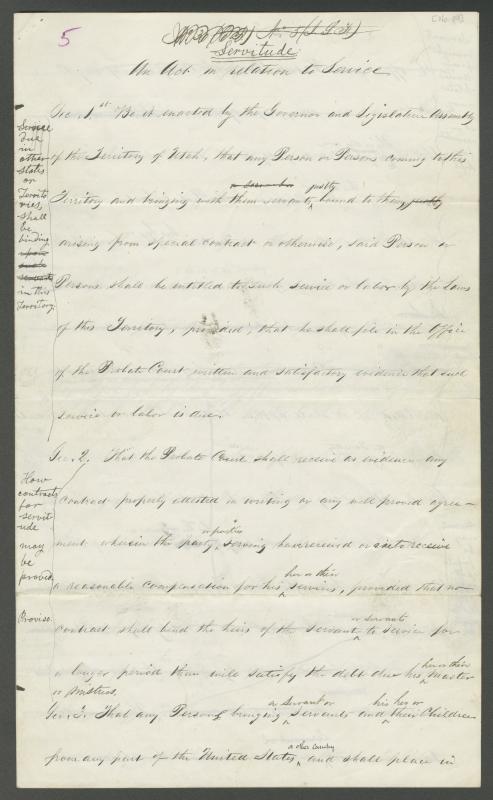

3.3 Utah Territorial Legislature Bill, A Comparison of an early draft and the final version of "An Act In Relation To Service."

A Comparison of an early draft and the final version of “An Act In Relation To Service"

Document Introduction

Territorial legislative records include two versions of “An Act in Relation to Service” which give an indication of some of the changes lawmakers made as they debated the provisions of the bill.[1] Text differing between the two versions is indicated in boldface font. A draft version of the bill is also available at the Church History Library of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (digitally available here). The draft version includes crossed out lines and other such edits which make it possible to better understand changes between original and final versions of the bill. Note Brigham Young’s influence over the final provisions of the bill which stipulate that if a white "master" violates any of the specified sections of the bill the penalty is that “he or she shall forfeit all claim to said servant or servants to the commonwealth.” In other words, if masters violated the terms of An Act in Relation to Service, the penalty for such a violation was that the servant would be set free. Also note Orson Pratt’s influence over Section 3, as lawmakers dropped the clause that would have made “servitude” perpetual.

In general, the various sections of the bill were aimed at regulating masters and honored the “free will and choice” of the servants. The law required written evidence in all cases and specified contractual agreements designed to honor agency. Section 1 established the general principle that contractual servitude was legal in the territory. It required that any persons bringing servants into the territory needed to have a “special contract” attesting to the nature of the “service or labor” that the servant owed. The person claiming the servant’s labor had to provide to a probate judge “written and satisfactory evidence” of that fact. Section 2 was written to govern white indentured servants and similarly expected that the person claiming a servant’s labor had to provide a “contract properly attested in writing or any well proved agreement.” It further stipulated that such servants must receive “reasonable compensation” for their services. Section 3 governed white enslavers who brought Black enslaved people to the territory and required a “certificate of any court of record under seal” in order to prove that the enslaver was entitled to the labor of the enslaved. Moreover it specified that a probate judge had to be satisfied that the enslaved “came into the Territory of their own free will and choice.” This section in particular is difficult to imagine in practice simply because the act of enslavement negated “free will and choice.” Nonetheless, it offers evidence of the middle path between chattel slavery and abolitionism that the legislators attempted to navigate. For those who were enslaved, however, any middle path short of freedom was nothing more than “the other slavery.”

[1] Nathaniel R. Ricks, “A Peculiar Place for the Peculiar Institution: Slavery and Sovereignty in Early Territorial Utah,” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2007), 160-162, offers a similar comparison. The parallel columns below are based on our transcript of the handwritten bills in the Territorial Legislative Record and the draft version of the bill found at the LDS Church History Library. For the original draft of the bill see Territorial Legislative Records, 1851-1894, series 3150, microfilm, reel 1, box 1, folder 55, pages 700-703, UDARS. For the final draft see pages 704-706 of the same source. For the working draft of the bill see, Utah Territory Legislative Assembly Papers, 1851-1872, MS 2919, First Session, 1851-1852, Acts numbers 15-39, box 1, folder 3, CHL.