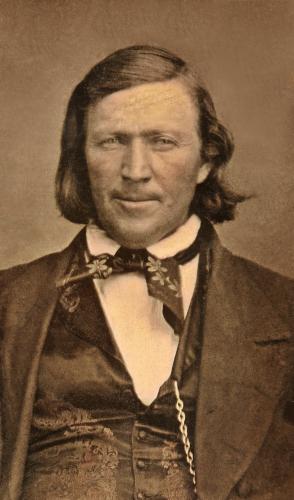

4.2 Brigham Young articulates a racial priesthood restriction, February 5, 1852

Brigham Young gives his most forceful articulation of a racial priesthood restriction in relationship to the election bill, February 5, 1852

Document Introduction

Young’s February 5 speech was delivered in the context of a debate with Orson Pratt over voting rights in Utah Territory. Pratt advocated for black male suffrage and Brigham Young soundly rejected that idea. This new contextual information helps to explain Young’s comparison between priesthood curses and voting rights in Utah Territory.[1]

Young also made it clear that he was the first prophet of the Latter-day Saint restoration to pronounce a racial priesthood restriction. Although Pratt’s speech from the day before does not survive, it is not difficult to imagine Pratt insisting that no other prophet had restricted priesthood from men of Black African descent and that there was no proof that Africans were descendants of Cain. Joseph Smith had in fact sanctioned such ordinations.[2] Young, in any case, made it clear that even if no other “prophet or apostle” said it before, he was saying it now, “Negros are [the] children of Cain” and as such “they can’t bear rule in [the] priesthood.” Young did not claim to draw on Joseph Smith as a precedent for his pronouncement; in fact he made the exact opposite claim. Even if Smith never “spoke it before,” he, Brigham Young, was declaring it now. It is a clear indication that Young was striking out on his own in matters of race and moving the church he led away from open racial ordination toward segregated priesthood. It was a decision that would accumulate precedent over the rest the nineteenth century and the first three quarters of the twentieth century. What Brigham Young began as a priesthood restriction against Black men grew to include a restriction against Black women and men from temple admission (other than to perform proxy baptisms for the dead). It also grew to include a ban against Black women and Black men from missionary service, even though Elijah Able, one of Church’s early Black priesthood holders, served three missions for his chosen faith.[3]

Young’s rationale for the restriction was anchored in the biblical curse of Cain, which created a theological pressure point for his church. Subsequent Latter-day Saint leaders would attempt to relieve that pressure point by inventing alternative justifications which did not violate the fundamental Latter-day Saint tenet of agency. Thus, Young instituted a racial policy which he supported with a corresponding pseudo-doctrine which it would take his church a century and a half to unravel.

Because Watt himself transcribed Young’s February 5 speech into longhand and Woodruff wrote a summary of the speech, three versions survive. We offer LaJean Pursell Carruth’s transcription of Watt’s shorthand in its entirety first. It is the closest version available to what Young said and the most fully developed rationale articulated by a Latter-day Saint prophet/president for a racial priesthood restriction. Next, we place Carruth’s transcription alongside Watt’s transcription of his own shorthand, and Woodruff’s summary in three parallel columns. This again highlights the liberties that Watt sometimes took in refining and modifying the shorthand version as he transcribed. It also demonstrates the remarkable skill Woodruff possessed in capturing the general sentiment of Young’s speech even as it simultaneously lays bare Woodruff’s woeful lack of precision. It should also serve as a caution against relying on Woodruff’s version of the speech in the future when Watt’s verbatim and transcribed versions are now readily available and certainly more accurate.

[1] Brigham Young, February 5, 1852, CR 100 912, Church History Department Pitman Shorthand transcriptions, 2013-2021, Addresses and sermons, 1851-1874, Miscellaneous transcriptions, 1869, 1872, 1889, 1848, 1851-1854, 1859-1863, Utah Territorial Legislature, 1852 January-February, CHL.

[2] W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), chapter 4.

[3] Reeve, Religion of a Different Color, chapter 7; W. Paul Reeve, “Elijah Able,” at CenturyofBlackMormons.org.