Becoming a Research Center, 1973-1991

When Alfred C. Emery was appointed President of the University of Utah in 1971, the campus had quieted down. Though tensions still smoldered at the University of Utah and elsewhere, many students were directing their energy elsewhere. The University of Utah, recognizing that the future would be high-tech, took steps to ensure the school would be at the forefront of research into computers, medical devices, and other industries. In 1965, Governor Calvin Rampton commissioned a five-year study to determine the best use of almost 600 acres of land that had been declared surplus by Fort Douglas. In 1968, the concept of a research park was first advanced, meeting with the approval of all concerned. In 1970, 320 acres of the Fort Douglas military reservation were set aside specifically for the creation of a research park.

The land was obtained by 1970 and work began soon after that. The goal of the University of Utah’s Research Park was not only to create space for research companies, but to attract new high-tech industries to Utah and to the University. In 1973, David Pierpont Gardner became the next President of the University of Utah, and at once began to expand the research role. The same year that President Gardner was inaugurated, the University of Utah ranked twenty-sixth in the nation in the amount of federal funds received, which meant that the university had arrived as a major research institution.The institutional push towards research was not without conflict. Vice President Brigham Madsen tried to have a certain part of the acreage set aside for establishment of sorely needed married student housing, but this idea was met with disapproval from the business community and the governor, and the married student housing had to be built elsewhere.

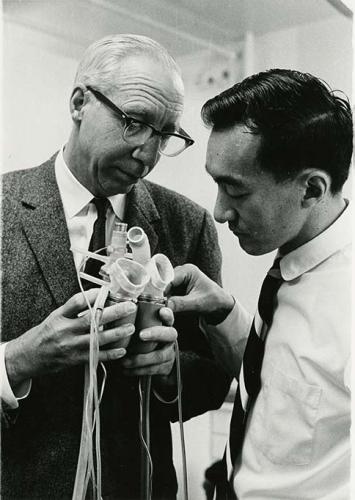

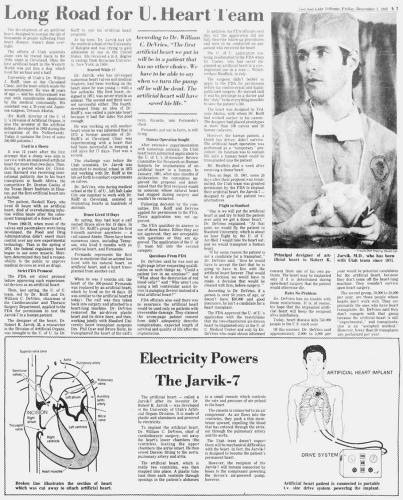

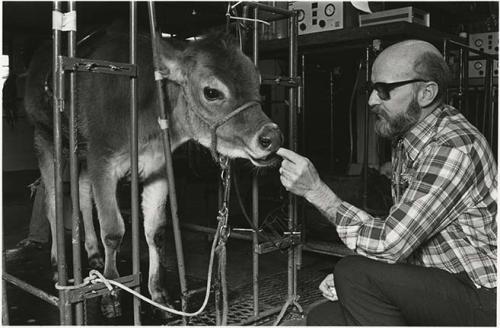

Several of the early successes of the University of Utah’s new focus on research came from investments made in the 1960s. In 1967, the university recruited Dr. Willem Kolff from the Cleveland Clinic in Ohio to direct a new Division of Artificial Organs and the Institute for Biomedical Engineering. Since his invention of the first dialysis machine while surviving the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands during World War 2, Dr. Kolff had grown an international reputation as the “Father of Artificial Organs.” Dr. Kolff brought initial research he had begun on an artificial heart from Ohio, as well as members of a team that included Dr. Clifford Kwan-Gett. In Utah, he assembled a team of researchers and doctors that included Don B. Olsen, William DeVries, and Robert Jarvik. After numerous successful artificial heart transplants into calves, in 1982, a team implanted a total artificial heart into Dr. Barney Clark, a Seattle dentist who volunteered for the experiment. Dr. Clark lived for three months with the device. While the Institute for Biomedical Engineering’s focus ultimately shifted away from a total artificial heart, this pioneering work laid the groundwork for the University of Utah hospital’s Lung and Heart/Lung Transplant programs as well as continuing research into innovative devices devoted to supporting failing organs.

Elsewhere, in the new University of Utah School of Computing, David C. Evans and Ivan Sutherland recruited top talent in engineering and computer science to both the faculty and the student body. The two professors formed Evans & Sutherland, a company which became the world leader in computer simulators for aerospace from its home in the Research Park. University of Utah students made swift and significant breakthroughs in computer graphics, such as the Utah Teapot, an early example of 3-D modeling created by Martin Newell. Other notable alumni included John Warnock, who co-founded Adobe in 1982; Edwin Catmull, co-founder of Pixar; Henri Gouraud, inventor of Gouraud shading in computer graphics; and many others. This pioneering work formed a foundation that was built upon in many directions, including degrees in graphic design and game design.

In 1971, the Spencer S. Eccles Health Sciences Library was completed and dedicated in order to provide dedicated support to medical research, publishing, and education. In 1972, the university established the first Biomedical Informatics program within the School of Medicine, an outgrowth of the Biomedical Informatics Department founded by Dr. Homer Warner in 1964. The faculty and graduates of this field provided advancement in electronic health record software as well as computerized research into genealogical and genetic health science information. The University of Utah Hospital became a world leader in treatment of burns and other trauma, and the university supported the Primary Children's Hospital in becoming a nationally recognized teaching hospital as well. By the time Dr. Chase Peterson of the University of Utah Medical Center replaced David Gardner as president of the university in 1983, income from patents and commercial licenses on inventions from the university's faculty amounted to millions of dollars. The only blot on this happy landscape during the 1980s was the claim by two scientists, Pons and Fleischman, that they had discovered a cold fusion process. This was loudly proclaimed as the invention of the decade, but when the two could not reproduce their results, the University of Utah’s reputation was briefly tarnished.

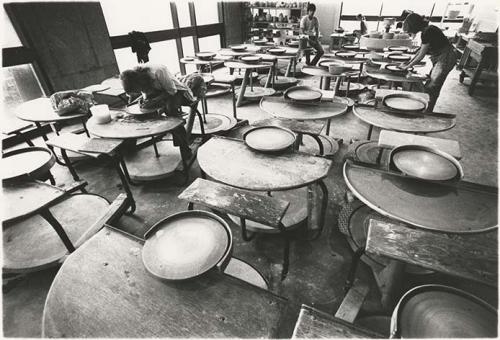

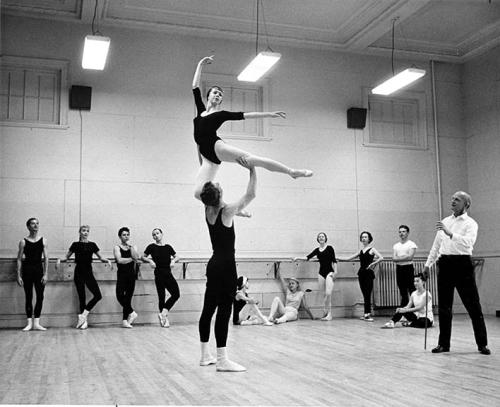

The university’s long history of liberal arts education was challenged by the investment in science as administrators struggled to balance a mix of teaching that included liberal arts and humanities alongside technical research. However, even as the University of Utah gained international standing as a research center, many of its arts programs continued to gain prestige. In the early 1970s, the Department of Theatre added a BFA in musical theatre, a program that built on the College of Fine Arts’ existing strengths in music and dance. Graduate training in various aspects of theatre, music, and dance proliferated, and numerous graduates transitioned into careers with the expert training they received. In 1989 a new dance facility, the Alice Sheets Marriott Center for Dance, was opened; this, along with nationally recognized faculty members, helped cement the Modern Dance and Ballet programs as some of the best in the United States. Other programs in the College of Fine Arts–such as Music, Theatre, and Studio Art–also emerged as competitive degrees in the American West. Despite the reputation built by generations of skilled professors and students, in 1988, the Department of Theatre received numerous degree cuts, including the BFA and MFA in Musical Theatre.

As always, life on campus continued as normal despite the successes and failures of the scientists at Research Park. Additions were constructed on the Chemistry Building and the Alumni House, the Olpin Union Building, and several of the older buildings on President's Circle were renovated. The Student Services Building was completed, bringing together under one roof and in one central campus location all departments and services needed by students from registration to financial aid. Student enrollment reached over 25,000, a far cry from the handful of scholars who met in the Pack House in the 1850s.

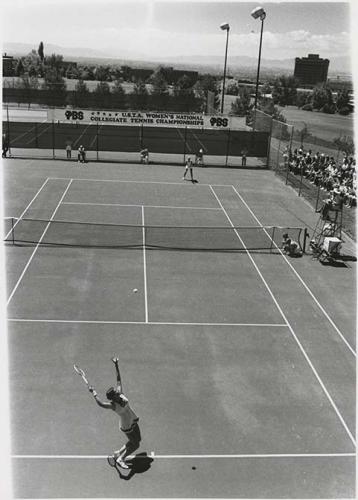

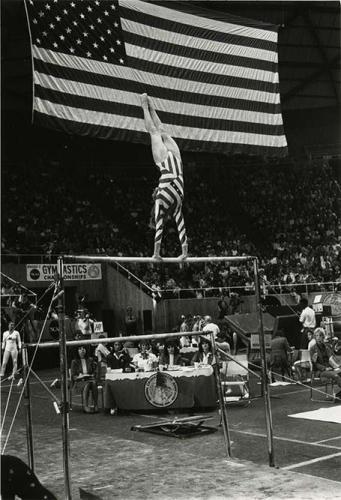

The 1970s and 1980s were also decades of growth and success in athletics as the University of Utah emerged as a force in several different athletic fields. Since the Ski Team’s formation in the 1940s it had performed well, but the program leapt into dominance with the 1974 hiring of Pat Miller, who became head coach in 1976. Miller quickly led the women’s team to an NCAA championship in 1978, with a championship for the men following in 1981. In 1983, skiing became a coed sport, and the Ski Team won five more national championships in the 1980s; numerous talented alumni went on to compete on the national stage of the Olympics. In 1981, the University of Utah recruited alumni F.D. Robbins–a star collegiate tennis player who had gone on to play professional tennis through the 1970s–to serve as assistant tennis coach; he soon helped head coach Greg Holmes propel the University of Utah to the 1983 NCAA Singles Championship and an All-America selection. In 1987, Robbins became head coach and under his leadership the University of Utah tennis team qualified for five NCAA championships between 1987 and 1997. The University of Utah women's gymnastics team, under coach Greg Marsden, won an unprecedented six straight national titles from 1981-1986.

By the beginning of the 1990s, the investment into research, technology, and an expanded campus built the University of Utah into a leading institution in numerous fields. More than just one of the oldest educational institutions in the state, the University of Utah had become the flagship of Utah's higher education system, a school that welcomed the new age with pride and confidence.