Response to Anti-Polygamy Legislation

Morrill Act (1862)

Polygamy was a source of tension between the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the U.S. government for several decades until a series of laws, culminating with the Edmunds-Tucker Act of 1887, ended the practice. The Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act of 1862 first criminalized polygamy in U.S. territories, but during the height of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln had neither the funds nor the will to enforce the Act. One year after Lincoln signed the Morrill Act into law, Brigham Young sent Thomas B. H. Stenhouse, a noted journalist and member of the Church, to Washington to gauge Lincoln’s intentions on enforcing anti-bigamy laws. Lincoln reportedly told Stenhouse, “When I was a boy on the farm in Illinois there was a great deal of timber on the farm which we had to clear away. Occasionally we would come to a log which had fallen down. It was too hard to split, too wet to burn, and too heavy to move, so we plowed around it. [That’s what I intend to do with the Mormons.] You go back and tell Brigham Young that if he will let me alone I will let him alone.”[1]

Without intervention from the federal government, polygamous marriages increased in Utah over the next twenty years.[2] When the Utah Legislature became the second territory to grant women the right to vote in 1870, many assumed that woman would vote against the “barbarous” practice of polygamy.[3] Women in Utah, however, staunchly defended polygamy in print and at the ballot box. Until 1890, Woman's Exponent was a frequent defender of polygamy (perhaps unsurprising as both editors and many contributors were plural wives) and gave stinging rebukes to critics of plural marriage. The article below, "Ignorance and Bigotry," shows one such unsparing response to a San Francisco newspaper, which had called polygamy a "canker upon the body of Christendom" and asserted that "tyranny and fanasticism go hand in hand in Utah."[4]

Evarts Circular (1879), Edmunds Act (1882), and Edmunds-Tucker Act (1887)

The federal government increasingly enforced anti-bigamy laws in the 1870s. Congress heard reports of contested Territorial elections dominated by Mormon voting blocs, saw national media decry the practice of plural marriage as "Asiatic barbarism," and generally understood Utah to be a threat to a newly reunified nation recently engaged with federal centralization. One such centralization project was the consolidation of immigration control by the federal government. In the 1870s, 80s, and 90s, the federal government established the nation's first federal immigration laws which shifted jurisdiction away from state control. As part of this effort, the U.S. government identified immigration as the source for polygamy's growth. In 1879, Secretary of State William Evarts sent out a circular that urged foreign governments to restrict polygamous emigration which was "largely based upon and promoted by these accessions from Europe, drawn mainly from the ignorant classes, who are easily influenced by the double appeal to their passions and their poverty, held out in the flattering picture of a home in the fertile and prosperous region where Mormonism has established its material seat."[5]

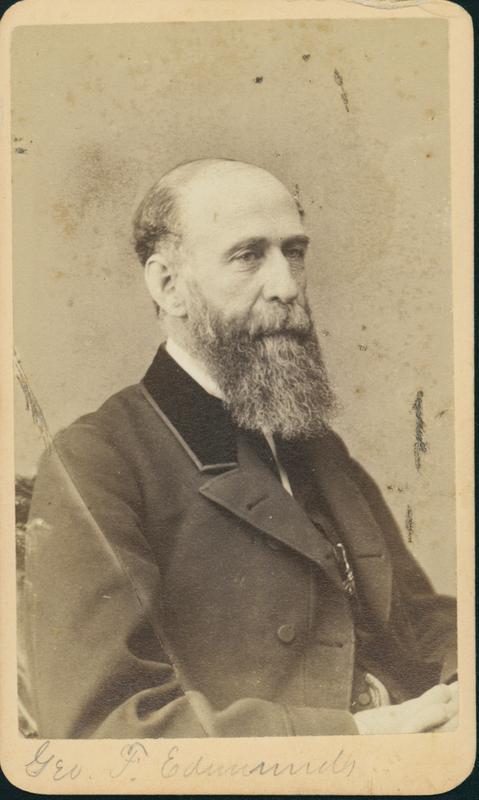

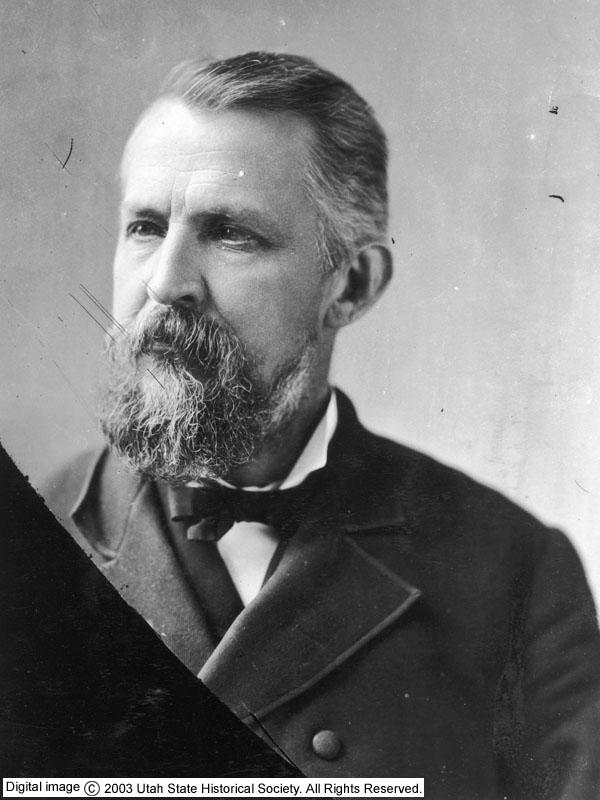

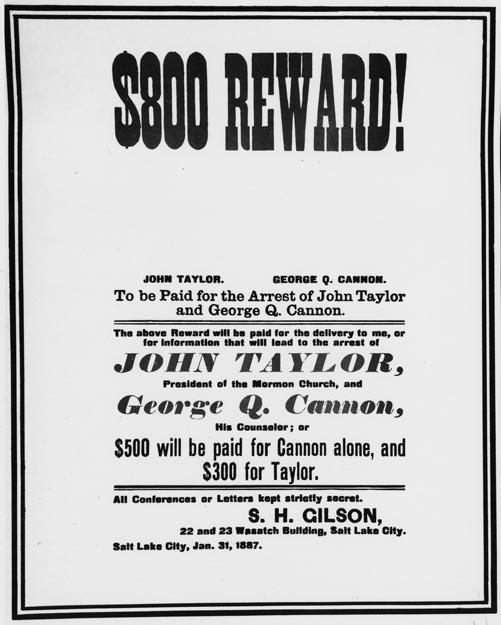

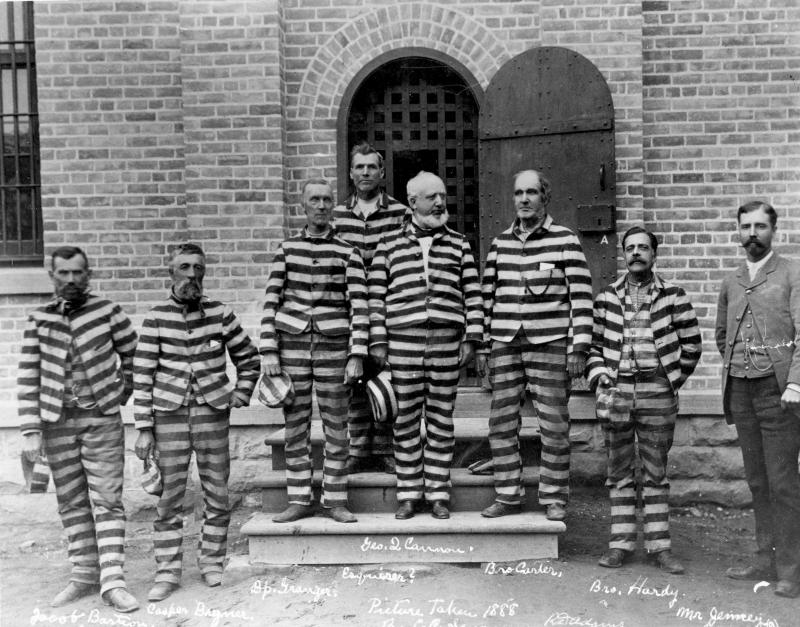

The failure of the Evarts Circular to stop polygamous immigration, along with presidential and congressional pressure, prompted further legislative action against Mormon polygamy. The Edmunds Act of 1882 made polygamy a felony and took away the right to vote, hold office, or serve on a jury from anyone engaged in a polygamous relationship. While the Edmunds Act was the first serious effort to suppress polygamy through criminalization and the denial of citizenship rights, the 1887 Edmunds-Tucker Act dealt an even more severe blow to the Church: disincorporating it, seizing its property, and dismantling its Perpetual Emigrating Fund. Individuals were required to take an anti-polygamy oath prior to being able to vote, hold public office, or serve on a jury. Local judges were replaced with federally appointed judges to ensure the Act was enforced and women were required to testify against their husbands in court. Finally, the Edmunds-Tucker Act disenfranchised all women in Utah.

The Edmunds-Tucker Act languished in Congress for over a year before it was passed, giving contributors to Woman's Exponent ample opportunity for reporting and persuasion. The February 1, 1886 issue (see below) included impassioned commentary and the language of the Edmunds-Tucker Act reprinted in full.

The writers of Woman's Exponent viewed anti-bigamy laws as a direct attack on their families, communities, and religion. Aware of the perception of Utah women as enslaved, uneducated, and at the mercy of a demeaning patriarchal system, they used the newspaper as a venue for shaping public opinion and presenting a different view of Utah women as empowered, erudite, and influential. Much like those in the contemporaneous suffragette movement, the women of the Woman's Exponent were their own best defenders, and proved their mettle by organizing indignation meetings, controlling their narrative, and championing women’s suffrage. The Exponent characterized Edmunds-Tucker and its predecessors as “wicked and cruel laws to destroy our religion, to break up our families, and bring ruin, desolation, and woe to our happy homes.”

Ultimately, after one last Supreme Court challenge by the Church failed in Mormon Church v. United States (1890), the U.S. government succeeded in pressuring the Church to abandon the practice of polygamy. Four months later, the Church, under the leadership of President Wilford Woodruff, published a manifesto banning plural marriage, ultimately paving the way for Utah statehood in 1896.

After the passage of anti-polygamy legislation, it seems that polygamy became less culturally important for the readers and writers of the Woman's Exponent and it consequently was mentioned less frequently. Between 1872 and 1880, the paper contained 104 mentions of polygamy, which increased to 164 between 1880 and 1890. In the subsequent 24 years until the last issue of Woman's Exponent, there were only a total of 18 mentions of polygamy.

The issue of the Woman's Exponent below was issued in the wake of Edmunds-Tucker passing the U.S. House of Representatives in January 1887. In her comments on the legislation, editor Emmeline B. Wells writes, "The taking away of the suffrage from women after they have voted for seventeen years, is an inexcusable wrong; and more especially so in men, who profess to be the friends of women, and to protect their rights and 'guard their best interests in the family and the home', and all that kind of sentimentalism, that means nothing at all, but is a lot of political rubbish and bombast, that all sensible women perfectly understand."[6]

[1] Woodger, Mary Jane. “Abraham Lincoln and the Mormons.” In Civil War Saints, edited by Kenneth L. Alford, 61–81. Provo, UT: BYU Religious Studies Center, 2012. https://rsc.byu.edu/archived/civil-war-saints/abraham-lincoln-and-mormons.

[2] Daynes, Kathryn M. More Wives than One: Transformation of the Mormon Marriage System, 1840-1910. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2001. See pages 91-115.

[3] Gordon, Sarah Barringer. The Mormon Question: Polygamy and Constitutional Conflict in Nineteenth-Century America. Studies in Legal History. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

[4] Greene, Louisa Lula. “Ignorance and Bigamy.” Woman’s Exponent. August 15, 1872. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/ark:/87278/s6b328d3.

[5] "Diplomatic Correspondence, Circular No. 10, August 9, 1879, Sent to Diplomatic and Consular Officers of the United States," Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States 1879, 11-12. See Parshall, Ardis E. "The Very Real Consequences of the American Government's 1879 Effort to Bar Mormon Immigration." Keepapitchinin, the Mormon History Blog. August 10, 2016. http://www.keepapitchinin.org/2016/08/10/the-very-real-consequences-of-the-american-governments-1879-effort-to-bar-mormon-immigration/, and Reeve, W. Paul. Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness. New York: Oxford University Press, 2015.

[6] Wells, Emmeline B. “Comments on Passage of Edmunds-Tucker.” Woman’s Exponent. February 15, 1887. https://newspapers.lib.utah.edu/details?id=23724755.

To cite this webpage, use the following citation:

Cummings, Rebekah, and Jeff Turner. “Anti-Polygamy Legislation.” Woman’s Exponent Project, 2019. https://exhibits.lib.utah.edu/s/womanexponent/page/edmunds-tucker-act.

Photos on this page courtesy the Utah State Historical Society, used with permission.