Risk: Radiation

“This lung cancer that they’re trying to blame on uranium, from personal standpoint, I believe is mostly from cigarette smoke.”

Many at the time attributed high rates of lung cancer to smoking in the mines. The US Public Health Service suspected a link between radon and lung cancer, but the AEC delayed communicating this to miners. A 1948 AEC memo reads, “We can see the possibility of a shattering effect on the morale of the employees if they become aware that there was substantial reason to question the standards of safety under which they are working. In the hands of labor unions the results of this study would add substance to demands for extra-hazardous pay.” Later studies have been conclusive about the link between radon and lung cancer.

“The danger is there, yes. But whether our present standards are too stringent, I don’t know. As a miner I am probably biased. I feel that they are overly stringent… I don’t think there’s any more danger than there was in the various superstitions that if a man was around high-grade uranium for a very short time, he would become sterile. I never put much stock in this. I had a belt buckle that had a big piece of uranium on it at that time, and I wore it for a good while. I had three children following this.”

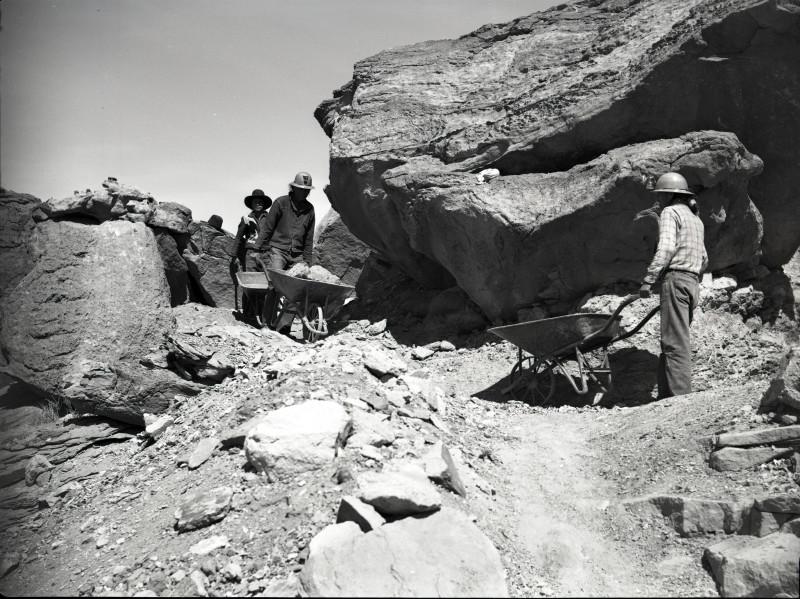

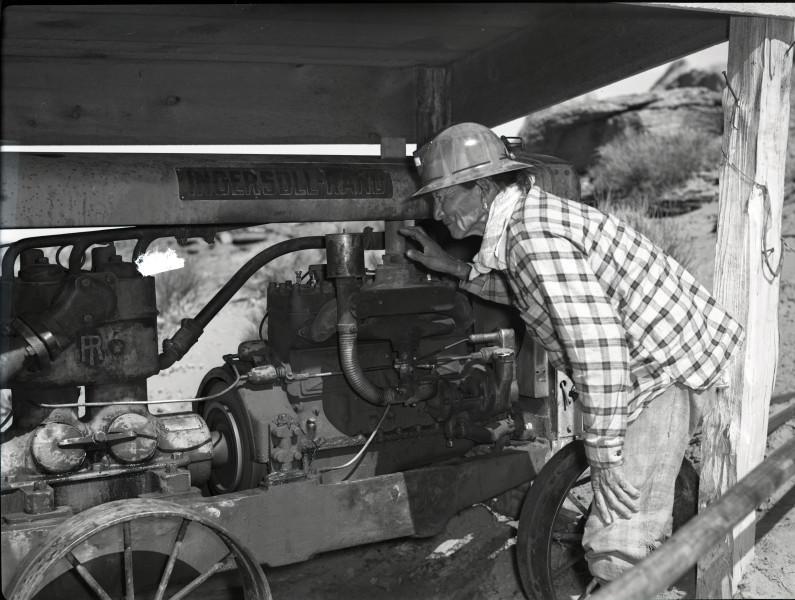

Ventilating mines became the recommended solution for maintaining tolerable levels of radon, though enforcement was lax.

Radon gas, a product of uranium as it decays, creates “daughter” products that pose a significant danger to uranium miners. The federal government throughout this period let the responsibility for miner safety fall on mine owners and state governments.

“Well, we probably might have been aware of [the ventilation problem]. We didn’t care. See, we were after money so we just kept going, going with the urgency. Now it’s taken its toll. But I don’t think it had anything to do with uranium being unhealthy. It was the dust we were getting in our lungs. We did have [health precautions], but we didn’t take them, you know, because like I said they didn’t enforce us to ventilate our mines."

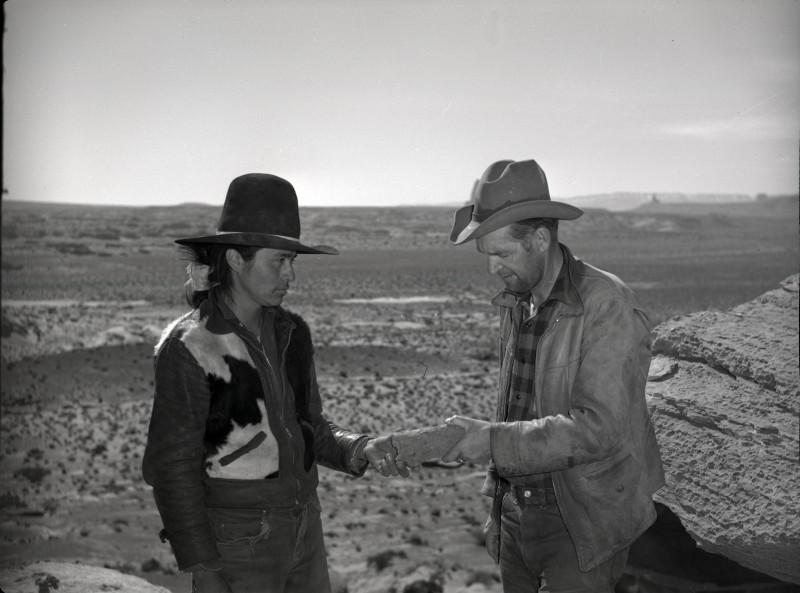

"If you mine on the reservation, you have to hire seventy-five percent [Navajo workers]. But one of the mines we had when we first went down there we didn’t have to hire any because it was a cleanup job, and the Navajo tribe wouldn’t let us hire them. They didn’t want us to kill any of them off.”

Prior to its use as fissionable material, uranium ores had long been used as pigment due to their bright yellow, red, and green colors.

"I was on a program in Primary, in a church children’s program, and I was an Indian. He used this red [uranium] oxide for putting on the war paint on me, you know. I’m not too sure how healthy it was now, but it was excellent war paint."

Uranium tailings, while sandy, are radioactive. Uravan was closed in 1985 and established as a “Superfund” toxic clean-up site.

John: “As we have said around here [in Uravan, Colorado, former company town of US Vanadium Corporation], our kids have played in the sandbox and eaten all of those tailings. Lorraine: “They’d go out and play in the sand because it was such clean sand.” John: “They weighed over 200 pounds and were over 6 feet tall.”

“I was appalled coming out of [atomic bomb research center] Los Alamos where everything was so strictly and constantly monitored with regard to radiation of any type, alpha, beta, gamma, the whole gamut. You couldn’t do anything there without a monitor being continuously at your side telling you, ‘Don’t go in there. Don’t do this. You have enough for a day, go home.’ [Then going] to Uravan where nobody knew anything about nothing with regard to radiation. Absolutely nothing. I was appalled. Of course as it turned out many of these houses were built on these old fills [from tailings] and they were hotter than hell [radioactive]. I hold the Atomic Energy as responsible for that nonsense. They knew this.”

“Right from the beginning they should have told the families to live away from the mine site. The mines were right there; that is the way the families lived. It was a dangerous substance, and they did not take care of us.” - Lorraine Jack, Navajo mother and resident of Shiprock, NM

“We thought we were very fortunate, but we were not told, ‘Later on this will affect you in this way.’ I am sure there is good money in the work, but if you compare life with money, money is nothing.” - George Tutt, Navajo Miner

“There was no safety. The men did not work comfortably then, too. They were forced to work. You were given instructions only once, and the next time you had to be told again, and then you were laid off. That is how the men worked. That was why the men did not speak up for themselves.. They did not say anything.” - Joe Ray Harvey, Navajo Miner

"My mother, she’s always said, ‘I’d wish you’d get out of those mines,’ to all of us, you know. Especially when the one brother was killed and [older brother] Merwin [lost an eye and a finger], but I always tell her that the mines have been good to us, you know. I mean, I don’t know. What is there that isn’t dangerous?"

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

All content © Nate Housley.