Tenure System

Tenure is a system that has remained a staple in university culture for years. However, the women scientists interviewed for this project had a variety of opinions on the matter. Cynthia Burrows, PHD, a longstanding tenured biochemistry professor. Who is a recent recipient of the highest-ranking award the University of Utah has to offer. Had a fairly optimistic viewpoint. However, her perspective might be due to the fact that she has been a tenured. Traditionally, she is a successful professor at her institution for decades. With a constant rate of publications and accolades for her work. In recent years, the process for initially attaining tenure might have changed significantly. Lisa Diamond, PHD's perspective suggests that tenure may be more problematic than it seems. From the perspective of many long-established scholars and scientists.

"Well, you really can't do research very well. You don't have your own choice in doing research and directing your own future, unless you're a tenure-line faculty member. That [being] said, there are some people who are extremely talented at teaching. And I think they like what they do. [You] only have to mention the name [of a member of the teaching faculty] and you know...she is so good at what she does. And I'm sure, I mean, I'm sure she loves what she does, but she's not involved in a research group. She's not involved in that aspect of it.

You know, she's got the personality for what she does. I'm not sure I do. I like teaching now and then. I don't think I would like doing multiple courses at a time and not being involved in research. So that's...what I think of the tenure system...somebody once told me tenure[...]. It's everything to people who don't have it and nothing to people who do. That's kind of right on those five years where you're building your portfolio. It seems like the most important thing in the world to get tenure.

Once you have tenure you go, 'Oh, I still have to work really hard. I still have to get grants, write papers , keep all of this research program going, and do a good job on my teaching.' Then you realize, 'Oh- 10 years now. No big deal.' However, you still have a lot of work.

Another friend of mine, a woman at Caltech. She tells her students, 'Did you ever think you wouldn't graduate from high school? Of course you'll graduate from high school. You're smart. You graduated from high school. Did you ever think you wouldn't graduate from college? Of course you're going to, I mean, do you ever think you're not going to graduate from college? No. You know, you're going to graduate from college, right? Then get a PhD, go on. So why would you approach tenure thinking you might not get tenure? That's the wrong way to think. Of course you will get tenure, right? So yes. You need to have a positive attitude about it. Then it probably will work out.'"

"You know it went fine for me, but you know I have a lot of - I mean it’s such a freaking weird system. Who came up with this? Now, to some degree, I've been more aware of how it has privileged me during the pandemic than ever before. Because, I never had to worry about my job. I knew that I was fine. Seeing how many people had their lives upended by the pandemic. Really made me aware of just the immense privilege of academia. That really does not exist in any other industry. It's kind of crazy.

I've had the opportunity to serve on a couple of different kinds of committees at the University. All universities have sort of review committees that if there's a dispute in a department about whether someone should get tenure. There are these upper level review committees that look at the case. I've served on those committees. So, I’ve had a chance to sort of see how the process works across the whole university.

It is just a deeply messed up system. I am so glad that I have tenure. However, I have so much ambivalence about its existence. I think my department does a really professional job of it. But you know when I...[have] a chance to review how other departments do it...In many ways, adults are just bigger-bodied third graders. Sll the same human frailties that we all carry around. I feel like the tenure system allows them to kind of flourish.

I also think that the university systems are not very good at finding ways to reward scholarships that may look a little different from what they're used to. One's that may have a different trajectory than most. Scholarships that takes longer or that's more community-engaged, or that doesn't yield the same number of publications. It's like there's a certain model of what success looks like at the university. As much as people like to talk about being inclusive and representing diverse forms of scholarship. When it comes down to it, when people produce knowledge that doesn't fit the mold that they're used to. It is really hard to get that work acknowledged and validated."

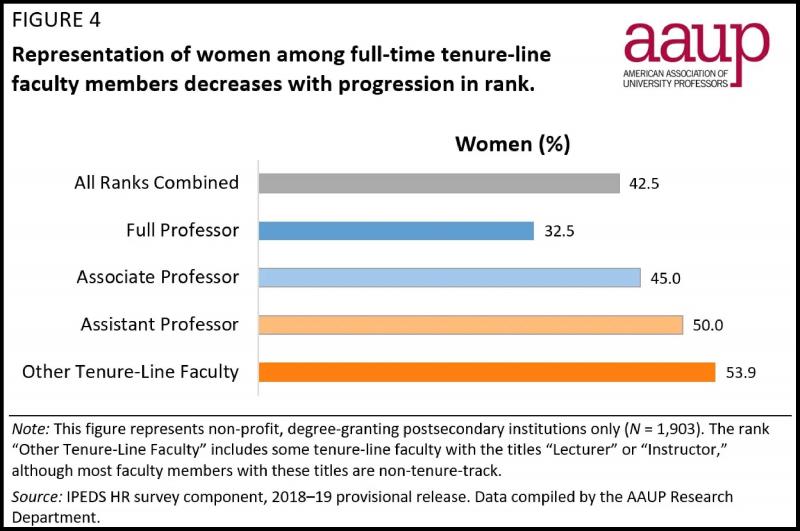

Despite the fact that an increasing number of women have attained advanced degrees and are reaching higher positions in academia nationwide. There is still a very pervasive culture that creates an environment where women go without sleep. Put off their personal or family-building goals. Or make more emotional sacrifices than their male counterparts, in order to maintain pace with an increasingly breakneck academic achievement cycle. Moreover, the data clearly indicate that while women are well represented at lower ranks in the tenure system. At higher ranks, their numbers drop off.

For example, in 'Sleepless in academia,' Acker and Armenti analyze this phenomenon by summarizing the recent improvements in inclusion of women in academia. Coupled with personal accounts of exhaustion, burnout, and issues that women faced while trying to move upwards in their respective academic systems:

"Policy reform stimulated by societal change has improved life for women faculty members. They now rarely have to fight against nepotism rules that screen them out of jobs when their partners are in the same institution; they have maternity leaves and sometimes, in North America, the option of slowing the tenure clock. Their representation in the university has risen. In Canada, the number of full-time faculty posts held by women has increased by 2000 since 1992, while those held by men have decreased by 5000, although the decrease is due to male retirements rather than disproportionate female hiring. Women account for slightly over one third of new appointments, consistent with their representation among doctoral recipients in the past decade, and they are about 30% of all full-time academics. In Britain, figures from the Equal Opportunities Commission (2001) indicate that women were 32% of full-time and 47% of part-time academic staff in higher education institutionsin 1998–1999. While in both countries, men still dominate higher ranks and managerial positions, women's representation at that level is also gradually increasing (Wyn et al., 2000). (4) These changes make it more difficult to argue that women are a minority group within academia, subject to exceptional deprivations and degradations. Yet, as we shall see, certain disadvantages persist.

Commonly emphasized by the women in our studies were the high levels of stress, exhaustion, and sleeplessness associated with combining the building of an academic career with bringing up young children. Apparent in the women's comments were concerns about self-esteem and self-presentation. Madeleine's anxiety was related to ‘the fact that you have to keep justifying your existence, to outside agencies, even to your Dean’. Coiner's (1998) discussion allows us to make a connection with the family issues discussed in the previous section, as she describes ‘coping well’ to be one of the ‘unspoken requirements for tenure’. However hassled, junior academics should ‘look relaxed and on top of things rather than frenzied, fatigued, malcontent. We have to prove that we're ‘‘one of them’’... Most of the untenured faculty I know believe that they would jeopardize tenure by making demands or simply by admitting the truth about the quality of their lives’ (p. 240). Obtaining tenure did not necessarily bring relief. Terri, for example, said that ‘I still work about 78 hours a week which is crazy... I mean I'm in my mid-forties, I've got tenure.'"

Page written and researched by Abigayle Kendall, Kaylee Martin, Rachel Nelson, and Eva Quintus-Bosz.

Later edited by Pamalatera C. Fenn