Howell, Abner Leonard

Biography

Abner Leonard Howell was the eldest child and only son born to his formerly enslaved parents, Paul Cephas and Mary Elizabeth (Eliza) Sharp Howell. As a twelve-year-old child, Abner moved with his siblings and mother to Utah to reunite with his father who had moved ahead of the family in search of work. Abner thus spent his formative teenage years in association with white Latter-day Saints and after attending worship services with them for more than twenty years he accepted baptism at age 42 and remained a committed Latter-day Saint for the rest of his life. He and his second wife served an unofficial mission for the faith and Abner immersed himself in civic and religious service. He associated with the highest levels of Latter-day Saint leadership and was designated an honorary high priest, although never officially ordained to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ lay priesthood. In many respects, his life represents the leadership capacity that his chosen faith lost in the wake of its racial teachings and policies.

Abner was born on August 9, 1878 in Mansfield, DeSoto Parish, Louisiana. After they were emancipated, Abner’s parents, Paul and Mary Eliza, along with Paul’s brother, Levi and his family made plans to leave Louisiana and go West where they hoped to find more opportunities for advancement. The Howell brothers gradually moved their families westward, stopping briefly in various cities to work and accrue more money to finance their travel. By the late 1880s, Paul had gone ahead to Salt Lake City, leaving his wife and children in Denver with Levi’s family. A building boom in Salt Lake provided plenty of work for skilled laborers, so the Howells found what they were looking for in the city. Later in life Abner suggested that his father had encountered Latter-day Saint missionary and future leader Wilford Woodruff in Arkansas while enslaved and that Woodruff had told his father to come to Utah once freed but no evidence has been found to corroborate that story, especially given the fact that the Mormons had not yet settled in Salt Lake City in 1835 when Woodruff preached in Arkansas.[1]

Upon his arrival in the valley, Paul Howell found employment as a bricklayer and hod-carrier. By 1890 he was able to send for Eliza and their children, six in all. In addition to Abner, the Howells had five young daughters, four of whom were born on the road to Utah Territory. When Eliza and the Howell children got to Salt Lake, Eliza rented a hotel room and began to look for Paul, describing her six-foot-two-inch-husband to residents. Family tradition says that on their second day of searching, Abner spotted his father working on a building project and called out, “Papa, Papa!” The Howell family, finally reunited, stayed in Salt Lake, making the growing city their permanent home.[2]

Paul Howell had prepared for his family’s arrival by finding a four-room house located downtown. He had crafted several pieces of furniture to make it comfortable for Eliza and their children. It was in this home in Mortenson Court (228 East 500 South) where Abner Howell first became acquainted with children who were members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.[3] The Steinbach family, who lived nearby, belonged to the Church. One of the Steinbach’s sons was about the same age as Abner and took him to Sunday School several times. When the Howells moved a few blocks away to Third South Street, Abner developed ties to a second Latter-day Saint family who lived nearby, the H.T. Covey family who raised sheep. Theed Covey became a close friend of Abner’s and invited Abner to help move the sheep to grazing pastures in Wyoming. They made the trek to Cokeville in covered wagons when Abner was a teenager.[4]

By 1900, a third relocation brought the Howell family next door to the Lucy and Hyrum Smith Young family. Hyrum Young, a banker, was also a well-connected Latter-day Saint, being one of Brigham Young’s sons. Hyrum Young hired Abner to do chores for him. Although Abner worked as a delivery boy at a nearby meat market, he found time to clean Young’s stables and milk his cows for $1.00 a week. Abner’s sisters also grew close to the Young family. When Lucy Young treated her children to Sunday afternoon carriage rides, she often included the Howell girls.[5]

Abner’s mother was a committed Methodist and when the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) church was organized in Salt Lake, the Howells attended activities with their mother’s co-religionists, but that was not the only place they received religious instruction. Abner’s sister, Byrdie Howell Langon explained that in the early days of Salt Lake, “no churches were owned by the black people.” Even after the A. M. E. Methodist church was organized, there were so few members that the bishop could not appoint a minister, so, “Sometimes we would have a white minister. . . or an evangelist passing through. . .if we did not have a minister, the laymen would read the scripture and congretation[sic] would sing songs and pray and tell testimonies.” In any case, “Sunday was a Holy day” for the Howell family and their “children went to Sunday school practically all day. At 10:00 we would go to the Mormon Sunday School,” Langon recalled, “and later on to the white Baptist Church, and then to the Methodist in the afternoon.”[6]

Although children were expected to refrain from playing sports on Sunday, Abner related a youthful experience in which some of his friends intended to sneak in a Sunday game of baseball. Unfortunately, the only boy in the neighborhood who owned a baseball mitt was the Mormon bishop’s son. Suddenly Abner’s friend yelled, “Jiggers, jiggers, hide the mitt!” There was a scramble to stash the evidence before the bishop caught on.[7]

Unlike his parents, Abner had the opportunity to attend school in Salt Lake City and become literate. When he recalled some interactions he had with his fellow students and the friends he made, he told about a time in third grade when his teacher asked her class to memorize a poem. There were no books in Abner’s home, but Ada Bitner, (the future mother of Latter-day Saint leader Gordon B. Hinkley) offered to find “a piece” for him to recite. He remembered it all his life and patterned his life on it: “Try and try again boys, you’ll succeed at last.”[8]

It was only when Abner looked in the mirror that he remembered he was Black because he felt so well accepted and integrated in his school days. When his friends had house parties, several of the unaccompanied girls who lived in his neighborhood told him, “My mother said I should walk home with you . . . I considered that an honor,” Abner later recalled.[9]

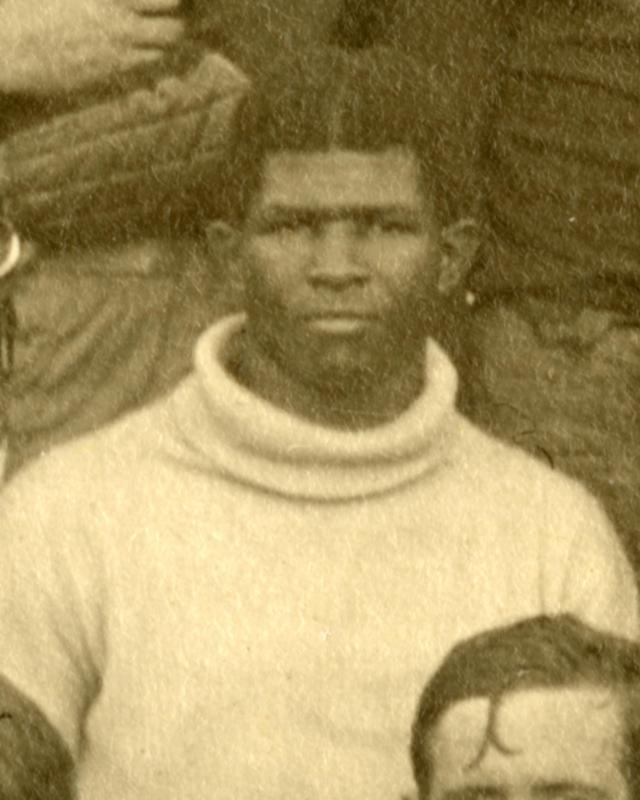

As Abner entered his high school years, he proved to be an extraordinarily gifted athlete. He strove for excellence in many sports but he earned widespread notoriety in football. He attended the only high school in the city, Salt Lake High. He played football there under Coach David Callahan. Abner was a fullback on a team remembered for its exceptional athleticism and ability.[10] Abner’s sister claimed he was “as famous in those days as Willie Mays” was in the 1960s.[11] In their most celebrated game, attended by over 5,000 people on Thanksgiving Day in 1900, the Salt Lake High boys shut out the East Denver High team 34-0. The Deseret News reported, “When it came to individual plays Abe Howells [sic] took the laurel leaf. He was everything from the bandwagon to the steam calliope.”[12]

Although his athleticism earned Abner acclaim, as the only Black member of his team, his race also set him apart. The Deseret News’ sports reporter, for example, heaped praise on Abner for his athletic prowess, yet repeatedly called attention to his race. One report described Abner as the “dusky cyclone” or simply the “colored boy.”[13] The Salt Lake Tribune similarly referred to Abner as the “colored wizard”[14] while a later article, published in 1933 in the Salt Lake Telegram, named Abner “the black streak.”[15]

It was not merely the newspapers who made racial distinctions, however. After Salt Lake High’s solid victory against Denver, the gridiron stars went out to a restaurant to celebrate. The restaurant staff intended to consign Abner to the kitchen, but team solidarity and respect for Abner’s talent overcame the restaurateur’s reluctance to serve him with the White patrons. Nicholas Groesbeck Smith, Abner’s teammate and former neighbor, spoke up for the team and told the staff that it would be fine to serve Abner in the kitchen, but if they did, all the boys would eat in the kitchen with him. The restaurant staff relented and the entire team ate dinner together in the dining room.[16]

Abner enjoyed a close friendship with Nicholas Smith that lasted until Smith’s death in 1945. Abner spent time in Smith’s home and he and his father, John Henry Smith, proved to be influential in Abner’s spiritual life. Speaking to a Latter-day Saint audience over fifty years after the famous Thanksgiving game victory, Abner told how Nicholas took him below the bleachers before the game started and ordered him on his knees in prayer. Abner admitted that he did not know much about how to pray at the time, but Nick “offered up a wonderful prayer.”[17]

In that same talk, Abner commented on how much football had changed in the intervening years. He lamented the fact that the forward pass had not been a part of the game he played. He told the group that in 1894, he and Nicholas Smith attended the final game David O. McKay (future president of the LDS Church) played at the University of Utah. After the game, Abner had a meaningful experience when he and Smith were able to meet McKay, a young man they both greatly admired as a person and as an athlete.They told McKay, “How we wish we could play like you!” Hearing that, McKay put his arms on their shoulders and told them, “You will someday be greater than I am. You’ll play greater ball.” Their high school team did, in fact, play more teams than McKay’s team had and even beat the University of Utah.[18]

Abner’s talents extended beyond the football field to other areas of his life. While still in high school, Abner submitted to a competition to win a place at West Point Military Academy. In 1897, the elite school offered a cadetship to the most qualified applicant found in Utah. Abner was one of “eight ambitious young men” who underwent a physical and a written examination at the University of Utah to try to win the position.[19] Abner made it to the last round, but Charles Telford was “the Lucky Man” who scored the highest marks on the “very rigid” exam and was able to pass the tough physical test. However, all the finalists, including Abner, were deemed “a bright lot of fellows” and the results were “very close.”[20]

Abner’s high school years ended in the spring of 1900. He claimed the distinction of being the first Black student to graduate high school in Utah. The seniors organized a variety show to celebrate their graduation. Abner’s contribution was “one of the best numbers of the evening, a little ragtime solo about the freshmen that received a hearty encore.”[21] Evidently, Abner was musically talented, as well as athletically gifted.

The Howell family availed themselves of social and professional opportunities open to them in Salt Lake. Abner’s father, Paul, became the city’s second Black police officer in 1892. By 1908, he rose to the rank of detective, becoming the first Black detective on the force. He was a prominent member of the Black community, involved in racial causes.[22] His children followed suit. Abner’s achievements and ambitions were clearly not confined to the field of sports. He, his sisters and his cousins were active in the Black social world that flowered in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the city. Numerous local newspaper articles recount the Howell family’s participation in events sponsored by various fraternal and social organizations.

In the summer of 1900, the Western Negro Press Association met in Salt Lake City. Being committed to the elevation of his race in society, Abner attended the conference and took part in the proceedings. He presented condolences on the death of members of the Press Association. Heber Wells, the governor of Utah at that time, addressed the association and complemented them on engaging “in the noble work of uplifting their fellow-men.” He went on to say, “the negro in this country has had to fight his way into public recognition inch by inch, and the fact that he has succeeded so well is evidence of the superior force, ability and courage within him.”[23]

Abner was actively involved in other social organizations as well. The Grand United Order of Odd Fellows was a fraternal order that organized Black lodges, including in Utah. Abner was a member and his sister, Annie, joined the women’s auxiliary, the Household of Ruth. On May 12, 1901, the Black Odd Fellows lodge organized a Thanksgiving service at which Abner was master of ceremonies. A street parade led by a local band preceded the two and a half hour evening service. The Odd Fellows marched behind the band and the members of the Household of Ruth followed in horse-drawn carriages. Both Black and White Salt Lake residents attended the Thanksgiving service. It concluded with a speech given by Abner dressed in Odd Fellow regalia.[24]

Around this time, Abner, evidently even tried his hand at a business venture. The 1901 Salt Lake City directory listed a retail cigar store on Commercial Street under Abner’s name.[25] He may not have met with much success because it only appeared in the directory that one year.

When offered a chance to see a part of the country he had never seen, Abner enthusiastically agreed to a stint as a railroad porter. In 1902, Heber J. Grant, then a Latter-day Saint apostle, asked Abner to serve as a Pullman porter for him and fifty missionaries headed to the missionary field in Japan by way of Oregon. Abner liked the church leader because he had allowed Abner to play baseball on his local amateur team. Abner thus agreed to Grant’s request, saying, “Sure. I’ve never been north of Ogden yet, so that’ll be fine with me.” Telling a church group about this experience many years later, Abner relayed Grant’s response when the missionaries pleaded with Abner to continue on to Japan with them. The apostle told the missionaries that it was impossible because Abner had to go back to Salt Lake with the Pullman Car. He then promised Abner, “As long as you stay faithful to your church and endure to the end, you will always have good luck. Fortune will always smile upon you, mentally, physically, and spiritually.”[26]

After returning from Oregon, Abner headed east to Michigan to study law. Some of his high school classmates had chosen to attend the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor and Abner also hoped to graduate from the prestigious school. He applied and was accepted, but his family lacked the money to pay for his tuition. It took him two years, working at several jobs, to earn the necessary funds.[27] Abner began his legal studies in 1902. He was listed as a second year student in Michigan’s Department of Law in the 1903-1904 school calendar.[28] Not only did he study law, he earned a place on the Wolverine’s All-Freshman football team. The Michigan yearbook included a picture of Abner with the Varsity Reserve team as well.[29] Abner’s studies at the university coincided with the earliest years that Fielding Yost coached the undefeated varsity football team and Abner seems to have been on track to play on the celebrated team.

It was in Michigan that Abner met the woman who would become his wife. On August 30, 1904, Abner married Nina Viola Stevenson in Detroit.[30] She was Michigan-born and raised. After his marriage and the birth of the couple’s first son, Jay Marshall Howell later that year, Abner’s financial obligations mounted. He simply could not afford to continue law school as well as support his family. Nevertheless, Abner, Nina, and their baby stayed in Michigan for a few more years while Abner worked as a brick layer. The couple welcomed a second child, daughter Gay June (Abbie) Howell on November 14, 1905. City directories for Detroit, Michigan list the Howell family there until 1909.[31]

By 1910, Abner had returned to Salt Lake City with his family in tow. Abner and Nina’s third child, Lucille Mary Howell, was born in Utah on November 2, 1910. After returning to Salt Lake, Abner continued to work as a brick mason.[32]

Over the next twelve years, the Howells added three more sons and two daughters to the family: Paul, born in 1912; Edna Viola, born in 1915; Floyd Leonard, born in 1917; Glen Robert in 1920, and Mary Juanita came into the family in 1922.

When the Howells returned to Salt Lake, they first lived in the northern most part of the city within the boundaries of the Salt Lake LDS 23rd Ward.[33] Locals called the neighborhood “Swedetown” because of the concentration of Swedish Mormon converts who lived there.The Howells were among a small handful of people of color living among their predominantly Scandinavian and English neighbors. Even still, it was in this location that Nina and Abner’s eldest son, Jay, and eldest daughter, Abbie, were baptized and confirmed members of the Church in 1915.[34] The children were the first of the Howell family to join the faith. It would be six more years before their father and mother received baptism.

By the summer of 1920 when the census taker passed through, the Abner Howell family had moved from the north end of Salt Lake City to the neighborhood of Holladay further south below the foothills of the Wasatch mountains. Holladay was a rural area and according to family knowledge, Abner and his family had a small farm on their property where they kept a herd of sheep.[35] The Howells were the only Black family counted among the 2,600 residents of their census precinct that year. Abner listed his occupation as a bricklayer at the American Smelting and Refining Company in Murray, Utah, directly west of the Howell home.[36]

Abner and Nina’s young son, Paul Cecil, died of kidney failure on February 17, 1921.[37] Only nine days later, on February 26, 1921, Abner, Nina, and their ten year-old daughter, Lucille Mary, were baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. They were confirmed on March 6, 1921 in the Holladay First Ward.[38]

Abner had been moving closer to becoming a Mormon for a very long time. He later said that he had attended the LDS church for twenty years before he finally joined. In 1965, he recounted his conversion story this way:

Before I was in my teens I wondered many times why I was a different color to the other boys. Little by little I was told that I was cursed and could not go to heaven when I died, but was doomed to go to hell with the devil and burn forever.

One day, when the boys were telling me these things, I was so touched that I began to cry. While in this frame of mind, Bro. John Henry Smith [LDS apostle and father of Abner’s schoolmate, Nicholas Groesbeck Smith] came along and wanted to know what was wrong . . . so I told him. He comforted me with a few kind words and took me to his house . . . he got out the Book of Mormon and turned to the 26th chapter of 2nd Nephi, and the last verse. He then said "read this," which I did. When I was through reading, a great load was lifted from my heart and mind, and my eyes were opened, and I read more and more. I thought how great that was! The words “all are alike unto God.”

I could not find anything in the Bible that pleased me as much as what I had just read in the Book of Mormon. I never discussed my thoughts with anyone. I just dreamed day after day to myself. I did not tell my mother about this as she did not want [me] to join the Church . . . With this background I grew up joining no church but with all Latter-day Saint ideas, ways and thoughts.[39]

In another context, Abner was more specific about the boy who told him he could not go to Heaven. Speaking to fellow Mormons, late in his life, he told his audience that he had a “hard time coming up” because he was the only Black boy of his age in the area. Non-Mormons, at that time, were called “Gentiles” and it was one of the “Gentile” boys who questioned him, “Don’t you know that black boys don’t go to Heaven?” Abner remembered the boy bluntly telling him, “All black people go to Hell.” When Abner told John Henry Smith what the boy had said, Smith told Abner, “ Don’t believe that.” [40]

Abner spent thirty years living among members of the LDS Church, associating with Mormon leaders and even attending worship services, believing, but unbaptized. After he and Nina joined the Church, Abner remained a committed Latter-day Saint, actively participating in church life to the extent he was permitted and contributing to the building of what he regarded as God’s Kingdom. However, he did not cease to struggle with the troubling question of why his race could not hold the priesthood.

Abner and his family continued to live in Holladay as they raised their children and Abner worked as a bricklayer and laborer. When each of their younger children reached the age of eight, Abner and Nina made sure he or she received baptism and confirmation as a member of the LDS Church. Paul, their second son, had not been baptized before his death at the age of nine. Abner requested a posthumous baptism and confirmation for Paul. Those proxy ordinances were performed on Paul’s behalf in the Salt Lake Temple on February 1, 1938.[41]

Not only did the Howells lose a son to an early death, in 1939, their sixteen-year-old daughter, Mary Juanita succumbed to complications of diabetes.[42] She was their youngest child. The other six Howell children lived until adulthood and all of them married and had children of their own.

In 1936 Abner renewed his acquaintance with Heber J. Grant, who by that time had become the president of the LDS Church. Grant had recently organized the Church welfare program. Abner began working for the Church that year and continued until 1939. He helped to build all the buildings at Welfare Square in Salt Lake and demolished the old tithing office. In 1965, he shared a prized letter with a researcher in which President Grant complimented him on his “splendid work” and wished Abner “abundant success in the battle of life.” At the same time, Grant presented him with a book called The Power of Truth. Abner commented that it increased his faith to know that President Grant thought of him as a friend.[43]

President Grant was not the only Church president Abner met. Beginning in his childhood, he spent time in the homes of high-ranking Mormons. He told of meeting Church President Wilford Woodruff at John Taylor’s funeral. Abner thought Woodruff was “just a common man” who would stop at the Howell’s back door to ask his mother, “Mary, have you got any good hot biscuits?”[44] Abner spoke of meeting with other Church presidents and apostles later in his life. He greatly valued his associations with LDS leaders and relating his experiences with them served to secure his place among the mainstream of believers.

Abner’s relationship to the church grew in unexpected ways in the 1940s. His bishop extended an invitation for him to attend priesthood meetings. Because Anber did not hold the priesthood, he had thought this was no place for him, but upon being asked to take part, he did. About two years later, his local leaders asked him to take on the duties of a ward teacher, a calling reserved for priesthood holders. He accepted and became the junior companion to one of the men in his ward who held the office of elder in the church’s higher priesthood.[45]

A few months later, Abner’s companion teacher was unable to make it to an appointment they had made to visit an elderly lady in the ward. Abner’s bishop told him to go by himself. The woman asked him to pray on his arrival, which he did. In response, she told Abner, “How glad I am [that] the priesthood is in my house tonight.” This impressed Abner and he wondered if the Lord had allowed him to act as a priesthood holder without having been formally ordained. Next, the president of his High Priest Quorum invited him to attend their meetings and told him he was an honorary member of the High Priest Quorum of his stake.[46]

After these experiences, Abner visited a boyhood acquaintance, Joseph Fielding Smith, who would later become the president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and asked him what he thought. Smith told him that the Church had bestowed an honor on him and that the priesthood bestowed on Elijah Able came in the same way this honor was bestowed on Abner.[47] It is not clear what Smith meant by this, given the fact that Able was the faith’s first Black priesthood holder, ordained in 1836.

Obviously still struggling with the “baffling question” of why the church did not ordain Black men, Abner turned to a letter former Church president David O. McKay wrote in which McKay admitted that abstract reasoning could not answer the question. He went on to admit that he knew of no scriptural basis for priesthood denial except one verse in the Book of Abraham. McKay asserted that one day Black men would hold the priesthood, but in the meantime, “those of that race who receive the testimony of the restored gospel may have their family ties protected and other blessings made secure for in the justice and mercy of the Lord, they will possess all the blessings to which they are entitled in the eternal plan of salvation.”[48] Abner accepted the teachings of these former church leaders, who, at that time, maintained that the priesthood ban antedated man’s mortal existence and was not a product of simple earthly discrimination. God, being a God of justice, these prior leaders taught, would reward those that performed good works, regardless of their race.

In addition to church participation, newspaper accounts reveal Abner’s involvement in community and racial affairs in the 1940s and 1950s. In 1946, for example, he traveled to Cleveland, Ohio to attend the national convention of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Upon his return, he reported his findings to the local chapter of the association.[49] He was active in labor unions, Community Chest, and the Boy Scouts of America. He was appointed to the Boy Scouts Executive Committee at the beginning of 1952.[50] He was on the welfare board and served two years as the doorkeeper at the Utah Senate.[51] Abner became an associate director of the Utah Association for the United Nations from 1951-1952. The president of the organization that year was Obert C. Tanner, a prominent Utah businessman and philanthropist.[52] The organization was founded in 1948 to “heighten public awareness and increase knowledge of global issues” and “work for peace.”[53]

There were also important events taking place in Abner’s personal life throughout these decades. Early in 1945, Abner’s wife, Nina, died. Losing his wife of over forty years must have been a terrible blow to Abner, but to make matters even worse, the following day, his mother died.[54]

Abner was not alone for very long, however. He remarried that same year, on June 9.[55] His second wife was seventy-year-old Martha Ann Stevens Perkins, the granddaughter of enslaved Latter-day Saint pioneer Green Flake. Martha had been widowed in 1934. Within a few years of the marriage, Abner moved to Martha’s family home in Millcreek, on the east bench overlooking the Salt Lake Valley.[56]

Abner and Martha were devoted Latter-day Saints and in 1951, they received an important assignment from the leaders of their church. Latter-day Saint Presiding Bishop LeGrand Richards signed a letter of introduction which he gave to the Howells as they embarked upon a tour of the southern and eastern parts of the US. The letter was intended to provide an entree for them as ambassadors of the Church as they visited LDS wards. Abner later told a friend that part of the purpose of their excursion was to evaluate the possible success of segregated branches of the LDS Church outside of the Intermountain West. The Howells were charged with the task of assessing the needs of Black members in the South and East.[57]

Abner later wrote about an experience he had before leaving for the South. He reported that when Spencer W. Kimball, then one of the LDS Church’s twelve apostles, heard that the Howells were embarking on this tour, he called Abner into his office to tell him, “You have been raised in Utah and you don’t know those people. You won’t get treated there like you do here. Be very careful, what you say, and where you go. They will always be right and you will be wrong, but say nothing, you will then get along.”[58]

On that informal mission, the Howells, at the request of Latter-day Saint apostle, Mark E. Peterson, visited another Black couple, Len and Mary Hope in Cincinnati, Ohio. The Hopes had been members of the Church for years, but the bigotry of some of their coreligionists in the Cincinnati ward kept them from attending worship services regularly. As Abner later explained, “On arriving in Cincinnati we had a sadder outlook. We found that society had creeped into religion. Most of the members lived across the river on the Kentucky side and some of them did not want the Negro family to come to church. They could only come to church once a month, on fast Sunday.”[59] The Howells attended Sunday school in the branch and Abner was able to answer many questions. After that meeting ended, he gave his introductory letter to the bishop, who then asked him to say a few words in Sacrament meeting that evening. Abner recalled that he prayed for guidance that afternoon and, “that last verse in the 26th chapter of 2nd Nephi said, ‘Read me.’” This was the same scripture John Henry Smith had read to him when he was a child: “He inviteth them all to come unto him . . . and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female. . . all are alike unto God.” At the end of the meeting, Abner said, “Those people came to shake my hand and greeted me as a good Latter-day Saint. One man said, ‘I did not know there were such things in the Book of Mormon.’ That Negro family was permitted to come and were made welcome by all the members of the church.”[60]

The Howells finished their trip with a visit to former Latter-day Saint headquarters, Nauvoo, Illinois and then returned home to Salt Lake. Because of the small number of Black members in the church, the limiting priesthood and temple restrictions that were in place, and race issues of the time, the Howells concluded that segregated branches could not be sustained and they were never instituted.[61]

Not long after the Howells returned from their trip to the southern and eastern United States, Abner was widowed for the second time when Martha died on May 10, 1954. This loss did not keep him from remaining active in community and church affairs during the last years of his life. A year after Martha’s death Abner addressed a meeting at the First Unitarian Church on Sunday, Mary 15, 1955. He spoke to the forum as a past president of the Salt Lake Chapter of the NAACP.[62]

Shortly after Martha died, around 1955, Stephen L. Richards, who was serving as first counselor in the Church’s First Presidency, asked Abner to serve a unique mission. He and his mission companion, Claude Peterson, apostle Mark E. Peterson’s brother, would attempt to reactivate lapsed Black Latter-day Saints and encourage the children of baptized Black Mormons to also accept baptism. Richards prefaced his request by telling Abner, “It’s about time the Church did a little more than what we’re doing for the Negro race. . . . If we can get them to come back in, if they don’t want to mingle with us, we’ll build them a church of their own like we have done for the Spanish [speaking] people.” Abner and his companion succeeded in getting about twenty people to return to activity in the Church, but only for a short time. He believed the church leaders were trying hard, but it was an almost impossible task.[63]

At the completion of the Los Angeles Temple, early in 1956, LDS leaders opened it for public tours before its dedication. Abner had moved to California to live with one of his sisters and wanted to be one of the hosts for the temple tours. He applied, was accepted, and enthusiastically guided visitors through the new temple. He shared his faith and talked with them about the purposes of temple worship even though he would not be able to enter the edifice after it was dedicated.[64]

While living in Southern California Abner also volunteered his time speaking at firesides, seminaries, and at the University of Southern California LDS Institute. His audiences were anxious to hear his story and learn why he was a Mormon. Prior to becoming an LDS General Authority, Paul Dunn taught religion classes at the California Institute and often invited Abner as a guest speaker because Abner “could please his classes better than he could.” Abner could fill in the blank for the California students on the subject of Blacks and the priesthood in a way Dunn could not.[65]

Abner occupied an esteemed place as a faithful Black man who held on to his faith in a church that would not grant him the right to receive its highest ordinances. He spoke to various Latter-day Saint groups composed almost entirely of White members who listened with interest to his experiences in life and in the church. As author and scholar Margaret Young has pointed out, he seems to have put those members more at ease with their own misgivings about the fairness of their church’s racial policies.[66] While in California, likely around 1960, Abner told an LDS group what he believed his eternal reward could be, even without holding the priesthood and assured his listeners that he was satisfied with his view, even though he could tell some of his listeners were not, “The priesthood doesn’t save you. You can get to the highest degree of the Celestial Kingdom without the priesthood.”[67] Earlier in the talk, he shared his perspective, “The priesthood is one of the finest things on earth, it is also one of the worst things on earth because if you desecrate that priesthood, you won’t get as far as the fellow who doesn’t know anything about it.”[68]

Abner returned to Utah and lived with his daughter and her family in Salt Lake City until his death on September 7, 1966.[69] He was 88 years old. His funeral took place in the Valley View Fourth Ward in Millcreek, Utah where he had worshiped with his second wife, Martha. He was laid to rest in the Holladay Memorial Cemetery next to his first wife, Nina and five of their children.[70]

Several years before his death, Abner said, “I don’t know why I should live the life I’ve led, other than the fact that I have been called of the Lord to lead the life I’ve led. I have more friends in Salt Lake City . . . because I always walk down the straight and narrow path . . . doing the right thing.”[71]

by Tonya S. Reiter

[1] In an interview Abner gave later in his life, he told an undocumented, but detailed story about his family’s connection to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Abner said his father, Paul Cephas Howell, as a young enslaved boy, performed the duties of a valet to the man who held him in slavery. His slaveholder visited Arkansas, bringing young Paul with him. During that visit, Wilford Woodruff, who was serving a mission in Arkansas, met Paul and told him that someday he would be free and at that time, he should come to Salt Lake City. Abner believed that Elder Woodruff baptized his father at that time. This was his explanation for why his father had wanted to leave Louisiana and move West. Abner went on to say that after Paul Howell came to Utah, it was Wilford Woodruff who saw to it that he was hired onto the police force. Because of his height, Woodruff wanted him to guard the door to the newly built Salt Lake Temple. While standing on the temple steps, his height allowed him to see over the heads of the crowd. There is nothing in Latter-day Saint church records to substantiate these claims. The Paul Howell family did not participate in their local LDS wards in Salt Lake and no evidence has been found to document Paul or Eliza’s baptisms. Wilford Woodruff’s extensive journals do not mention the Howells while a missionary in Arkansas or after their arrival in Utah. See Wilford Woodruff, The Wilford Woodruff Journals, 6 vols. ed. Dan Vogel (Salt Lake City: Benchmark Books, 2020). Abner also mentioned his father’s baptism as an enslaved boy in a talk he gave to a church group.

[2] Byrdie Howell Langon, Utah and the Early Black Settlers, (self-pub., 1969), 3-6.

[3] “Paul C. Howell,” Salt Lake City, City Directory (Salt Lake City, Utah: R. L. Polk & Co., 1892), 388.

[4] Langon, Utah, 6.

[5] Langon, Utah, 7.

[6] Langon, Utah, 23.

[7] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Pasadena Stake audiotape collection, 1954-1958/Abner Howell’s testimony, undated, AV 1802/14!T0017, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[8] Abner Howell, undated tape recording of a speech to a Latter-day Saint group in Salt Lake, courtesy Howell family.

[9] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

[10] “Noted Athletic Figure is Dead,” Salt Lake Telegram, 25 May 1933, 12.

[11] “Langon, Utah, 26.

[12] “Denver Team Beaten 34-0,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), 30 November 1900, 6.

[13] “Denver Team Beaten.”

[14] “Home Boys Victorious,” Salt Lake Tribune, 30 November 1900, 5.

[15] “Noted Figure,” Telegram.

[16] Margaret Blair Young, “Abner Leonard Howell: Honorary High Priest,” 22 Sept 2015, paperzz.com, (accessed 10-27-22).

[17] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

[18] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

[19] “The Cadetship,” The Salt Lake Herald, 5 June 1897, 5.

[20] “The Cadetship,” The Salt Lake Herald, 12 June 1897, 8 and “Won the Cadetship,” Deseret News, 11 June 1897, 2. Earlier that spring, a young Black Cinncinnatian had won a cadetship at Annapolis Naval Academy. His appointment resulted in threats of resignation by students already enrolled at the school. See: “Colored Lad Gets a Cadetship,” The Salt Lake Herald, 15 April 1897, 6. Another article reported that the question of race prejudice had been settled at West Point. See: “Colored Prejudice North and South,” The Salt Lake Herald, 26 April, 1897.

[21] “Seniors’ Night of Fun,” The Salt Lake Herald, 6 June 1900, 5.

[22] Rachel Quist, “Paul Cephas Howell: First SLC Black Detective,” 11 February 2020, Rachel’s Salt Lake History, slchistory.org, (accessed 13 November 2022).

[23] “Negro Editors Meet,” Salt Lake Tribune, 7 August 1900, 2.

[24] “Colored People Celebrate,” Salt Lake Tribune, 13 May 1901, 5.

[25] “Abner Howell,” Salt Lake City, City Directory (Salt Lake City, Utah: R. L. Polk & Co., 1901), 838.

[26] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

[27] Langon, Utah, 26.

[28] Calendar of the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, 1904), 351, in Young, “Howell: Honorary High Priest.”

[29] University of Michigan, Michiganensian [1903], 194, 137.

[30] “Marriage Licenses,” Detroit Free Press, 31 August 1904, 6.

[31] “Abner Howell,” Detroit, City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R. L. Polk & Co., 1909), 579.

[32] “Abner Howell,” Salt Lake City, City Directory (Salt Lake City, Utah: R. L. Polk & Co., 1911), 524.

[33] United States 1910 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, Ward 3.

[34] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, 23rd Ward, Microfilm 26,712, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[35] Paul Ross telephone conversation with author, 28 October 2022. Abner listed his occupation as “Farmer” in the 1936 Salt Lake City Polk Directory possibly indicating he intended to devote most of his time to farming.

[36] United States, 1920 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, Precinct 1.

[37] Utah State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Death, Paul Cecil Howell, file no. 293, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[38] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Holladay Ward, part 1, CR 375 8, box 2896, folder 1, image 242, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[39] Kate B. Carter, The Story of the Negro Pioneer (Salt Lake City: Daughters of Utah Pioneers, 1965), 57.

[40] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

[41] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, “All Negro Blood, Baptisms and Confirmations for the Dead,” Salt Lake Temple, film no. F183511, 8, photocopied register of ordinance work done from October 14, 1924-June 15, 1942, John Fretwell Collection, held in private hands.

[42] Utah State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Death, Mary Juanita Howell, file no. 905, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[43] Carter, Negro Pioneer, 58.

[44] Howell, Pasadena tape recording.

[45] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

[46] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

[47] In fact, Elijah Able was ordained by a fellow priesthood holder in 1836; see W. Paul Reeve, “Elijah Able,” Century of Black Mormons.

[48] Howell, Pasadena tape recording. Howell also mentioned the McKay letter in his earlier talk tape recorded in Salt Lake.

[49] “Wait Convention Report,” Salt Lake Tribune, 2 Sept 1946, 8.

[50] “Union Nominates Slate of Officers,” Salt Lake Telegram, 21 May 1949, 14. “Laborers’ Local Elects President, “Salt Lake Telegram, 9 June 1950, 34. “Chest Passes Dead Line, Misses Goal,” Salt Lake Tribune, 27 October 1951, 19. “New Officers Chosen at Council Meet,” Deseret News ( Salt Lake City, Utah), 12 January 1952, 16.

[51] Carter, Negro Pioneer, 58.

[52] “Utah Society for U. N. Names Head,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), 23 May 1951, 10.

[53] “United Nations Association of Utah,” (accessed 28 August 2022).

[54] Utah State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Death, Nina Viola Howell, file no. 352, registrar’s no. 4, Utah State Archives, Salt Lake City, Utah and “Mary E. Howell,” Salt Lake Telegram, 10 February 1945, 9.

[55] “Martha S. P. Howell,” Salt Lake Tribune, 11 May 1954, 26.

[56] United States, 1950 Census, Utah, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, District 18-35.

[57] Margaret Blair Young, “The Black woman Who Served an Unprecedented Church Mission to Help Reduce Segregation, Prejudice in the Church,” (accessed 9 May 2022).

[58] Carter, Negro Pioneer, 59.

[59] Carter, Negro Pioneer, 59.

[60] Carter, Negro Pioneer, 59-60. The outcome of Abner’s address to the Hopes’ ward may not have been quite as successful as it seemed to Abner at the time. Len and Mary Hope continued to endure discrimination in their ward and relocated to Utah not long after the Howells visited them. See Joseph R. Stuart, “Len Hope,” Century of Black Mormons, and Joseph R. Stuart, “Mary Lee Pugh Hope," Century of Black Mormons.

[61] The LDS church has organized branches and wards based on spoken language which has produced some predominately racial or ethnic wards, but this has been a de facto distinction.

[62] “Forum Lists Speaker,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), 12 May 1955, 22.

[63] Howell, Pasadena tape recording.

[64] Carter, Negro Pioneer, 60.

[65] Carter, Negro Pioneer, 60.

[66] Young, “Honorary High Priest.”

[67] Howell, Pasadena tape recording.

[68] Howell, Pasadena tape recording.

[69] “Abner Howell,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City, Utah), 7 Sept 1966, 30.

[70] Abner Leonard Howell, FindAGrave.com.

[71] Howell, undated tape recording, Howell family.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.