The New U of U, 1892-1914

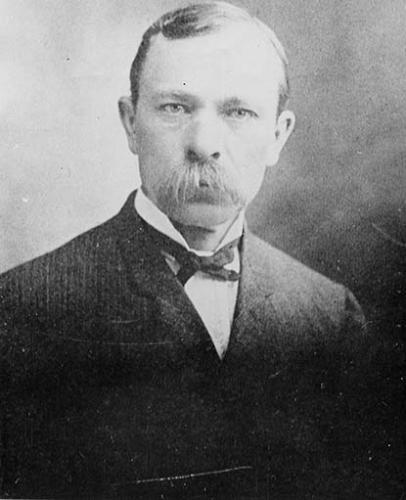

The end of the 19th century found the newly-renamed University of Utah on the verge of great changes, both in size and location. In 1894, the U.S. Congress granted the University of Utah sixty acres of land on the East Bench of Salt Lake City. This land had been part of Fort Douglas since it was founded in 1862, but as the United States military concluded its conflicts with Indigenous nations in the 1890s, the Army increasingly considered military posts such as Fort Douglas as surplus. James E. Talmage replaced Joseph T. Kingsbury as president of the university in 1894, and served for three years. During this period, the university faced yet another threat to its existence. At the Constitutional Convention in 1895, legislators introduced a motion that would have closed the University of Utah and consolidated it with the State Agricultural College in Logan. The motion was defeated, and an article was placed in the state's constitution that established two separate schools. In 1897, Dr. Kingsbury was once again appointed as president, a position he would hold for the next two decades as he helped usher the school into the 20th century.

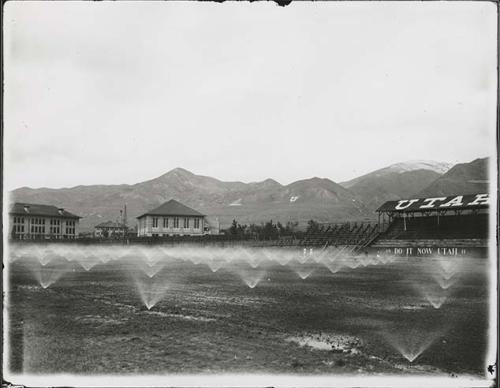

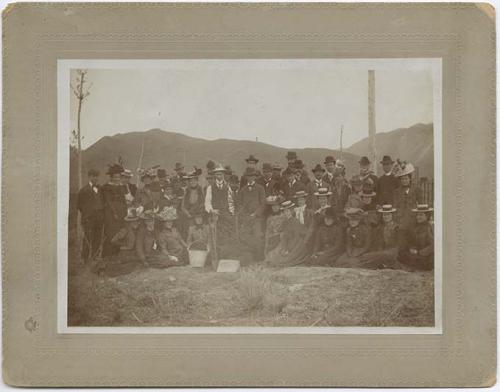

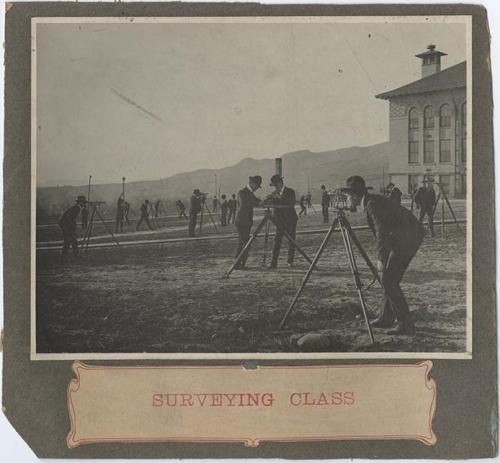

In 1896, Utah became a state. Two years later, the Board of Regents voted to move the University of Utah to the new East Bench location. The next year, the state legislature appropriated $200,000 for buildings on the new campus. Utah architect Richard K. A. Kletting, who designed the original Saltair Resort and the Utah State Capitol Building, was commissioned to create a plan for the campus. Engineering students surveyed the grounds and prepared a map of the new location. Students also helped landscape the campus by planting trees on Arbor Day; this became a campus tradition that continued for a number of years. The university planned to construct four new buildings for the growing campus: the Physical Science Building, the Liberal Arts Building, the Normal School, and a museum. The appropriation only covered the first three buildings, and they were completed by the time registration opened on October 1, 1900. On December 19, 1901, the Physical Science building was partially destroyed in a fire, but quick action by students, professors, and a regiment of soldiers from Fort Douglas saved books, furnishings, football uniforms, and much else from the flames. The building was rebuilt and reopened by the start of the 1902-1903 school year. In 1904, the campus continued to grow when a further 32 acres were obtained from Fort Douglas. Meanwhile, enrollment at the University of Utah was also growing: in 1900 there were 183 students and by 1910 enrollment was over 1,500.

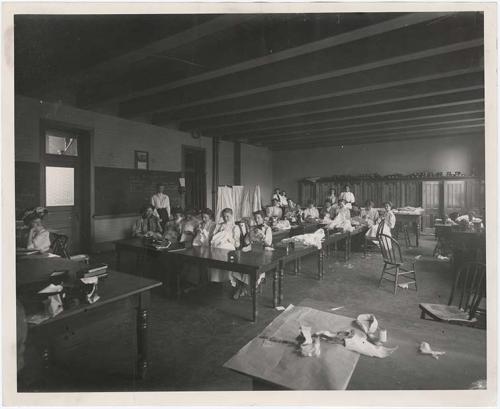

To respond to the increased number of students–and in the face of competition for students from the Agricultural College in Logan, where attendance was less expensive–the Utah State Legislature increased the University of Utah’s funding. Upon his death in 1900, Dr. John R. Park bequeathed his entire fortune and his library to the university. The increasing number of students led the university’s administration to establish entrance requirements, first for the School of Arts and Sciences, and then for the whole university. The increase in students also led to the growth and professionalization of a number of degree programs, a process that began with the reorganization of the university into departments in 1893 and continued into the 20th century.

The State School of Mines was established in 1901 and renamed the School of Mines and Engineering in 1913, and in 1905 the Department of Biology began offering two-year medical courses. In 1912, the medical program established a separate two-year Medical School with Dr. Ralph V. Chamberlin as the dean. The first professionally trained librarian, Esther H. Nelson, was appointed in 1906. In 1909, the name of the Normal School was changed to the State School of Education, and the Law School was formally established in 1913, along with the Department of Mining and Metallurgical Research and the U.S. Bureau of Mines Experiment Station. The new administration building, later named in honor of Dr. Park, was completed in 1914, as were the Civil Engineering, Mechanics, and Gymnasium buildings. The library, now comprised of almost 13,000 volumes, was moved to the Park Building.

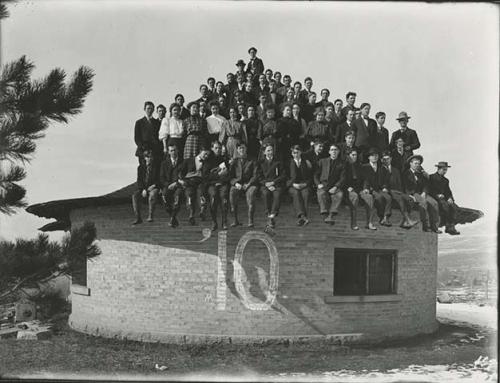

With the growth of the student body came increases in student organizations and activities. The Associated Students of the University of Utah, after an earlier false start, was established in 1901. The Varsity Glee Club, established in the 1890s, was joined by a Girls Glee Club in 1902. Other music clubs followed, and by 1908, they were consolidated into a Musical Society. Debating societies, literary clubs, and other student organizations flourished on the new campus. A number of fraternities and professional societies marked their beginnings during this period, and the first Junior Prom was held in 1905.

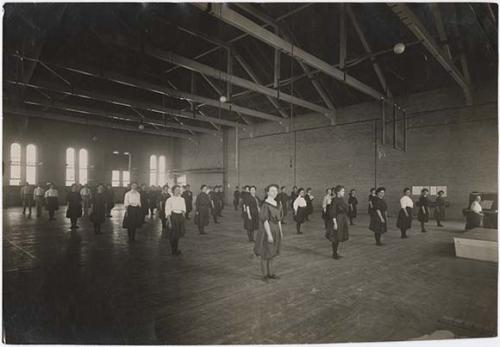

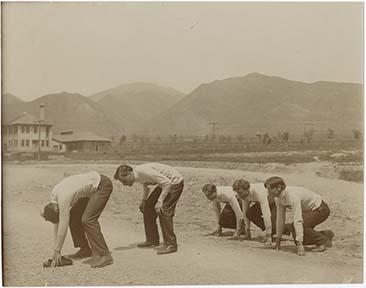

One person, Professor Maud May Babcock, helped establish both athletics and theater at the University of Utah. Babcock joined the university in 1892 as the first female faculty member and put on her first public theater production in 1893; she soon founded the Department of Physical Education and the Department of Speech. Despite the interest in physical education among faculty and students, organized sports were not initially funded, and the university suffered a series of embarrassing defeats at the hands of the Salt Lake High School football team. In May, 1900, the University of Utah hired Harvey Holmes, the first paid head football coach and the first coach to stay with the team for more than one season. In 1904, Holmes and the team wrote “A Utah Man,” which became the school’s official fight song. A symbol of the University of Utah, the “Block U” on the hillside north of the campus, was built in 1907, and that same year, the first yearbook, The Utonian, was published.

But not all the news from the University of Utah cast the school in a positive light. In 1914, a controversy over academic freedom shook the university to its foundations. Four faculty members were demoted or not rehired because they allowed a graduation speaker to criticize the influence of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints on the University of Utah. The students and faculty mobilized, and protests and meetings were held. The University of Utah was the subject of the first investigation by the newly-founded American Association of University Professors, which found the administration guilty of firing or demoting faculty members for trivial causes. By the time the controversy was finally resolved in 1915, twenty-one faculty members–one-third of the faculty–resigned in protest, including Byron Cummings, the first Dean of Arts and Sciences. The controversy also led to the resignation of President Joseph T. Kingsbury in January 1916. In contrast to the hope and growth that had characterized the end of the 19th century, the University of Utah faced an uncertain future in the first years of the 20th century.