Industry Economic Human Landscape

A Narrative of Promise

In Special Collections

At the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

Related Resources

In Special Collections

“Fortunately there no longer remains a barrier to the easy development of her great mines of gold, silver, lead, copper, zinc, iron, manganese, and antimony. Railway lines connect all the chief mining camps with Salt Lake City, and every advantage of civilization now favors the most remote parts of Utah.”(4)

“Nor are old localities entirely abandoned, for we see the same ravines worked again and again, even to the fourth and fifth time, and with satisfactory results...This kind of gold mining is utterly without limit, and as truly enduring as the hills. It is therefore safe to assert, that the prospects for successful mining are not at all gone, but even now, full of promise for the future.” (126)

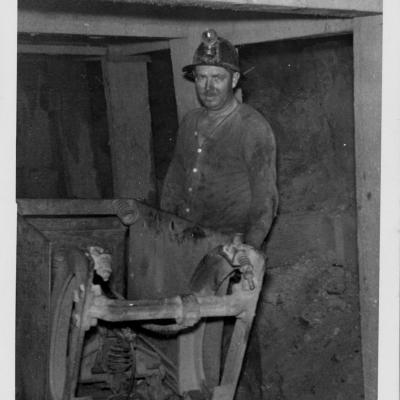

“This mine is equipped with modern hoisting machinery, commodious buildings, shops, and the ventilation of its interior workings, like that of every other mine in Eureka, is perfect.” (20)

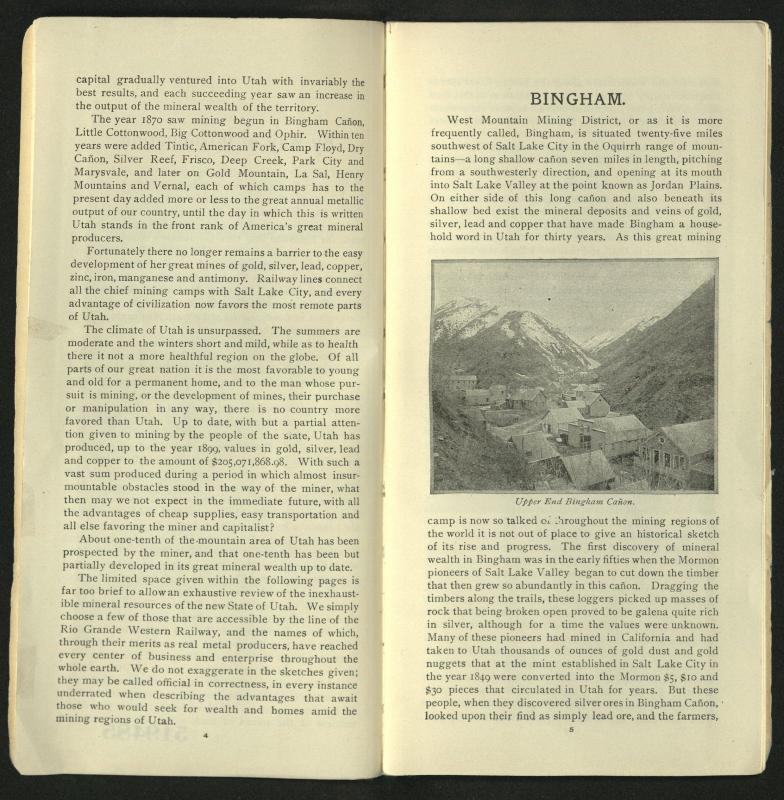

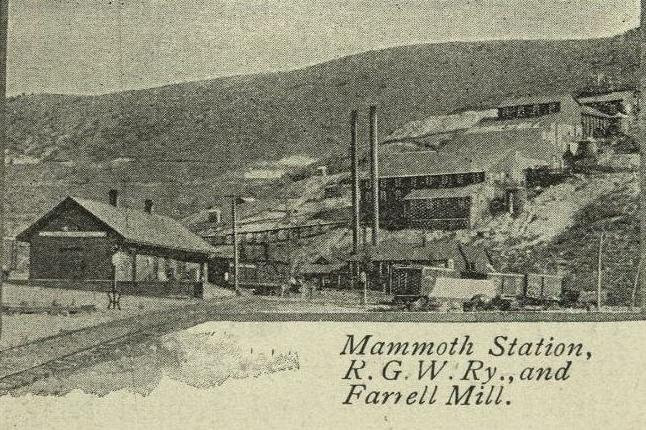

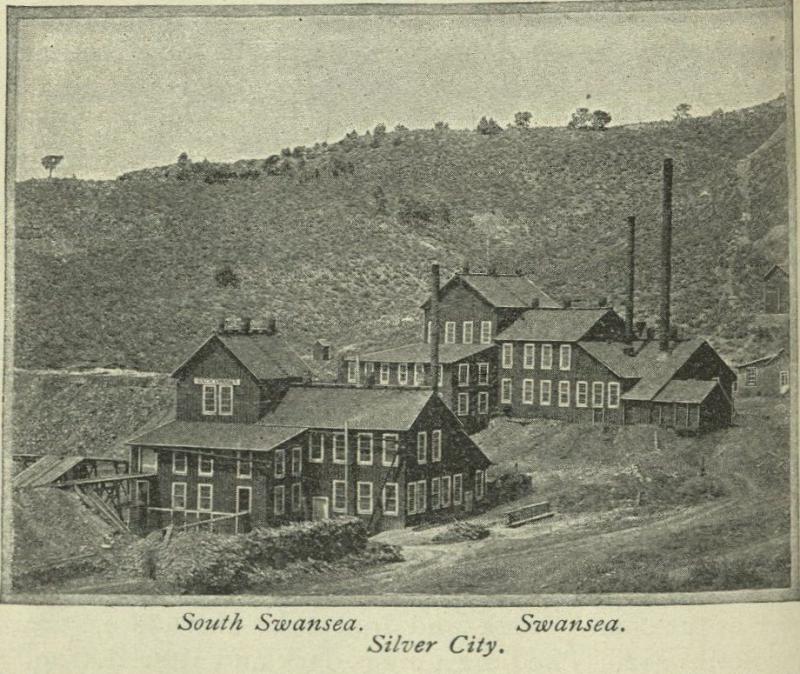

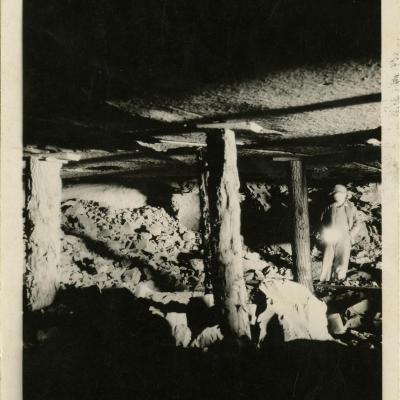

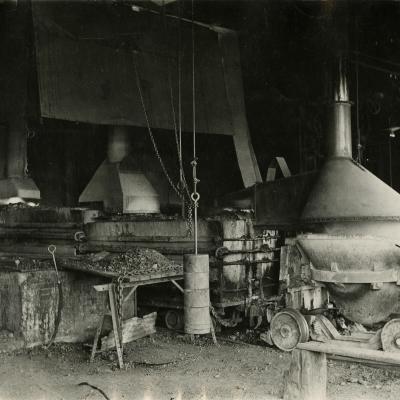

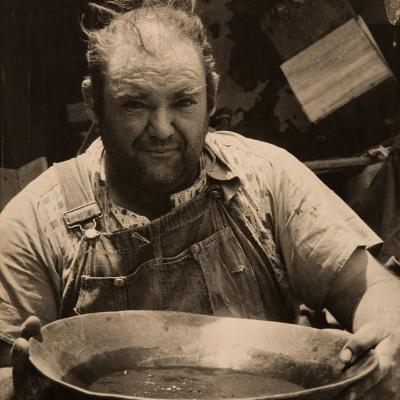

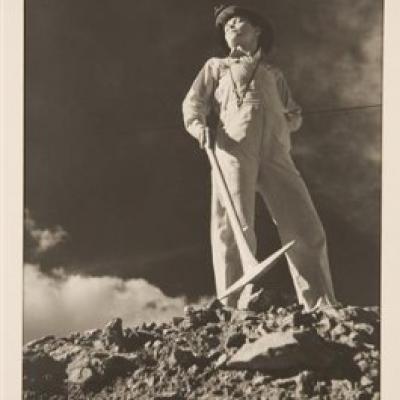

Nineteenth century guidebooks and promotional materials published by the mining and railroad industries document the voice of an era that sang the praises of progress westward and underneath the earth. Boasting plentiful mineral and employment prospects, the proponents wrote, “workingmen are well housed and fed, while the wages are such as to enable miners to save two-thirds of their pay.” (Outline History of Utah's Great Mining Districts: 38) Mining and ancillary industries like the railroads were similarly vested in luring laborers to the mines of the American West; increased production and shipments of ore, lumber, goods, and passengers resulted in increased profits for these businesses. Quaint illustrations and appealing texts depicted mining towns as clean, “civilized,” and modern, a far cry from the realities of the hard, dirty, dangerous labor in tunnels deep in the earth.

At the Utah Museum of Fine Arts

Thomas Moran, Wilhelmina Pass, Weber Canyon, Utah, ca. 1880s. UMFA2020.1.1.

British-born Thomas Moran (1837–1926), one of postbellum America’s foremost landscape painters, embarked on eight expeditions to the Western territories from 1871 to 1892. Moran’s artwork was widely reproduced and circulated during his lifetime, functioning for East Coast audiences as a pictorial narrative of the U.S. government’s ambitions to claim the western territories while testifying to the land’s immense potential for the still-evolving nation. Scenes marrying the grandeur of the natural landscape with man-made technologies had a particular appeal. Moran’s monochromatic palette aided publishers’ ability to easily reproduce the scene.

The unusual landscape formation depicted here is Devil’s Slide. Rising in parallel some 40 feet high from Weber Canyon’s walls, the two long, narrow ridges are formed by hard limestone layers; the gap between them, a softer shale mixture, eroded more rapidly than its exterior columns. This canyon was hotly contested during the transcontinental railroad’s construction, as both the Union Pacific and Central Pacific Railroads vied to be the first to lay tracks through the coal-rich canyon. While the coming of the train assisted mining interests in moving their goods, railway companies also circulated images like Devil’s Slide to promote the technological breakthroughs that enabled tourism on the rails.

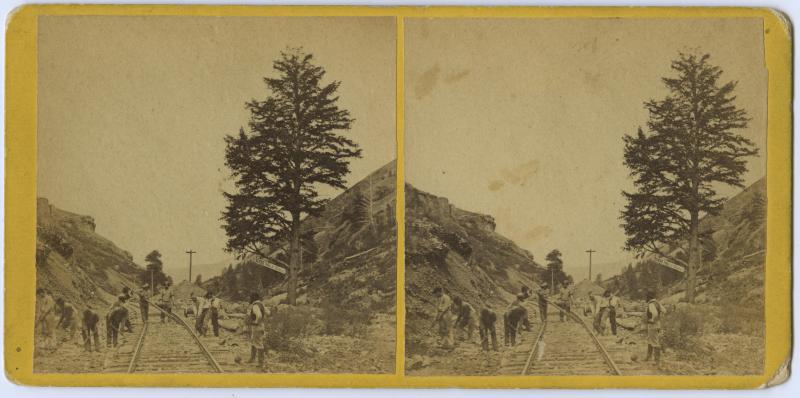

William Henry Jackson, 1,000 Mile Tree – Weber Canyon. UMFA1999.1.22.

In 1869, Union Pacific Railroad commissioned William Henry Jackson (1843-1942) to photograph scenes along the railroad’s routes for the company’s promotional campaigns. His photos caught the eye of geologist Ferdinand V. Hayden, who invited Jackson to work as his survey team’s photographer in 1870. The arrangement continued over the next eight years in a series of expeditions, with Jackson at times working alongside painters Thomas Moran (also in this exhibition) and Sanford Gifford.

While laying a particularly challenging stretch of track in Utah’s Weber Canyon, railway laborers noted a singular tree on the route. Upon discovering it lay exactly a thousand miles from the Union Pacific’s Omaha, Nebraska terminus, the landmark received its name. Railroad companies promoted distinctive landscape features such as the “One Thousand Mile Tree” in advertising campaigns, driving a flourishing tourist industry.

Soon after the tracks were laid, trains stopped alongside the Thousand Mile Tree for passengers’ enjoyment. Guide books touted the tree, along with Devil’s Slide and Wilhelmina’s Pass, as essential Weber Canyon views, and an excursion line from Ogden was built so tourists could take a pleasure trip to enjoy those features. Jackson was ultimately one of many photographers, lithographers, and illustrators who reproduced the unique tree’s likeness.

Pit Stops: Open Pit Mine Overlooks in the West, an exhibition by the Center for Land Use Interpretation, documents mine overlooks, a "sightseer-friendly frame for these man-made Grand Canyons, dramatic landscapes carved by explosives and machines–breathtaking and lingering monuments of our ongoing industrial age." (Organized by Aurora Tang)

Risk and Reward: The Western Uranium Boom, 1948–1970 presents first person accounts about hopes for wealth promised by the discovery of uranium. (Nate Housley)

The Copper Kings: Arizona, Utah, and Montana analyzes art that embodies both the hopes and realities of mining in the American West. (Betsy Fahlman)

Reclaimed Art, Reclaimed Land

Lesson Plan, 3rd Grade

Kimberly Andrade

This lesson focuses on the problems that come with mining the west and how there are potential ways to stop these problems maintaining everyday needs with more sustainable solutions. 3rd graders will learn about mining and reclaimed land, create a collage, and then will look at different ways to conserve Earth's environment. The lesson will culminate with a painting that reflects reclaimed lands over their collages.

Research and the Artivist

Lesson Plan, 8th - 12th Grades, Adaptable for Younger Audiences

Sydney Porter Williams

A lesson plan where students research Salt Lake City’s Inland Port, a relevant Utah issue. Students will evaluate the port as a design solution, choose a stance on whether or not they support the port, and create protest signs to back their decision.