William "Sam Joe" Harvey

Life

William (sometimes “Sam” or “Sam Joe”) Harvey arrived in Salt Lake City in early August 1883. Little is known about his life prior to that point. He came from Pueblo, Colorado. He was an Army veteran, about 35 years old, and tall with an athletic build. After arriving in Utah, Harvey set up a bootblack stand on Main Street in downtown Salt Lake City. He was described as irritable and some worried about his mental health.

Lynching

On August 25, 1883, a white mob of up to 2,000 people gathered in front of the city jail in Salt Lake City, Utah and brutally hanged a Black man named William H. Harvey in a violent, public spectacle lynching. Also referred to as "Sam Joe" Harvey, Mr. Harvey was arrested and jailed after he was accused of shooting and killing the city’s police chief, but was lynched before he could stand trial. After his lynching, despite known police complicity and thousands of mob participants and spectators, no one was held accountable for lynching William H. "Sam Joe" Harvey.

During this era, white press coverage did little to uncover personal details about Black victims of racial terror. These reporting and documentation practices by white press reflected the heightened value placed on white lives and the blatant indifference towards the recognition, or even accurate identification, of Black people killed through racial violence and terror. The details of Mr. Harvey’s life and background were sparsely documented in white press accounts following his lynching, and no remarks or testimony from Mr. Harvey was recorded. His name was identified as William H. Harvey, Sam Joe Harvey, and Joe Harvey in various press accounts. The Deseret News of Salt Lake City, however, reported that a Black man who identified himself as Mr. Harvey’s half-brother said Mr. Harvey’s name by birth was Joseph Samuels, and that he was a native of Louisiana in his mid-thirties. The Salt Lake Daily Herald also indicated that Mr. Harvey had once served in the army. Mr. Harvey had lived in Pueblo, Colorado, until his search for employment brought him to Salt Lake City, where he set up an unsuccessful shoeshine stand on South Main Street.

According to news reports, in the early afternoon of August 25, Mr. Harvey entered a Black-owned restaurant on South Main Street and told the owner that he was struggling financially, expressing fear that he would "freeze to death" by winter unless he secured employment. The restaurant owner reportedly offered Mr. Harvey a job making $2 a day on his farm, which was located twelve miles away from the city. When Mr. Harvey expressed dissatisfaction that the job was so far away, an argument erupted between the two men. Newspapers reported that the restaurant owner grabbed Mr. Harvey in an attempt to forcefully remove him from the restaurant. Mr. Harvey drew a weapon, then put it away, and left the restaurant. After Mr. Harvey left, the owner called the police. When the chief of police and the local watermaster arrived on the scene, newspapers claimed that Mr. Harvey fired a gun, killing the police chief and wounding the watermaster. Other officers eventually arrived on the scene and took Mr. Harvey into custody.

Like many Black people accused of violence committed against a white person, Mr. Harvey swiftly faced threats of racial terror violence from white Salt Lake City residents. Though Mr. Harvey was entitled to his constitutional right to due process, the officers also participated in the terroristic violence, despite their legal obligation to protect him. After arresting Mr. Harvey and taking him to the police headquarters in the City Hall, the officers beat Mr. Harvey severely. One officer reportedly struck him between the eyes, knocking him to the ground, and others immediately joined in on the assault, repeatedly kicking and beating Mr. Harvey with billy clubs, brass knuckles, and shackles before carrying him to the jail. Outside City Hall, a growing mob of white people began chanting "Hang the son of a b–!" and demanded that Mr. Harvey be turned over to them. During this era of racial terror, it was not uncommon for lynch mobs to seize their victims from jails, prisons, courtrooms, or out of the hands of police. Though they were armed, police rarely used force to resist white lynch mobs intent on killing Black people. As in the case of Mr. Harvey, use of force by the police was more likely to be directed at the lynching victim than at the lynch mob. Rather than resist the mob and prevent the lynching, The Salt Lake Tribune reported that the police officers complied and "gave up their victim to the crowd, which proceeded to hang him." The Tribune would later insist that the police officers’ actions in Mr. Harvey’s lynching were especially extreme:

"Mobs have hung men repeatedly, but never before what we remember of have the policemen who had the prisoner in charge, first beaten him into half insensibility and then turned him over to the mob."

When Mr. Harvey was in the mob’s hands, they called for a rope and mercilessly stomped and beat Mr. Harvey "until his face was a mass of blood and bruises." When a noose was placed over his head, the mob gave out an exciting roar of approval and Mr. Harvey was hanged from a roof-beam of a shed near the jail. When Mr. Harvey tried to hold on to the rope to avoid strangling to death, a mob participant climbed on top of a nearby carriage and kicked Mr. Harvey’s hands until his grip gave way, killing him. The mob, which had grown from hundreds to as many as two thousand, "gathered around and gazed at the revolting spectacle" of Mr. Harvey’s hanged body, but his death did not end the lynching. Instead, the white lynch mob cut down Mr. Harvey’s lifeless body and dragged his corpse through the streets of Salt Lake City. The public torture of Mr. Harvey was not only intended to inflict brutal harm on him but also to send a message of white dominance and to reinforce the racial caste system of the era, in which white lives held heightened value while the lives of Black people held little or none.

As the mob was dragging Mr. Harvey’s mangled corpse down State Street, the mayor intervened and succeeded in breaking up the mob. That afternoon, an inquest was convened and a coroner’s jury heard testimony from witnesses. Despite the public lynching by unmasked citizens and complicit police officers, the jury returned a verdict that Mr. Harvey "came to his death by means of hanging with a rope by an infuriated mob whose names were to the jury unknown."

After the lynching of Mr. Harvey, white Salt Lake City officials and the local white press overwhelmingly sympathized with the mob, failed to hold the police officers who were complicit in Mr. Harvey’s lynching accountable, and dehumanized Mr. Harvey in order to further justify the lynching. The Salt Lake Daily Herald called Mr. Harvey a "dog" and reported that Mr. Harvey "was nothing more or less than a wild beast in human form." Rather than hold the mob accountable, the Herald acquiesced to the mob’s lawlessness, stating that "they acted as human nature generally prompts under such circumstances, and cannot be greatly blamed."

When Latter-day Saint leader George Q. Cannon learned of Harvey’s lynching, he wrote in his journal that “an infuriated mob had seized the negro and hung him, and his body was afterwards dragged through the streets. I was greatly pained at this news,” Cannon recorded. “The hanging of the negro, and the treatment of his corps[e] afterwards, shocked me greatly. I have a deep-rooted and invincible hatred of mobocracy in every form,” he said. “I cannot justify it.” His point of comparison was the mob that killed the founding leaders of his faith, Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum. The mob that killed those two men had concluded that “powder and ball” were the solution to the so called “Mormon problem.” It was a precedent that Cannon found “abhorrent.” In the wake of Harvey’s death he thus concluded, “Of all people in the world we [Latter-day Saints] have every reason to stand by the [rule of] law.”

By refusing to hold lynch mobs accountable, white officials, community members, and newspapers only served to embolden the perpetrators of racial violence and encourage the reign of terror that would continue to target Black Americans for nearly a century following the Civil War, resulting in more than 4,000 documented lynchings of Black men, women, and children.

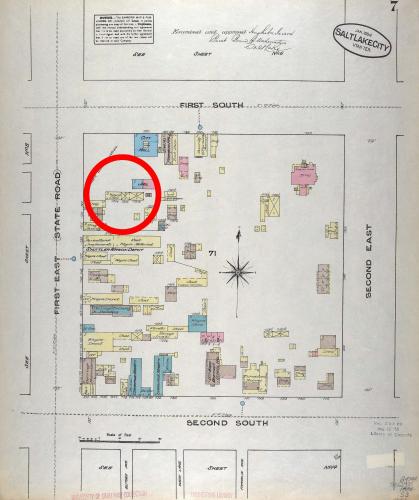

Lynching Site

The plot of land occupied by the Old City Hall and the jail house in 1883 sat at the northwest corner of 100 South and State Street. That location is currently occupied by the Wallace F. Bennett Federal Building.

Sources

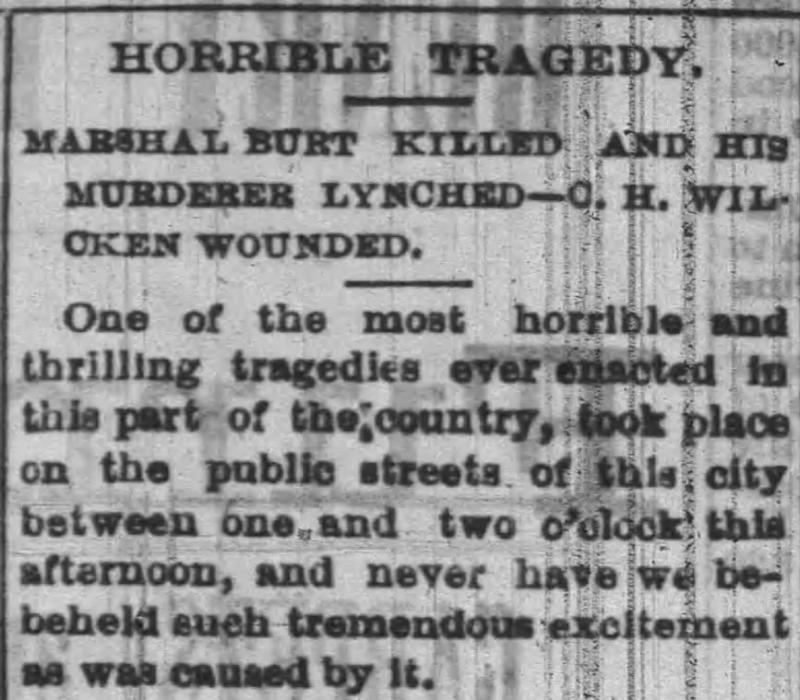

"Horrible Tragedy," Deseret Evening News, 25 August 1883, 5.

George Q. Cannon, Journal, 25 August 1883, The Journal of George Q. Cannon, Church Historian's Press, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

John Morgan, Journal, 25 August 1883, MS 1479, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

“The Lynching Yesterday," Salt Lake Tribune, 26 August 1883, 2.

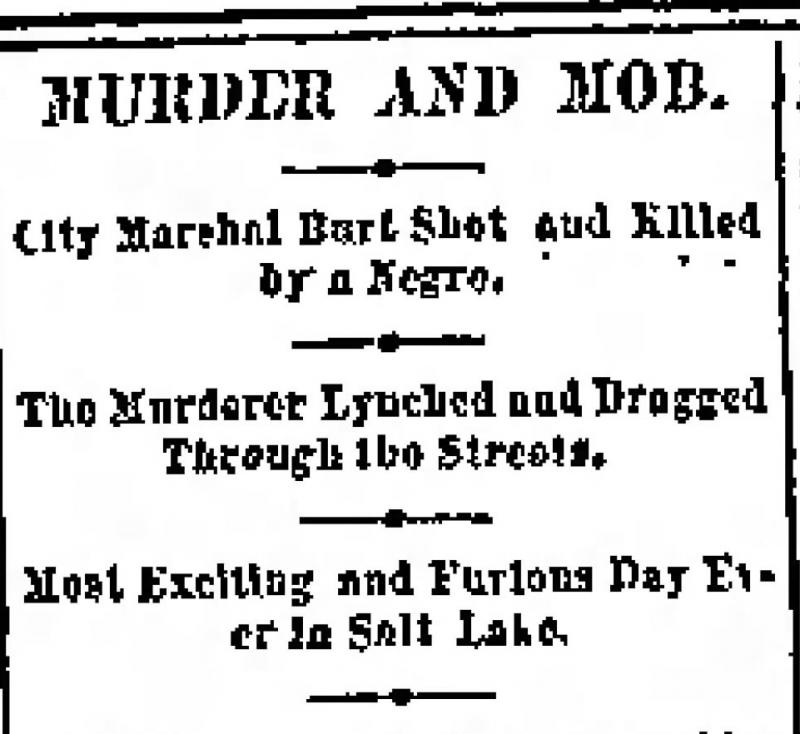

"Murder and Mob," Salt Lake Tribune, 26 August 1883, 6.

"Judge Lynch," Salt Lake Daily Herald, 26 August 1883, 4.

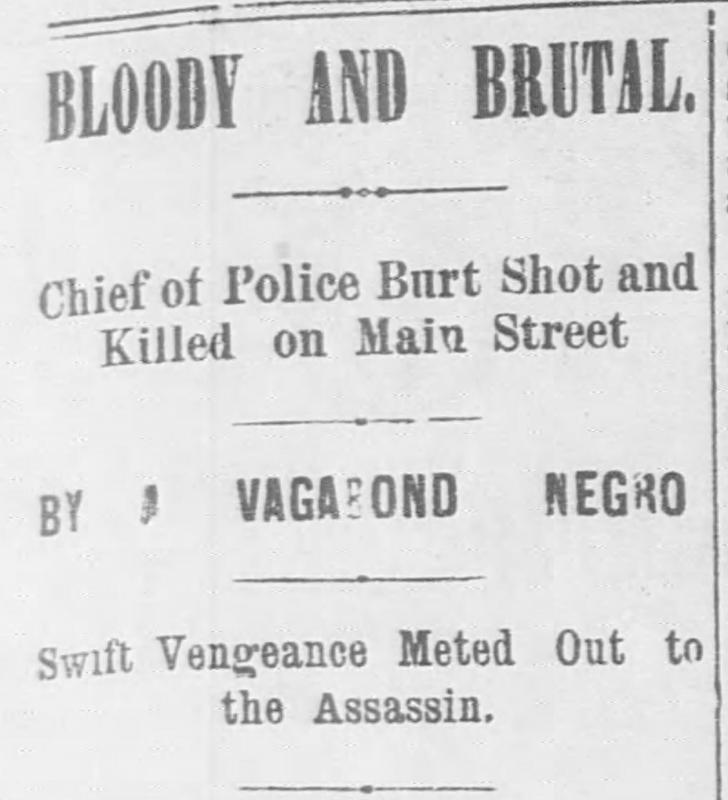

“Bloody and Brutal," Salt Lake Daily Herald, 26 August 1883, 9.

"The Coroner's Jury," Salt Lake Daily Herald, 26 August 1883, 12.

"A Step too far in Slander," Deseret News, 27 August 1883, 2.

"The Murder," Salt Lake Tribune, 28 August 1883, 4.

"Horrible Tragedy," Deseret Weekly News, 29 August 1883, 12.

"Marshal Burt," Deseret Weekly News, 29 August 1883, 12-13.

"The Uncovered Skeleton," Deseret Evening News, 31 October 1883, 3.

"Officer Paid for Bravery with Life in Arresting Shooting Bootblack," Salt Lake Telegram, 12 August 1941, 7.

Gerlach, Larry R. (1985), “Vengeance vs. the Law: The Lynching of Sam Joe Harvey in Salt Lake City”, in Community Development in the American West: Past and Present Nineteenth and Twentieth Century Frontiers, edited by Jessie L. Embry and Howard A. Christy. Provo, UT: Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, chapter 9.

Brad Westwood and Cassandra Clark, "African Americans and Salt Lake's West Side: Part One," Salt Lake West Side Stories, Utah State Historical Society.