The Great Depression and World War II, 1930-1945

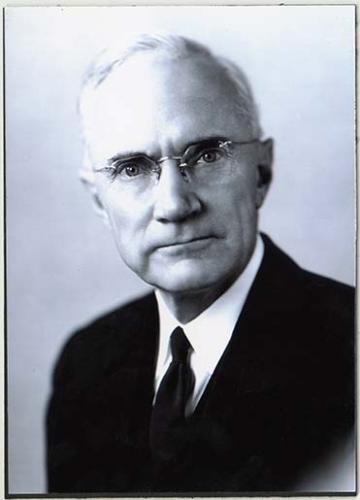

At the end of the 1920s, the University of Utah seemed poised for a period of expansion and growth under the confident leadership of Dr. George Thomas. Then, in October 1929, the stock market crashed, triggering the Great Depression. The University of Utah was impacted in various ways: students and their families could no longer afford tuition and books; the state legislature, faced with lower tax revenues, cut the university's budget; and many banks which had financial dealings with the university were forced to close. Faculty salaries were frozen, contracts were not fulfilled, and, for the first time, enrollment dropped. But with hard work by President Thomas, and with the aid of federal work programs, the university was able to reverse these trends and overcome the effects of the Great Depression.

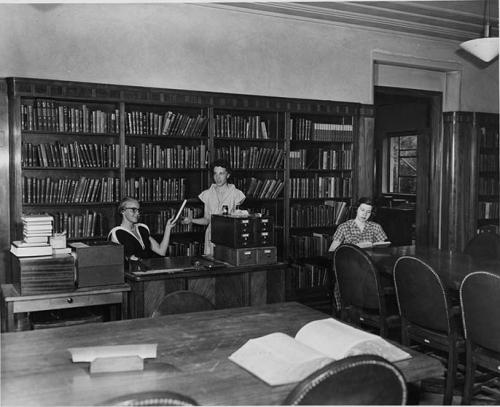

In 1934, the University of Utah received another 61 acres of land from Fort Douglas. Construction on campus, which had been suspended at the height of the economic emergency, was resumed using funds and labor provided by the federal government’s Works Progress Administration (WPA). Soon the sounds of construction echoed across campus. Not all construction on the campus was for noble academic halls: land was leveled and landscaped; a sprinkler system was installed for lawns; several miles of curb and gutter were completed; campus roads were extended, leveled, and paved; new gas, steam, and power lines were laid; and a new culinary water well was drilled on the south end of the campus, which soon became known as the Fountain of Ute. For years the university’s library was moved from one building to another, never having a purpose-built structure to call home. This was rectified in 1935 by the opening of the George Thomas Library, named in honor of President Thomas. The new library was built by WPA workers and contained 124,000 volumes. Even that wasn't the end of the building program: Carlson Hall, a dormitory for women, was opened in 1938 and the Einar Nielsen Fieldhouse held its dedication game in 1940.

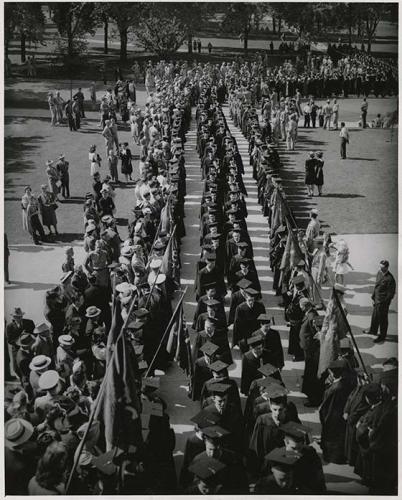

The academic position of the university constantly improved under President Thomas as well. Enrollment, after a slump in the early 1930s, picked back up again, and a Phi Beta Kappa chapter was installed in 1935. In 1936, the Salt Lake County Director of Welfare requested that the University of Utah train more workers capable of dealing with the social impact of the Great Depression, and the next year, the Graduate School of Social Work was organized. The 1930s was a time of transition, as several faculty members who had been with the university since the 1890s retired or passed away, including Andrew Love Neff, Frederick W. Reynolds, Frederick J. Pack, and Maud May Babcock. This changing of the guard culminated when President Thomas announced his retirement, effective November 15, 1941. He was replaced by Dr. Leroy E. Cowles, the newly-appointed Dean of Education.

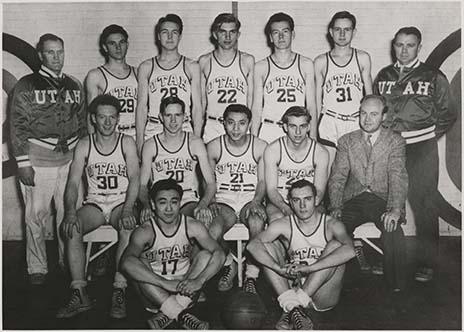

Athletics also flourished. In 1925, the University of Utah hired Ike J. Armstrong, who served as general coach for various sports and developed football, track and field, wrestling, swimming, and other programs in his 25 years at the University of Utah. In 1938, the football team played in its first bowl game, defeating the University of New Mexico in the Sun Bowl. Under the leadership of Coach Theron S. Parmelee, who had been hired in 1921, tennis thrived, winning numerous state championships and gaining national recognition. Coach Vadal Peterson, hired in 1927, developed a successful basketball program. In 1936-1937, the University of Utah Ski Team organized and began competing–despite the fact that it was not officially supported by the university and, until funding was given in 1945, it was not eligible to participate in intercollegiate competitions.

Just as things were back on track, another world crisis reached the University of Utah. By the end of 1940, the United States increased their support for the Allies, and many Americans anticipated they would soon be drawn into the war raging in Europe and Asia. The University of Utah Regents took steps to prepare for the possibility of war, unwilling to be caught unawares as they had been twenty years earlier. Throughout the 1930s, participation in the ROTC program rose steadily, and in 1939, the Regents signed a military contract to establish the Air School, which added coursework to allow prospective pilots to finish all their ground courses at the university. In 1940, the university began participating in the federal National Defense Training Program, which provided instruction for civilians and funds to establish additional engineering and defense training for college-aged men.

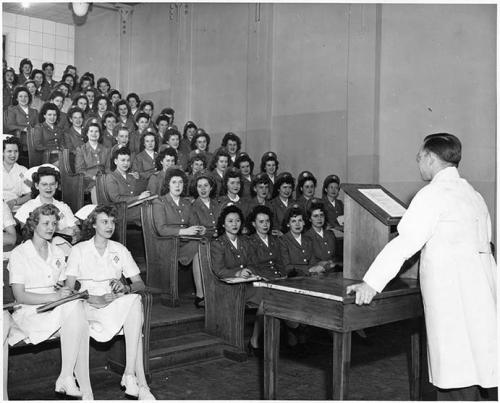

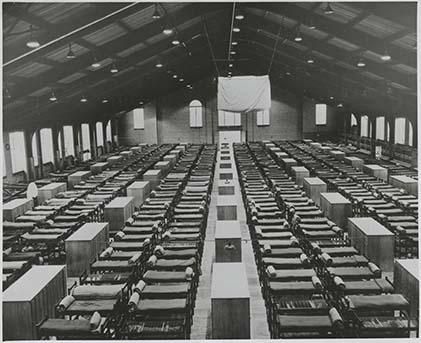

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese Navy Air Service attacked the United States naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, prompting the United States to declare war on Japan. President Cowles established faculty and administrative committees to deal with a host of new problems, which included: air raid precautions; an influx of men in uniform; and the loss of many students and some faculty to the armed services. The United States had enacted the first peacetime draft, the Selective Training and Service Act, on September 16, 1940, and it was amended and expanded with the declaration of war. The immediate impact on the University of Utah was a drop in enrollment of almost twenty percent. Responding to military requests, the university began offering courses in meteorology and photography. The Army, having filled up the buildings at Fort Douglas, leased office space in the Park Building for the duration of the war. In 1943, the University activated the Army Specialized Training Program, or ASTP, which taught basic engineering, languages, medicine and dentistry to about 1,100 men on campus. Due to a lack of housing, the newly-built Nielsen Fieldhouse was repurposed into a dormitory for soldiers being trained in medicine.

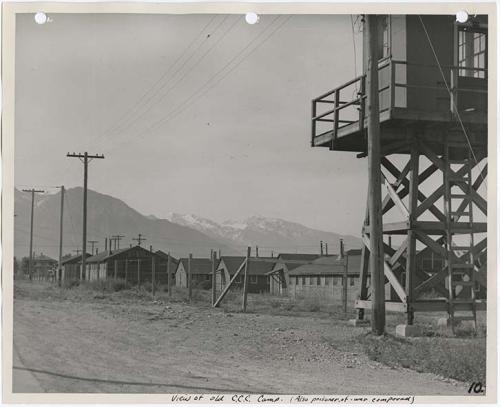

At the same time, the basic work of the university, crowded though it was, went on. Women enrolled in numbers higher than ever before, helping offset some of the loss of male students to war industries and the armed services. In 1942, the Board of Regents approved the enrollment of Japanese American young adults who had been born in Utah or were incarcerated at the Topaz War Relocation Center near Delta, Utah and able to petition for educational release; however, the Board capped enrollment at 150. The Medical School changed to a four-quarter system, allowing doctors to complete their training in three years instead of four, and after much debate, the program was expanded to four years in 1944. In 1942, in response to wartime demand, the university established a three-year program in nursing education, originally located in the School of Education. Requirements and curriculum were adapted to the needs of a nation in war by granting diplomas to seniors who were called up for active service, allowing high school students to register early, and allowing credit to be granted for some military training.

The Graduate Program was expanded to allow the granting of doctorate degrees in 1945. Even the non-academic aspects of life at the University somehow went on. In 1944, the University of Utah basketball team won the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) championship game, and defeated a strong St. John's team in a Red Cross charity game the next night. Among the championship team was Wataru “Wat” Misaka, one of the Japanese Americans who had been permitted to enroll at the University of Utah; after graduation, Misaka became the first Asian American and first non-white athlete to play in the National Basketball Association (NBA).

Though the University of Utah faced numerous hurdles since its creation, the back-to-back crises of the Great Depression and a second World War were among the most challenging. However, the university applied the lessons its administrators, faculty, and staff had learned in the tumult of World War I to prepare and lead the campus through periods of national and global instability. During an economic depression and war, the University of Utah proved that it could endure and remain the premier institution of higher education in the state of Utah, ready for the years of rapid growth on the horizon.