World War I and the Roaring 20's, 1915-1929

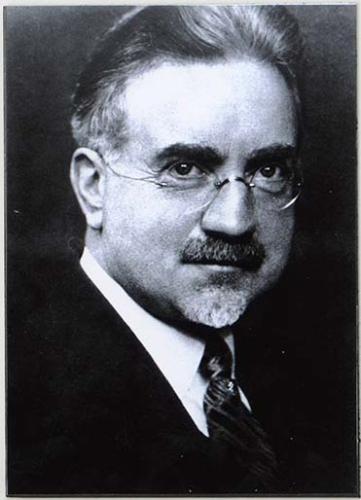

Dr. John A. Widtsoe was inaugurated as President of the University of Utah in January 1916. He had already built a distinguished career as a scientist and educator at the Utah State Agricultural College, where he developed expertise on dry-land farming and irrigation. Despite some grumblings from the faculty at the University of Utah about the method of his hiring, Widtsoe soon settled in as an effective and respected leader. However, he soon faced another crisis: the possibility that the United States would be drawn into the war that had overtaken Europe. When the war started in August 1914, it caused a stir of interest on campus, but most Utahns supported a position of neutrality. As national groups increasingly advocated for intervention in the war, in 1916 General Richard W. Young, a graduate of the University of Utah, proposed that the university adopt a training program for military service. When this proposal was not adopted, Young brought a plan before the Board of Regents to coordinate military instruction for students with Fort Douglas. While this proposal was also refused, the University of Utah offered free attendance to events and waived course registration for Army and Navy soldiers stationed in Salt Lake City.

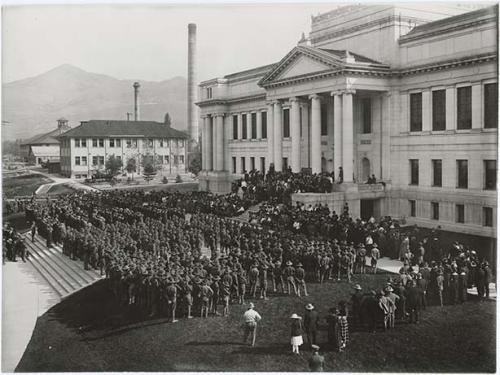

In late 1916 and early 1917, student and faculty support of war preparedness rose, and in March 1917, a student group petitioned the Board of Regents to establish military training on campus. In response, in April 1917, the Board of Regents established a Department of Military Science and Tactics, one week before the United States declared war on Germany. The lack of time to prepare resulted in great confusion as the university scrambled to put itself on a war-time footing. The university made military drills for male students compulsory, even though there was no one from the Army to lead the students in the necessary military evolutions until the end of the school year, and students practiced using dummy wooden guns. Students were urged to volunteer time on farms to increase food production or to join active military service. Faculty agreed to give full course credit to all students who left for military service, and seniors who enlisted were granted their diplomas. The rush to prepare for war was so distracting that final exams were dropped that year. Many female students and faculty responded enthusiastically to the call and went to work with the local Red Cross unit preparing bandages, knitting sweaters for soldiers, and helping with food production

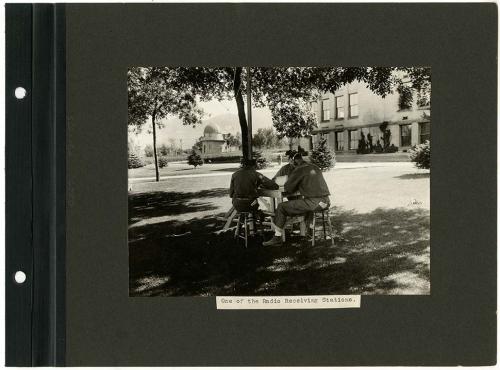

The United States implemented a military draft that went into effect on August 30, 1918, and in order to train draftees, the University of Utah was designated a training camp for the SATC, or Student Army Training Corps, in October 1918. Despite all the work of the past year in preparing the university for war, faculty and staff had been expecting a reduced year of enrollment, and they struggled with the sudden responsibility of training, educating, feeding, and housing over 1,200 men. Lines of communication and chains of command were muddled, and students enrolled in the training program were too tired to attend their regular classes; when they did, it was common to see them slumped over their chairs, sound asleep. The SATC experiment proved to be a fiasco.

To make matters much worse, in late 1918, the Spanish Influenza epidemic reached the Intermountain West. The epidemic, which ultimately took more lives than all the battle casualties of World War I, struck crowded Army camps especially hard. The University of Utah responded by canceling classes and sending all students, including the cadets, home. The Army ordered the cadets back to their barracks, with the result that twenty-eight of them died of the disease, in addition to fifteen other students. Then on November 11, 1918, an armistice was signed between the warring powers, and suddenly the SATC was superfluous. By the end of the year all cadets had been demobilized and, as suddenly as the war preparations had escalated, the university was expected to return to a state of normalcy.

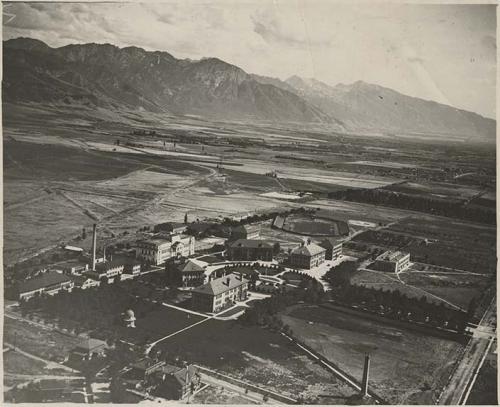

Programs that were suspended during the war crisis were resumed. By 1918, a pharmacy program was added to the Medical School, the School of Business was organized, and the Observatory building was constructed. That same year, the four quarter academic year was introduced, which endured until 1998. Two buildings that were originally supposed to be built as barracks—the Life Sciences and Stewart buildings—were instead completed for academic use in 1920. Nor were the lessons of the SATC lost: the United States War Department established ROTC, or Reserve Officers’ Training Course, in 1920, and the University of Utah opted to participate in the program to ensure preparedness in future national crises.

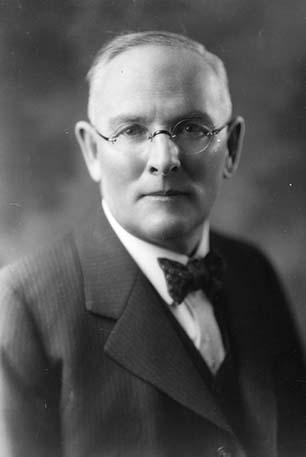

In 1921, President Widtsoe resigned as president to accept a position in the governing body of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. He was replaced by George Thomas in April 1922. Dr. Thomas was an economics scholar, a background that suited him to guide the university during the decades between two world wars. One of President Thomas’ visions was that the University of Utah, while it would never be one of the largest schools in the country, could be one of the best. With that goal in mind, President Thomas raised admission standards, abolished the high school program, and generally improved the level of scholarship at the university. The student body supported President Thomas in these endeavors, with the result that the University of Utah was admitted into the Association of American Universities and a chapter of Phi Kappa Phi was established.

Under President Thomas, the number of students enrolled jumped dramatically. By 1932, there were 3,600 students at the university, an increase of 78 percent. Similar increases took place within the faculty: by the end of the 1920s there were 182 faculty members, 54 of whom held PhDs. Notable faculty who joined the University of Utah during this period included: artist James T. Harwood; Herbert Maw, future governor of Utah; botanist Walter P. Cottam; Gail Plummer, a speech instructor and theater director; anthropologist and Aztec scholar Charles Dibble; and William Behle, professor of biology and distinguished ornithologist.

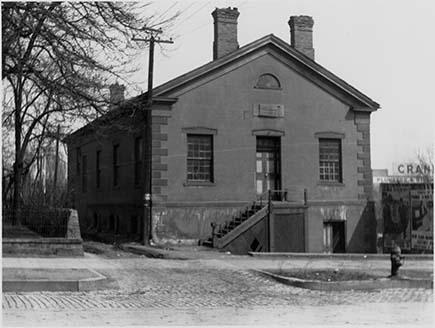

With the rise in student enrollment, many aspects of student life saw increased growth and activity. The 1920s saw an explosion of Greek life on campus, and both social and service fraternities and sororities were established on campus. In 1922, the University of Utah’s theater group, the Varsity Players, lost the venue where they put on shows when the historic Social Hall was demolished by the city. Despite the loss of their venue, theater thrived at the University of Utah through both formal education and drama clubs independently organized by students. Similarly, music education grew in the 1920s, and students formed glee clubs and pep bands to perform on tours and at campus events. Due to students’ persistent interest and participation in music and theater throughout the 1920s, the university decided to construct a “University Theatre”, soon named Kingsbury Hall, on campus to consolidate and provide a home for theater, opera, and music.

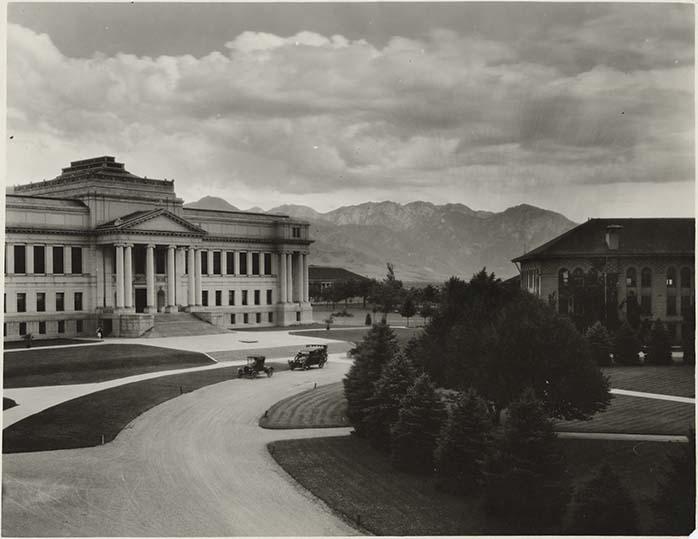

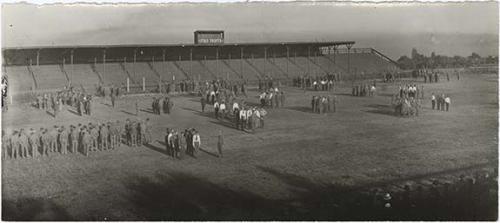

President Thomas oversaw a period of expansion of the campus. Buildings constructed during the 1920s included: Gardner Hall, constructed to serve as the Student Union, begun in 1925 and completed in 1931; the Stadium, ready for its first game in October 1927; theater venue Kingsbury Hall, dedicated in 1930; and a number of smaller improvements. Renovations were carried out in the Medical Building, the Gymnasium, the Mechanical Arts Building, and the Park Building. At the end of the 1920s, President George Thomas could look back on a solid decade of expansion and improvement, but he was about to face a national crisis as devastating to his presidency as the Great War had been to his predecessor.