5.3 a-g Estate Settlement, David Lewis and two "Indian boys" and an effort to sell an enslaved man named Jerry

The settlement of the estate of David Lewis which included three enslaved people and two “Indian boys” and his widow Duritha Trail Lewis’s effort to sale an enslaved man named Jerry and Brigham Young’s response, 1855-1861

Documents Introduction

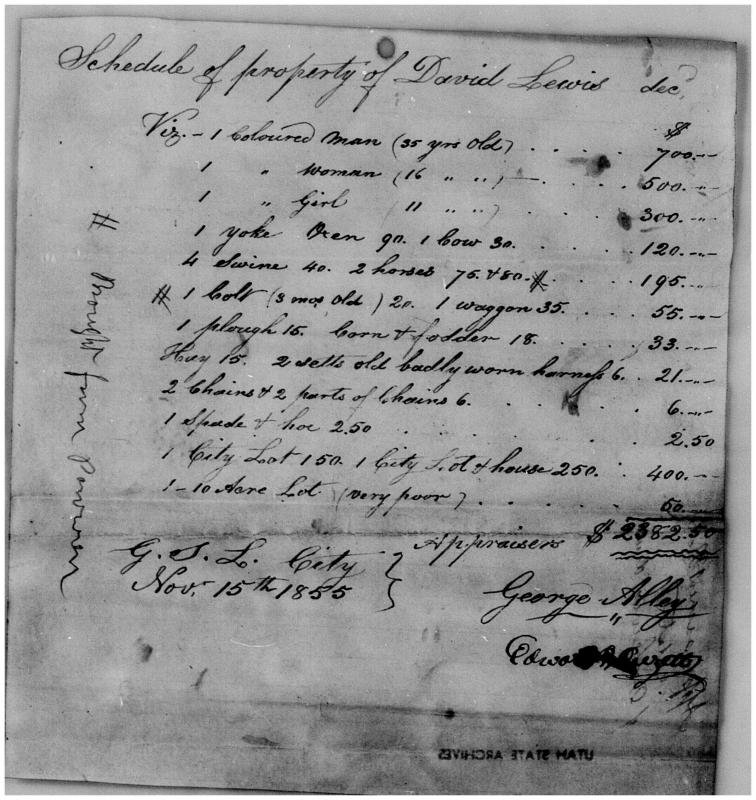

In 1855, Latter-day Saint pioneer David Lewis died while living in Parowan, Utah and serving as a missionary to Native Americans in the region.[1] He left no will and as a result his estate entered probate. The documents that follow trace the settlement of his estate, including the court appointed appraisal of his property (documents 3a, 3b, and 3c). That appraisal listed two Native American boys valued at a total of $95.00 and three “coloured” people: a 35 year old man named Jerry valued at $700.00, a woman named Caroline who was 16 years old and valued at $500.00, and Tampian, a girl age 11 valued at $300.00. They are listed among Lewis’s other property, including his oxen, cow, swine, horses, colt, wagon, corn, and fodder, all given monetary value to be divided among Lewis’s three plural wives and his surviving children.[2] Probate Judge Elias Smith appointed Lewis’s first wife Duritha as administratrix of the estate. Surviving evidence does not indicate the fate of the two Native American boys although they likely remained in Southern Utah with Elizabeth Carson and Margret Pearson, Lewis's plural wives who both subsequently married his brother Tarlton, then a Latter-day Saint bishop in Parowan.

Jerry, Caroline, and Tampian remained with Duritha for the time being. Duritha also remarried but her second marriage did not last. Likely in an effort to shore up her financial stability, she sold Tampian and Caroline to Thomas S. Williams, a Southerner who did not hesitate to try and turn a profit from trading in human beings. Before selling Caroline and Tampian, Duritha went to district court in Salt Lake City to register them, along with Jerry, in an effort to establish her right to sale them (document 3d). It is the last known slave registration in Utah. In it Duritha declares that she inherited her three slaves from her father in Kentucky and that she was their “true and lawful owner.” She claimed to be “entitled to the services of the said Jerry, Caroline, and Tampian during their lives,” and that she made her affidavit so that “they may be registered as Slaves according to the requirements of the Laws of said Territory for life.” The affidavit thus indicates that Lewis considered Jerry, Caroline, and Tampian to be slaves, that she considered their services to be hers “during their lives” and the duration of the enslavement was “for life.”[3]

There are implied messages in Lewis’s affidavit as well. Lewis inherited Jerry, Caroline, and Tampian in Kentucky and eventually took them to Utah with her. They were thus forcibly separated from their families. Caroline and Tampian were taken from their parents and potentially their siblings. Jerry was separated from what family and friends he may have had in Kentucky. Because he was enslaved, he faced prevailing religious and legal strictures against race mixing as well as limited opportunities for social interactions with other African Americans. He was thus denied any real opportunities of forming a family of his own. Their lives were largely shaped by the decisions that white enslaves made.

Even after selling Caroline and Tampian, Lewis apparently continued to struggle financially. By 1860 Brigham Young learned of her desire to sell Jerry as well, information that prompted him to write to Lewis and indicate that if the price were reasonable “I may conclude to purchase him and set him at liberty.”[4] He later learned that Jerry claimed to be free and advised Lewis that under such circumstances it was not wise to try to sale him (documents 3e and 3f).[5] At some point Lewis nonetheless sold or otherwise transferred Jerry to Abraham O. Smoot, then mayor of Salt Lake City. Jerry drowned while enslaved to Smoot as indicated in an article published in the Deseret News (document 3g) the final document in this series.[6] (The newspaper article does not mention Jerry by name, but matching it with a Salt Lake County death record makes it evident that the News article referred to Jerry). Had he survived one more year Jerry would have gained his freedom as a result of the act of Congress that freed enslaved people in all U.S. territories. His freedom would have come, in other words, at the hands of legislators in Washington D.C., not from Lewis or Smoot, his Latter-day Saint enslavers.

[1] “Died,” Deseret News, September 26, 1855, 8.

[2] Schedule of Property of David Lewis, deceased, Utah Territory, Probate Court Records, Salt Lake County, Series 1621, Reel 1, Box 1, Folder 41, Utah Division of Archives and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] Duritha Lewis, Slave Registration, Utah Territory, Third District, Probate Court Records, Series 373, Reel 6, Box 5, Folder 11, Utah Division of Archive and Records Service, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[4] Brigham Young to Duritha Lewis, January 3, 1860, Brigham Young Office Files, CR 1234 1, Reel 27, Box 19, Folder 1, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. We are indebted to Ardis E. Parshall for sharing this letter with us.

[5] Brigham Young to Duritha Lewis, March 31, 1860, Brigham Young Office Files, CR 1234 1, Reel 27, Box 19, Folder 5, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. We are indebted to Ardis E. Parshall for sharing this letter with us.

[6] “Drowned,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), June 19, 1861, 8.