Western Influence on Women and Medical Practices: Chinese Hospitals (19th Century to 20th Century)

The following report is based on readings found in the online archives from the, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library University of Utah titled, "The Susan Barbara Tallmon Sargent Papers". Which show a window to the past in China during the 1900's specifically focused around her time there as a medical missionary. There are also outside academic sources cited at the bottom of the page.

Medical Situation in China 1900's

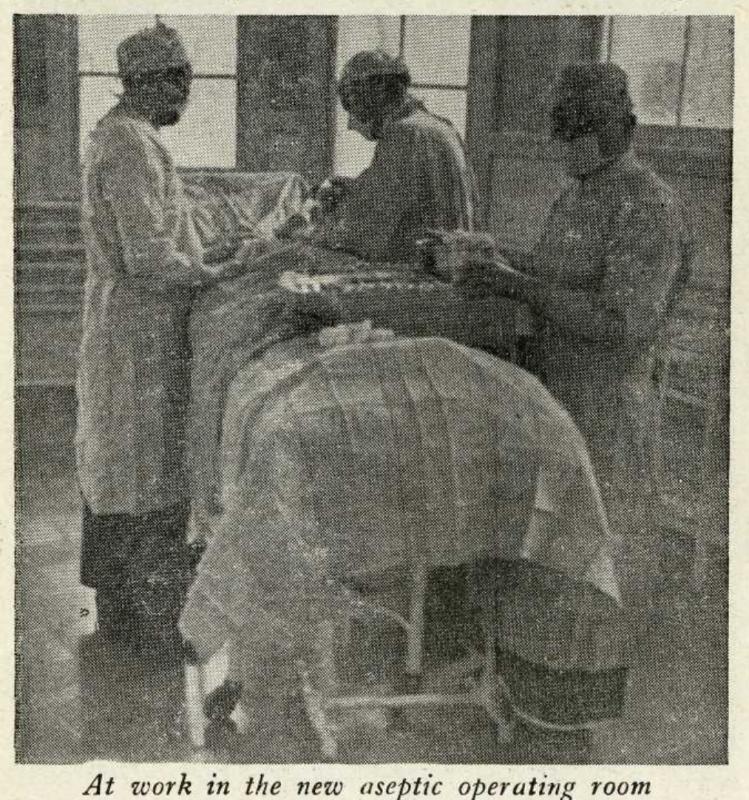

To better understand the medical situation in China in the 1900's we need to look back at what it was like before that. It is explained in an article that, "Up until the 19th century, there was no Chinese medicine; there was “medicine” (yi), a term that encompassed all forms of medicine and healing as well as those engaged in such activities, be they an imperial physician (tai yi), an itinerant peddler of medicines (ling yi), a quack (yong yi), or a Confucian physician (ru yi)." (Fu, 2022) The advances in transportation in the 1900's in the West had made it easier for Westerners to visit other countries, such as China. Due to the influx of Western information, religion, and medicinal practices the idea of "yi" needed to adapt to the changing world as well. "The concept of Chinese medicine did not exist until Chinese physicians found themselves forced to define their field in order to distinguish it from the medicine of the West." (Fu, 2022) The birth of, "Chinese medicine (zhongyi) is better understood as a marker for an assemblage of theories, technologies, and practices that defy simple definition. Interactions with Western colonialism, scientific ideas, and new biomedical technologies shifted the organization and composition of existing theories, technologies, and practices—sometimes minimally, sometimes in quite unexpected and profound ways."(Fu, 2022 ) Through the Influence of Western colonialism through medical and religious missionaries with their new ideas, resources, and religious idols, many countries had to adapt whether they wanted to or not. "Western medicine (xiyi), for similar reasons, traversed a similar pattern. Since the 19th century, Western medicine has been used inconsistently to refer to Chinese physicians who had studied abroad, foreign medical missionaries residing in China, as well as an approach to medicine and healing based in biochemistry, anatomy, and physiology." (Fu, 2022) Therefore the 1900's medical situation could be boiled down to "evolving" as more Western influence was coming in the house that was chinese "yi" was being torn down from a straw hut, to a house with the resources that were bought in by westerners. At first people were hesitant to accept this evolved form of chinese medicine as well as western medicine itself. This tension could be traced back to the contention leftover from the Boxer Rebellion that went from 1899 -1901, and was caused by anger towards the influx of christian missionaries. Leading to hate crimes against christian missionaries and thus the start of the rebellion. Through the means of western findings aspeptic surgical rooms were able to be created to help those cases which were sadly turned away from the clinics as they did not have a means to assist the patient.

Dr. Susan Barbara Tallmont Sargent

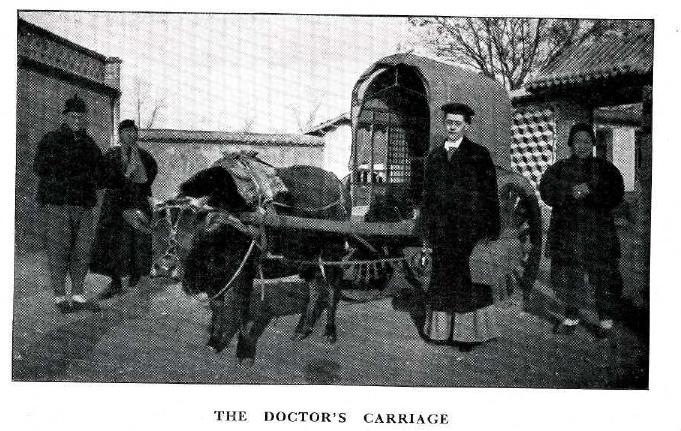

One of these medical missionaries in China at the time (after the Boxer Rebellion) was, Dr. Susan Barbara Tallmon Sargent (You can read more about her personal life by clicking on her name) a dedicated woman physician, who is mentioned throughout many hospital related documents at the time. Many documents have been preserved and are attributed to her name and can be found as, "The Susan Barbara Tallmon Sargent Papers" on the J. Willard Marriott Digital Library University of Utah. From one of these pamphlets it states, "Dr. Susan B. Tallmon came to China in December, 1905, and in February, 1908, opened a dispensary on Bamboo Street with an appropriation of one hundred and twenty-five dollars from the Woman's Board of the Interior." (Pagoda Pamphlet No.1, pg. 4)

Before the hospital was built, Dr. Sargent was provided funds to build the dispensary which was a 16 feet square room that served as a private examining room and a drug room as well. From there they needed to then attract people to come to them when they were sick or had any other ailments so, "At first no charges of any sort were made, some of the helpers urging that this would be the better way, leaving it to the patients to make such gifts as they chose. This plan brought goodly sized clinics each day,--but nothing for the cause of self-support." (Pagoda Pamphlet No.1, pg 5) Most of the patients that came were children with a variety of ailments most of them were simply malnourished, or had ringworm on the scalp (a common fungal affliction). From reading the Pagoda Pamphlelt No.1 it is clear to see that Dr. Sargents reputation with the children helped people be more open to coming to recieve treatments from the dispensary. As they recalled overhearing a child state, "Why don't you go to Dr. Tallmon ? You know she gives good medicine!" (Pagoda Pamphlet No.1, pg.7) As well as recounting an endearing story of the special connection she had with the first Chinese baby she delivered, "...(lien Ch'un by name) was the first

Chinese baby whom Dr. Tallmon welcomed into the world. He is not yet two years old and can not master the intricacies of the two syllables of the Chinese word for doctor, so he calls her what would be an equivalent to "Doc." He is very proud of a pair of new shoes he has just acquired, and wants to put them on every time he sees them. Once when he was making his wishes known along this line, his mother said, "What do you want to put them on for?" "Doc see," was the quick response." (Pagoda Pamphlet No.1, pg7). Through these crucial encounters, they were able to build a trusting relationship with the community, that would later be key to establishing a successful thriving hospital.

Western Medicine and Chinese "Yi"

1910 was a time where Western influence in Chinese medicine was just beginning, there was no intricate surgeries performed yet, and the ways to treat sickness were heavily based on regional culture and traditions. As a letter from Dr. Sargent recalls an experience where this clash between western medicine and "Yi" was very apparent. "Perhaps you remember hearing about the children with spleenic enlargement for whom we prepared milk and eggs and bread daily for a time last year. The little Mohammedan boy whose mother could not be persuaded that his illness was really serious was brought to the hospital a few days ago in much worse condition than last year. He had complained of pain in his abdomen so his mother had bound on a "fish." The "fish" proved to be a turtle some eight inches across. Its head and feet had been cut off and the skin sewed up so that it "could not bite or scratch." He had worn it already for several days but without great benefit. His mother was urged to bring the boy to the hospital as nothing but constant treatment can do him any good." (Pagoda Pamphlet No.1 pg. 8)

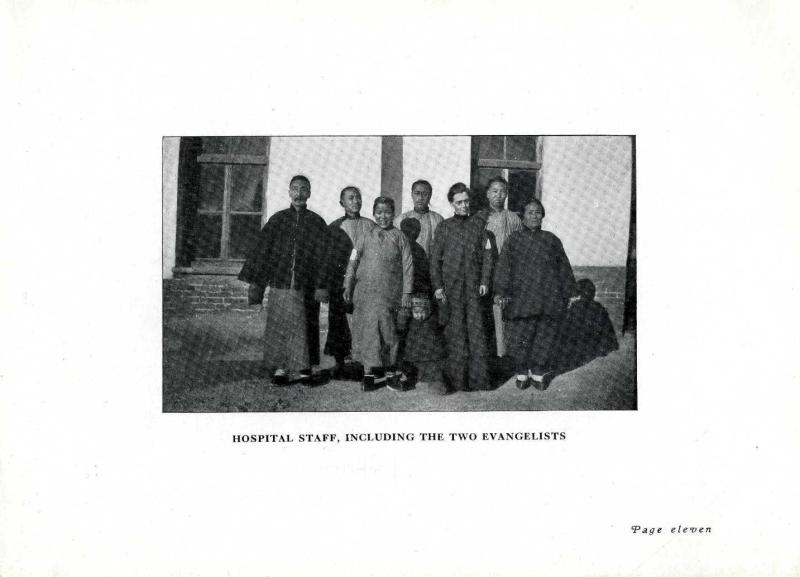

For a time they simply worked out of the dispensary, then a un-named sponsor from the states donated 1,000 dollars to helping build a hospital in Lintsingchow. From there they were able to build, "Four rooms for women patients, one for children...two for men, an operating and dispensing room, places for the Bible woman and teachers and gateman to live, an office and a waiting room..."(Pagoda Pamphlet No.1 pg 10)

Because of the reputation that had been developed because of the dispensary and Dr. Sargent, the new compound was able to be immediatley put to use as soon as it was opened. "Patients began to come as soon as it was opened, in fact some had been waiting for it to open, and it has been used almost to its full capacity during these three months." (Pagoda Pamphlet No.1 pg.10). Through the successful treatment of patients, grateful patients would show a unique way to thank their doctors and medical staff, "To spread one's fame, is the special way in which a Chinese delights to show his gratitude for a favor received. "If you will only cure me, I will tell about your skill everywhere I go," . . ."I will certainly spread your fame in my native village when I return home," says the joyful

woman. . . We had just begun to realize that grateful patients leaving our gates meant an increasing number who would be coming to us..." (Pagoda Pamphlet No.1 pg 10) A few months later through the acceptance and success of the hospital , the Womans Board of the Pacific approved the building of a Women's Hospital!

Western Influence on Chinese Women

Looking back a little during the Boxer Rebellion (1899-1901), villages would decide what part they would take in the rebellion independently (sometimes collaborating). However, the action of the women in these villages was always the same, while the men would go off to fight they would rally together and figure out how to help. They organized themselves into groups the more notable one being Red Lanterns, "The Red Lanterns were an organization of young women between the ages of 12 and 18. Ocassionally they even included girls as young as 8 or 9. . .These young women neither arranged their hair in the traditional manner nor bound their feet". (Ono, 1989, pg 49) The rebellion was a time of liberation for many women, where women such as the Red Lanterns learned to weild swords and fans and found a community with other women. After the rebellion things were expected to go back to the way they were, including the expectations they had for women at the time. Receiving an education not only was it hard for women to recieve an education inside of China, there was not much action taken to help this situation; Women needed to travel to Japan to achieve their dreams of receiving an education, which meant only women from well off families could recieve an education. Any progress to have education taught directly in China would end up faltering and not coming to fruition, "Arguing for the necesssity of women's public education to the conservative Qing authorities was Hattori Unokichi, professor at Daxuetang. . . He had recommended Shimoda to the Empress Dowager and sought to have the education of Chinese women entrusted to her. . .the Empress Dowager began confidential negotiations. . .However, with the death of the Empress Dowager in 1908, her promise to Hattori came to naught. . . "(Ono, 1989, pg 56)

As missionaries form the West kept coming into China they would build boarding school for girls where they taught basic things such as reading and sometimes writing (when they had the means) but mostly they taught christian religious beliefs. At the hospitals western staff came to realize quickly the attitude towards delivering baby boys vs. baby girls and what that meant for their reputation as well.

The attitude towards women and girls in China at the time was very negative because of the patriarchal social structure. In the hospitals mentioned in the pamphlets this attitude is very obvious, "We had only sixty-six deliveries, but even if these are not many, we think ourselves lucky for we had 100% more boys than girls! It would lead us too far to tell how badly Chinese families want boys and how unhappy they usually are when they get a girl. Had we had more girls, our reputation would be gone" (Williams Porter Hospital, Tehchow, Shantung, China, Annual report 1939, pg 19) As westerners presence became more regular they were able to see the change in treatment of women becoming more inclusive (though still full of inequalities) there was new change. And chinese women began to adopt the idea of becoming educated beyond common housekeeping. Though the challenges they faced were many, they were able to join together to change tradition becoming a fusion of western and chinese ideologies. Though they face the same obstacles all women face globally, chinese women face greater setbacks due to the strict patriarchal chinese culture. While women may still face challenges in today's world, seeing how things have changed over the last century gives us an optimistic outlook towards the future.

Works Cited

- Fu, Jia-Chen. "Health and Medicine in Modern China." Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History. April 20, 2022. Oxford University Press. Date of access 2 Dec. 2024, <https://oxfordre.com/asianhistory/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-137>

-

"Pagoda Pamphlet No.1", Accn110, bx 1, fd 8. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, The University of Utah.

-

"Williams Porter Hospital, Tehchow, Shantung, China, Annual report 1939", Accn1107, bx 6, fd 2. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, The University of Utah.

-

Ono, K. (1989). Chinese Women in a Century of Revolution, 1850-1950. Stanford University Press. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=o-L1ctqjxNgC&oi=fnd&pg=PR5&dq=treatment+of+women+in+China+during+the+1900%27s+&ots=UWee-hBXse&sig=0AaJMvGIeUy7jxk_dpPO-TycRVE#v=onepage&q&f=false

-

"Annual report of the North China Mission of the American Board for the year May 1st, 1912 to April 30th, 1913", Accn1107, bx 6, fd 1. Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Digital Library, The University of Utah.

Report Written by: Liliana Robledo

Edited by: Derek Coombs

Later Edited by Pamalatera C. Fenn