Innocence [3]

Why Robert Smithson chose a spiral for his Jetty, installed across the Great Salt Lake from the Bingham Canyon Mine, remains a mystery with several theories. One points to this Nabokov line found in Smithson’s notes: “the spiral is a spiritualized circle.” Or the nineteenth-century legend that told of a whirlpool in the middle of the lake opening to a subterranean route to the Pacific, which Smithson references in his Spiral Jetty film. Much has been made of the direction of his spiral. Smithson’s Jetty curls counterclockwise, as if reversing time. (The Bingham Canyon Mine curves clockwise.)

Though I’d lived in Utah all my life, I didn’t learn of Spiral Jetty until I was sixteen. A friend in English class mentioned he’d visited it over the weekend; I assumed it was the name of a hike. “It’s art” he corrected; “some guy built a giant spiral in the Great Salt Lake.” I thought he was joking. “How big is it?” “It’s so big you can’t see it all, you have to climb up a mountain a little ways and look down.” When I realized he was serious, I thought about this. “So, this was a crazy guy who lives out there?” “No,” he said. “He was somebody from New York or something.”

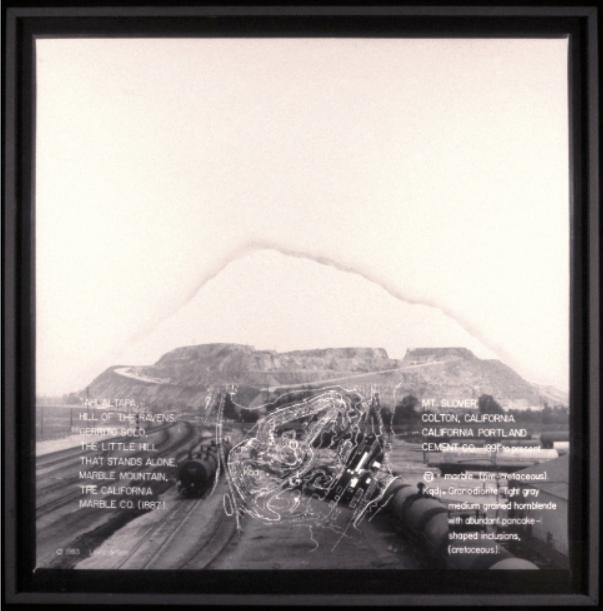

The memory of this conversation remains so crisp because this information distressed and embarrassed me. I was not embarrassed at having not known of Spiral Jetty, but on behalf of the artist. What sad bid for grandiosity would compel someone to do this? Did he think he owned the lake? I had never heard of land art. The closest thing to it I’d seen were petroglyphs, thousand-year-old marks on red sandstone, made by ancestors of the Ute, Paiute, Goshute, Shoshone, Hopi, and Diné people. I loved them; they were anonymous, inexpressibly old—they seemed to carry an inherent significance; they seemed to mark something, without ego.

In 1977, artist Anna Sofaer re-discovered a solar calendar built in Chaco Canyon, New Mexico, by the Anasazi, who occupied the area from 850-1250 A.D. Constructed at the top of a nearly inaccessible sandstone rise, now known as Fajada Butte, this calendar consists of two spiral petroglyphs and three leaning slabs of rock. Each day around noon, the slabs cast a thin dagger of light on the opposite wall. On the summer solstice, this dagger pierces the center of the largest spiral; on the winter solstice, two daggers surround its edges. The calendar also tracks the extreme positions of the moon, an eighteen- to nineteen-year cycle.

Sofaer had trouble convincing the scientific community of her findings. She once said “the last people to be impressed by the Indians are those who study most closely the originators of the sites.” The intricacy and precision of this calendar initially surprised experts, she said, “because we have put away the North American Indian heritage, buried it… to conceal our painful past.”8 Now an advocate for the preservation of the site and its continued study, she continually reminds her audiences of the threat nearby uranium and coal mining pose to the region.

And yet, some destruction sneaks in the front door. By 1999, tourist traffic to Fajada Butte had so eroded the site that one slab had settled, shifting the dagger’s position out of the center of the spiral.

Frank Lloyd Wright, in a 1947 telegram to Solomon Guggenheim: “ENTIRE MODEL NOW COMPLETED MOST EXCITING HARMONIOUSLY BEAUTIFUL USEFUL THING ON EARTH”.

8 Lippard, Lucy R. Overlay: Contemporary Art and the Art of Prehistory. The New Press, 1983.