Discrimination and Disparities in Recognition

Discrimination against women in educational environments and the workplace is widespread. A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center reported that 50% of women in STEM reported discrimination in the workplace, which is higher than the 41% of women in non-STEM fields (Funk & Parker 2018). Discrimination leads to disparities in recognition between men and women, and both lead to more women dropping out of STEM. Recognizing how discrimination affects the perceived success of women in STEM and the credit they get for their work is essential for understanding the gender gap in STEM.

Eliza Diggins is a theoretical astrophysicist and mathematical epidemoilogist, they discuss in their interview how discrimination in higher education causes women to drop out of PhD and postdoctorarl programs at higher rates comparatively.

"PhD advisors, generally speaking, have a higher rate of discriminatory activity against women in fields, particularly women in LGBTQ+ communities. And, you know, it does lead people to drop out of PhD programs. It leads people to drop out of postdocs. It's a problem, but I think largely it's just a cultural problem about science. I think we kind of teach people in authority positions in science to just kick people down because it's such a competitive field."

Implicit, or unconscious, bias often plays a role in discrimination, and can lead employers or institutions to prefer certain candidates based on factors like gender and race. Amy Sibul believes that when it comes to representation of women in science, we are taking the right steps, but we need more initiatives that address implicit biases at all levels, including professional expectations in academia.

"I think there are a lot of excuses that are made...and you hear this also around people of color, that there are not candidates in that category that really meet the qualifications. We need to reexamine those lists of qualifications to see where the implicit biases are because they exists there...I also think there is a historical unrealistic expectations of academia. Where you have to live and breathe this role of [being] a professor and not have hobbies, not be present in your children's lives, and everything is just high pressure. I think we do need to shift away from unrealistic expectations to healthy expectations."

An unconscious bias can lead to women getting fewer opportunities . This includes new projects or lab work. They can be completely overlooked for positions, despite having the same qualifications if not more.

"There were times when I was in a meeting and noticed my male peers were being given more significant opportunities… It wasn’t intentional, but I had to advocate for being included in those projects."

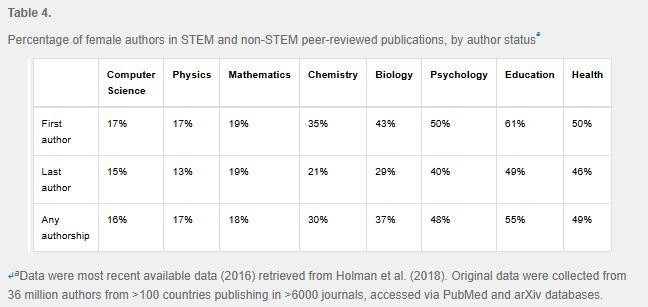

Underrepresented groups also face discrimination when it comes to getting recognized for their work. Researchers in can be recognized in two key ways. The first, is having their work published in scientific journals. The second, being selected for prestigious prizes and(or) awards. Women are under-recognized for both categories. If we look at the picture above we can see the data collected in 2016 from over 6,000 journals. This study shows that women are below the curve due to under or even misrepresentation. Even worse, women were the first author on 17% of physics publications and last author on 15%. (For context, the first author is usually the scientist that contributed the most to the project, while the last author is usually the principal investigator, or supervisor). Women are especially underrepresented when it comes to scientific awards. Data collected in 2018 show that women represented, “14% of recipients for the National Medal of Science, 12% for the Nobel Prize in Medicine, 6% for the American Chemical Society Priestley Medal, 3% for the Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 3% for the Fields Medal in mathematics, and 1% for the Nobel Prize in Physics.” (Charlesworth & Banaji 2019).

Dr. McKenzie Stiles discusses her experience in graduate school where she felt like she had to work harder than male students in order to receive credit and recognition for her work.

"I feel like I always had to work, maybe not twice as hard, but I always had to work harder than male graduate students who were at the same level as me. I had to present better and publish more and I still didn't feel like I got as much credit as my male colleagues. And honestly, that still happens. That's something that has not changed over time, which is really unforunate, and it's a little sad to say this, but you just get used to it, men getting more recognition than women in the field."

Page written and researched by Emilie Sjoblom and Sophie Jensen.

Later edited by Pamalatera C. Fenn