Race and Election Law

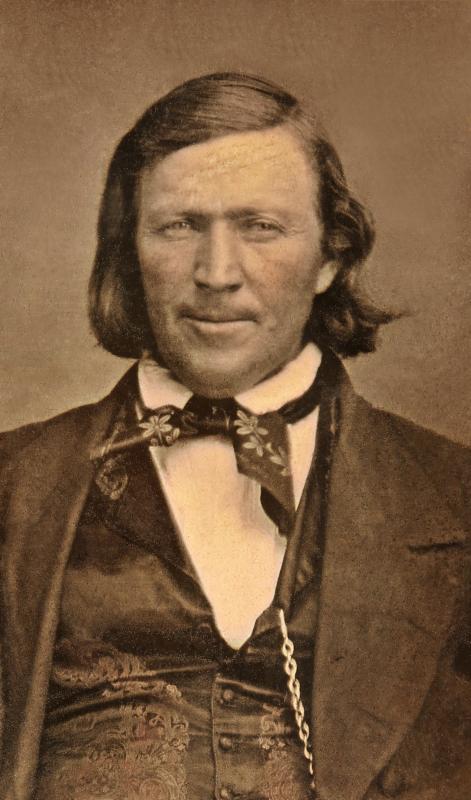

On February 4, 1852, the Utah territorial legislature passed a new election law; in doing so lawmakers stipulated that white men over 21 years of age could vote in the territory. The official legislative minutes do not indicate any opposition to the voting requirements in the election bill or mention any discussion on the subject. However, a few surviving sources indicate that councilman Orson Pratt firmly opposed any law denying Black men the right to vote. Pratt had already condemned An Act in Relation to Service and the Indian indenture bill and he now expressed concerns about racial equality in Utah’s election laws. As fellow legislator Hosea Stout recorded it, Orson Pratt voted against “all acts prohibiting the right of Negroes the privileges of voting.”[1]

By the mid-nineteenth century, white manhood suffrage had become the accepted practice throughout the United States. Over the previous sixty years, property requirements and other voting restrictions had crumbled along with some of the hierarchical assumptions of the early republic.[2] During the tumultuous 1830s, Jacksonian Democrats proudly championed the rise of the common man as a force in politics while conservative Whigs warned that the Republic had “degenerated into a Democracy.”[3] But at the same time that suffrage was expanding for white men, African Americans and other minority groups were being disenfranchised even in locations where they had enjoyed voting rights for decades.[4] Indeed, while Jacksonians fought tenaciously for equality among white men, they also fought for the continued dominance of white men over all other groups.[5]

Suffrage requirements enacted by Utah’s first Territorial Legislature in 1852 mirrored these national trends. During legislative debates in January and February, Brigham Young rationalized disqualifying Black men from the vote partially in terms of Jacksonian political theory. However, Young reinforced these ideas by insisting that God had placed a curse on Black Africans. Among other things, Young believed that this rendered people of Black African descent incapable of holding the priesthood and presiding in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Young taught that since men of African descent could not preside in God’s church, they should likewise be barred from participating in civil government. However, the disenfranchisement of African Americans was vigorously opposed by apostle and legislator Orson Pratt.

Similar debates in other states preceded Utah’s decision-making process and created a national context in which lawmakers used racial justifications to prevent Black men from voting.

The documents contained here correspond with the narrative history in Chapter 7 of This Abominable Slavery.

[1] Hosea Stout, On the Mormon Frontier: The Diary of Hosea Stout, 1844-1861, edited by Juanita Brooks, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press and Utah State Historical Society, 1964), 2:423.

[2] Gordon S. Wood, Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815 (Oxford University Press, 2009).

[3] Sean Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln (W.W. Norton & Company, 2005), 425.

[4] Alexander Keyssar, The Right to Vote: The Contested History of Democracy in the United States (Basic Books, 2000), 54-60.

[5] Jon Meacham, American Lion: Andrew Jackson in the White House (Random House: New York, 2008), 302-04; Daniel Walker Howe, What Hath God Wrought: The Transformation of America, 1815-1848 (Oxford University Press, 2007), 497-98; Wilentz, The Rise of American Democracy,192-195, 327, 507-18, 598-99.