Stevens, Lucinda Vilate Flake

Biography

Lucinda Vilate Flake represents the second-generation of Black Latter-day Saints to embrace the faith. In Lucinda’s case, she followed in the footsteps of her formerly enslaved pioneer parents, Green and Martha Ann Morris Flake.[1] Like her mother and father who converted as teenagers, Lucinda first accepted membership in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints at age thirteen. She was subsequently rebaptized in 1928, seven days following her 73rd birthday and on the same day that her grandson, Kenneth George Udell was baptized for the first time.[2] Lucinda remained a Latter-day Saint for the rest of her life and seems to have been influential in passing on the faith to the fourth generation of Flake descendants.

Lucinda grew up in a storied Black Latter-day Saint family. Her father, Green Flake first embraced the faith as an enslaved man in Mississippi in 1844. He was among the first forty-two Latter-day Saint pioneers to arrive in what would become Utah Territory and one of three Black enslaved men to enter the Salt Lake Valley on 22 July 1847. As such he was frequently honored as an original pioneer into the Valley and was regularly called on at Pioneer Day celebrations to commemorate his role.[3] There is no indication of how Lucinda perceived her father or what it might have meant to her to be the daughter of such an esteemed pioneer but given the attention he received in newspaper accounts, it must have had an influence on her sense of self.

Green Flake was not only a venerated pioneer but also a committed member of the Latter-day Saint faith. Following his arrival in the Salt Lake Valley, he chose to be rebaptized as an outward symbol of his devotion to the Latter-day Saint cause, this despite remaining enslaved to fellow Latter-day Saints James and Agnes Love Flake.[4] Lucinda would follow the same pattern as her father, with a rebaptism of her own late in life.[5]

Lucinda’s mother Martha Ann Morris, was also previously enslaved and also a Latter-day Saint. John H. and Nancy Crosby Bankhead enslaved Martha and brought her with them to the Salt Lake Valley. On one occasion Martha’s enslaver held her hand to a hot iron kettle until it “sizzled and fried” as punishment for a white child in Martha’s care who had accidentally put her hand on the same hot kettle. Lucinda’s mother thus lived with the visible scars of slavery for the rest of her life, something that must have left an impression of its own on young Lucinda’s mind.[6]

Lucinda was born on 2 December 1855, in Cottonwood Heights, along the east bench of the Salt Lake Valley. She spent the duration of her childhood there. Richard Howe of the South Cottonwood Ward performed her initial baptism on 13 June 1869.[7] Though there are no records to indicate what prompted her decision to be baptized or to explain why she was baptized as a teenager rather than the more typical age of eight, her parents were likely influential in her decision. Her baptismal record includes their names in the column for “parents”; then the clerk who created the record scrawled the word “colored” above the names of Martha and Green. Lucinda’s baptism thus marked a moment of belonging as well as a racial indicator that set her and her family apart.[8]

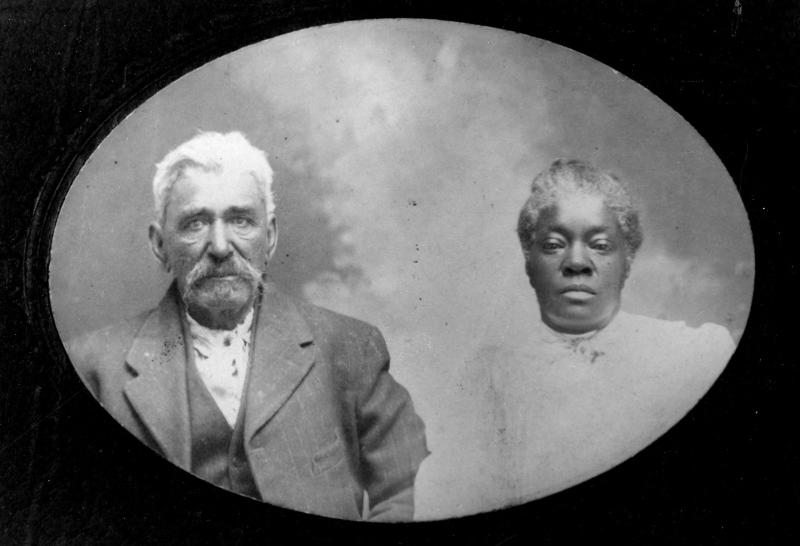

When she was 19 years old, Lucinda married 33-year-old George W. Stevens. George was born in Laredo, Tamaulipas, Mexico, and later immigrated to the United States. Census records consistently describe George as either a “black” or “colored” man even though his mother was Hispanic. Family tradition suggests that George and Lucinda met at a square dance; they were married on 3 July 1872 in Union, Utah. During their early years of marriage George joined Lucinda’s father in mining ventures alongside some of their Black and white neighbors. They developed claims with such names as “Union Blue” “Abraham Lincoln,” and Evergreen” in nearby Big Cottonwood Canyon.[9]

In 1882, an avalanche struck Big Cottonwood Canyon and led to tragedy. Lucinda and her husband George responded with care, bravery, and concern for their neighbors. The avalanche buried the home of a young family and no one knew if the six people who lived there had survived. Most people in the area favored leaving the house untouched in fear of triggering a secondary avalanche. However, Lucinda and George decided to risk their lives in order to save the people trapped below the snow. They dug through the snowpack in the hope of finding people alive but Charles and Eliza Hale Tackett and their four children had unfortunately died in the avalanche. Lucinda and George nonetheless retrieved the bodies. Despite not being able to save the family, Tackett descendants hailed Lucinda and George for their heroic efforts for generations after the event.[10]

Lucinda and George would go on to preside over a large family of their own. Lucinda indicated on the 1900 census that she had given birth to a total of thirteen children but only eight survived.[11] This was a typical and heartbreaking situation that many mothers-to-be faced in the late 19th century when mortality rates among newborns, especially those from Black families, were tragically high. Approximately 264 of every 1,000 Black newborns did not live to see their fifth birthday.[12] Lucinda lost five of her thirteen children, a rate higher than the national average.

By the turn of the century, the Stevens family had moved from Union in the southern part of the Salt Lake Valley, to Park Valley in Box Elder County in northern Utah. George worked as a farmer on the land they owned together, while Lucinda worked as a “canvassing agent.” Their older sons often worked with George as farmhands and Lucinda later listed her occupation as “housewife.” After a few years, the Stevens moved to Idaho Falls, Idaho where George and Lucinda purchased a house and George and their remaining children worked as “laborers.”[13]

It is difficult to determine the role that religion played in Lucinda’s life as an adult. She remained a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints but her husband did not join the faith and the couple’s children were not baptized in their youth. The 1880 federal census in Utah included an informal religious accounting which marked people’s affiliation (or lack thereof) with the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. The census taker marked George and all of the children in the household as “gentiles,” or people who did not belong to the LDS Church. For Lucinda, the census taker described her as an apostate Mormon, or someone who no longer practiced the LDS faith.[14]

Nonetheless, on 9 December 1928 Lucinda again entered the waters of baptism, this time as a 73-year-old woman. The baptism was not recorded as a “rebaptism” at the time, a practice that was largely dying out in the early twentieth century. It is not clear if Lucinda remembered her first baptism as a thirteen-year-old girl and she now wanted to recommit herself to the faith of her youth or if she perceived this later baptism as something new. Whatever the circumstances, she was baptized into the Idaho Falls Fourth Ward on the same day as her ten-year-old grandson, Kenneth Udell, marking four generations of the Flake family as Latter-day Saints. Lucinda may have simply viewed the occasion of her grandson’s baptism as an opportunity to join him in a show of devotion to the faith that her enslaved parents had sacrificed so much to embrace. B. F. Duffin, Jr., performed both baptisms while Alfonzo Y. Pond then confirmed Lucinda and Louis F. Nuffer did the same for Kenneth.[15]

George W. Stevens died at the age of 91 on 8 March 1930, in Idaho Falls of chronic valvular heart disease.[16] Even though he was never baptized into the LDS church, George’s funeral service was held in the Idaho Falls First Ward chapel and was presided over by Bishop James Laird.[17]

Lucinda lived for seven more years before passing away at the age of 82 on 21 January 1937, due to heart trouble.[18] Her funeral was held at the McHan funeral chapel and was presided over by T. T. Sessions of the Idaho Falls Fourth Ward Latter-day Saint bishopric. She was survived by her eight living children.[19] George and Lucinda were laid to rest next to each other in the Rose Hill Cemetery in Idaho Falls.[20]

By Wesley Acastre

with research assistance from Emma Lowe

[1] Amy Tanner Thiriot, Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah Territory, 1847-1862 (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2022), 57, 108-114, 143-145, 162-63, 220-226.

[2] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, South Cottonwood Ward, CR 375 8, box 6522, folder 1, image 97, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Idaho Falls 4th Ward, CR 375 8, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[3] Benjamin Kiser, “Green Flake,” Century of Black Mormons.

[4] Benjamin Kiser, “Green Flake,” Century of Black Mormons.

[5] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Idaho Falls 4th Ward, CR 375 8, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[6] Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 57; Benjamin Kiser and W. Paul Reeve, “Martha Ann Morris Flake,” Century of Black Mormons; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, South Cottonwood Ward, CR 375 8, box 6522, folder 1, image 97, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[7] United States, 1860 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Union; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, South Cottonwood Ward, CR 375 8, box 6522, folder 1, image 97, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[8] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, South Cottonwood Ward, CR 375 8, box 6522, folder 1, image 97, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[9] African Americans in Utah, Peoples of Utah Photograph Collection, Mss C 239, Box 2, No. 73, Utah Historical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah; United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Union; United States, 1900 Census, Utah, Box Elder County, Park Valley; United States, 1910 Census, Idaho, Bonneville County, Idaho Falls; United States, 1920 Census, Idaho, Bonneville County, Idaho Falls; Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 143-144.

[10] Thiriot, Slavery in Zion, 143-144.

[11] United States, 1900 Census, Utah, Box Elder County, Park Valley.

[12] Douglas C. Ewbank, “History of Black Mortality and Health before 1940,” (The Milbank Quarterly, 65 (1987): 100–28.

[13] United States, 1900 Census, Utah, Box Elder County, Park Valley; United States, 1910 Census, Idaho, Bonneville County, Idaho Falls.

[14] United States, 1880 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Union. For information on the 1880 religious census in Utah Territory see Samuel A. Smith, "The Wasp in the Beehive: Non-Mormon Presence in 1880s Utah," MS thesis, (Pennsylvania State University, 2008).

[15] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Idaho Falls 4th Ward, CR 375 8, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[16] Idaho, State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificate of Death, Falls, File No. 70166, Registered No. 49, George W. Stevens, Idaho State Archives, Idaho Falls, Idaho.

[17] “Rites Wednesday for Idaho Man,” Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah), 11 March 1930, 4; “Funeral Service - George Washington Stevens,” Idaho Falls Daily Post (Idaho Falls, Idaho), March 1930.

[18] Idaho, State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Certificates of Death, File No. 102074, Registered No. 14, Lucinda Stevens, Idaho State Archives, Idaho Falls, Idaho.

[19] “Mrs. Lucinda Stevens Succumbs on Thursday,” The Post Register (Idaho Falls, Idaho), 21 January 1937, 8; “Stevens Rites will be Conducted Sunday,” The Post Register (Idaho Falls, Idaho) 22 January 1937, 3; “Lucinda Stevens,” Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah) 23 January 1937, 32; “Rites for Mrs. Lucinda Flake Stevens are Sunday,” The Post-Register (Idaho Falls, Idaho), 25 January 1937.

[20] Lucinda Flake Stevens, Findagrave.com.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.