Introduction

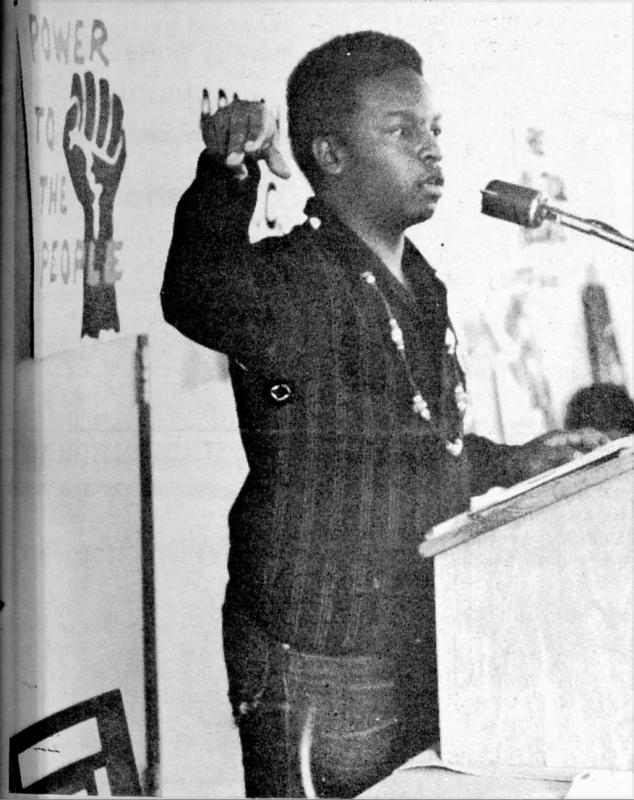

In the late 1960s and early 70s, African American college students protested. They wanted more Black students and teachers, Black history classes, and less discrimination. Students held sit-ins, wrote demands, and hosted events.[1] Black students, faculty, and staff at the University of Utah joined. They formed the Institute for the Study of Black Life and Culture to provide classes and resources for Black students. [2]

Utah in the 70s

Racism ran rampant in 1970s Utah. Few Black people lived in Utah, and they faced severe racism. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints did not give Black people the priesthood from 1852-1978.[3] This meant the Church did not allow Black men to have leadership positions. Racism in the Church often meant members engaged in racism outside of church, negatively impacting Black Utahans lives.[4]

Within this social climate, it is unsurprising that few Black people called Utah home. The 1970 census reported 6,617 Black people within the state.[5] In other words, Black people made up about 0.6% of Utah’s population. Black student representation at the U matched the state with Black students made up only 0.6% of the University of Utah’s student body in 1971.[6] In the same year, the U employed 10 Black faculty. Most of these faculty held “instructor” roles and did not have the protections associated with tenure.[7] The number of Black staff in the 70s is unclear. Despite minimal Black representation on campus and the lack of career protections, Black faculty, staff, and students at the U found ways to improve conditions for themselves and future community members.

Purpose and Notes about the Exhibit

This digital exhibit aims to portray some of the ways that some Black faculty and staff at the University of Utah engaged with the broader movement in higher education to challenge institutionalized racism. It is far from the complete story. Rather, this exhibit hopes to start conversations serve as a starting or inspirational point for future research by both the author and other scholars. In so much, this digital exhibit aims to walk a fine line between narrating the story and digitizing documents for the public to make their own judgements.

Since this project aims to share documents from the archives with the public, there are not footnotes for quotes or information included in documents on the same page. Finally, this is part of an interactive project. Much of the same information has been published by the author as an ipresentation. It can be found at this link.

This project also deals with relatively recent history. The documents and stories shared are included after weighing the copyright and privacy concerns and including shareholders and copyright owners whenever possible. However, if a copyright holder feels their documents or stories should not be shared, they are encouraged to contact the Marriott Library and request the information be taken down.

[1] For information on Black college student protest in the late 60s and early 70s see Ibram X. Kendi, The Black Campus Movement: Black Students and the Racial Reconstitution of Higher Education, 1965-1972 (New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan US, 2012), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/utah/detail.action?docID=931759; Stefan Bradley, Upending the Ivory Tower : Civil Rights, Black Power, and the Ivy League (New York City, NY: New York University Press, 2018). Brandon James Render, “‘WE WANT A QUOTA!’ Black Student Enrollment at the University of Texas at Austin, 1969–78,” Journal of Human and Civil Rights 8, no. 1 (2022).

[2] Michael Clark to Carlos Esqueda, January 7, 1970. University of Utah Ethnic Studies Program records, Acc. 503, Box 1. University Archives and Records Management. University of Utah, J. Willard Marriott. Salt Lake City, Utah

[3] Joanna Brooks, Mormonism and White Supremacy: American Religion and The Problem of Racial Innocence (Oxford University Press, 2020), https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190081768.001.0001. 11.

[4] For examples of Black Utahan’s experiences, see Colleen Whitley, Feed My Sheep: The Life of Alberta Henry (Chicago, IL: University of Utah Press, 2019); Victor Gordon, Interviews with African Americans in Utah, Victor Gordon, Interview 2, June 16, 1984, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=893691; Victor Gordon, Interviews with African Americans in Utah, Victor Gordon, Interview 1, March 27, 1984, https://collections.lib.utah.edu/details?id=893624.

[5] U.S. Department of Commerce, “General Population Characteristics: 1970,” Utah: General Population Characteristics, accessed February 21, 2024, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1971/dec/pc-v2.html

[6] Franklin McKean to R. J. Snow, June 27, 1975, University of Utah Student Affairs Office records, Acc. 354, Box 4. University Archives and Records Management.

[7] “Minority Faculty Members,” 6/22/1971, University of Utah Student Affairs Office records, Acc. 233, Box 12. University Archives and Records Management. University of Utah, J. Willard Marriott. Salt Lake City, Utah