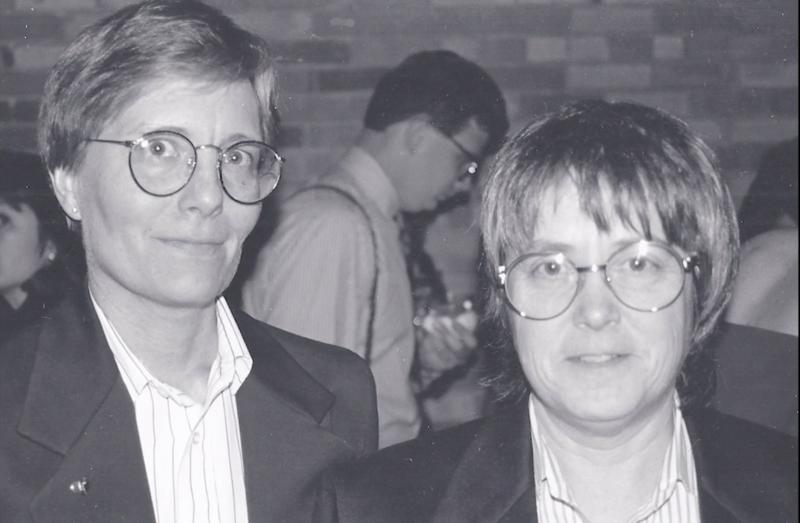

Kristen Ries and Maggie Snyder

While the HIV/AIDS epidemic of the 1980s provoked controversy throughout the nation, looking at the disease’s impact within the notoriously conservative, family-centered state of Utah offers a unique perspective. Utah’s social environment wound tightly around the values of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, as members made up over 67% of the state’s population in 1980 and rose to almost 72% by 1990. Coupled with a universal fear of spreading HIV/AIDS, the Church’s harsh disapproval of homosexuality stigmatized the disease and created a hostile attitude toward those affected statewide.

The spread of HIV/AIDS caught the attention of Dr. Kristen Ries long before the disease had a name. Ries had just moved to Utah, and having specialized in infectious diseases, she kept tabs on its development. As many other healthcare providers turned a blind eye toward the disease, Ries eventually became the first – and for a while, the only – doctor to see HIV patients in Utah. By the mid-1980s, Dr. Ries had treated over 90% of Utah’s total HIV patients in the first 20 years of the epidemic. Ries’s private practice was based out of Holy Cross Hospital (later Salt Lake Regional Medical Center) with the help of the Sisters of the Holy Cross.

As the number of cases grew, her workload became unmanageable; she decided assistance was necessary. Since there were no other doctors willing to help in her controversial practice, Ries found a dedicated Holy Cross nurse named Maggie Snyder and helped her go to school to become a physician’s assistant. Together, Ries and Snyder cared for thousands of people with HIV/AIDS and fostered an accepting, supportive environment during a time in which patients’ humanity were being otherwise dismissed. Their practice grew and gained support, allowing them to retire confidently by the early 2010s. During the early years of their professional collaboration, Kristen and Maggie fell in love. The two are still life partners today.

“It was always like one name: Kris and Maggie” - Nikki Boyer

“[Kristen and Maggie] showed me that the very best medical care must be accompanied by the very biggest compassionate heart if it was to truly be effective.”

- Linda Bellemore, Holy Cross Sister

Compassion Over Capital

Kristen Ries’s treatment strategies stand out for their unwavering emphasis of love for her patients, characterized most notably by her thoughtful policies and sacrifices of time and money. Financial support for the practice was slim to none, especially in the first few years of the epidemic. It was too political to receive much government funding, and patients’ insurance coverage was complicated and often unaccommodating – some insurance companies deliberately avoided working with Ries’ practice after learning it was for HIV/AIDS patients. Dealing with the lack of financial resources along with the process of bringing in medications and other resources required hours of paperwork. Ries, with a feeling that it’s just what she had to do, stayed after hours most nights to complete it. Furthermore, a lot of the money that they did receive went into a bank account she started for the patients and was used to purchase medications, pay co-pays, and generally support patients without money. When Snyder joined the team, they spent time making home visits to patients on the weekends and visiting schools and other groups to educate about HIV.

“If worst comes to worst, we figured out a way to pay for it. We did not let anybody go without medications, however we could do it.”

- Christine Jamjian, pharmacist at Holy Cross

Additionally, their practice was built around making physical contact with their patients. During the height of the epidemic and as the stigma around it intensified, there was a universal fear of touching people with HIV. Especially before knowledge of how the disease was transmitted was well-known, HIV patients were seen as disgusting. Ries quickly realized the impact this stigma had on her patients and wanted to make sure they didn’t believe it. Under Ries’ instruction, everyone working with the HIV/AIDS patients prioritized skin-to-skin contact by way of holding hands, touching shoulders, and ending every visit with a hug. These policies in tandem with their authentic, accepting conversation rhetoric proved that their patients’ best interest was truly the heart of their efforts even if their resources were exhausted.

Building Community

Ries and Snyder’s practice fostered unity among providers, most of whom were also women in medicine. Holy Cross Hospital stood as the only medical center in Utah willing to accept HIV/AIDS patients at the height of the epidemic, making their practice both a refuge and a focal point for the community’s response. The overwhelming demand on their services required them to build a close-knit team that thrived on mutual support and shared purpose. For many providers, this work offered more than a professional connection. Christine Jamjian, a pharmacist from Lebanon who had recently moved to Utah, described how this environment helped her feel at home in a new place, “I mean, it was such a great environment. It just felt like family. And I think this was why I liked that clinic so much. It was a family that I didn’t have here. You could say whatever you want. You could act however you wanted.”

This sense of belonging extended across the entire team, creating a cohesive and collaborative environment that was vital to their mission. Linda Bellemore, a nurse at Holy Cross, reflected on how this unity allowed them to face the crisis together, “Caring for these folks as a member of the team of Holy Cross Hospital was also a privilege and a blessing. It accrued an album of wonderful memories because it was not only me usually, it was other people. We did this all together.” In a time when fear and stigma surrounded HIV/AIDS, this communal spirit among providers was essential. It gave them the strength to continue their work and to provide patients with a sanctuary of hope and care, even as the epidemic raged around them.

References

Blarsen, Andy. “How the Latter-Day Saint Population Has Changed over Time in Utah’s Counties.” The Salt Lake Tribune, 10 Dec. 2022, www.sltrib.com/religion/2022/12/10/how-latter-day-saint-population/.

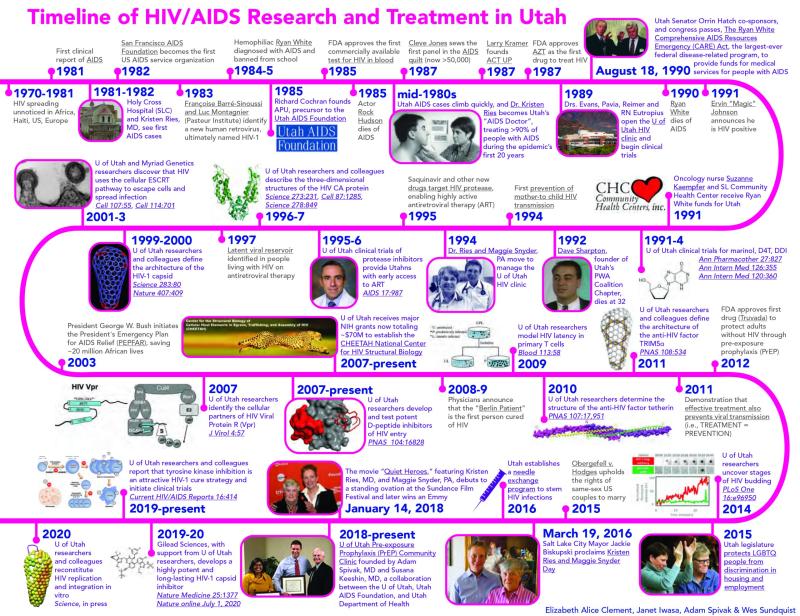

Clement, Elizabeth. “Timeline of HIV/AIDS Research and Treatment in Utah - @theu.” theU, attheu.utah.edu/facultystaff/timeline-of-hiv-aids-research-and-treatment-in-utah/. Accessed 6 Dec. 2024.

HIV oral history project, ACCN 2958, Box 1, Folder 3. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah.

Later edited by: Pamalatera C. Fenn

HIV oral history project, ACCN 2958, Box 1, Folder 7.. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah.

HIV oral history project, ACCN 2958, Box 3, Folder 4. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, The University of Utah.

Note: Quotes were adapted from interviews conducted by Elizabeth Clement as apart of an HIV Oral History Project located in the University of Utah Archives