James, Sylvester

Biography

When Jane Manning gave birth to a son in the spring of 1838, her mother was there to guide her through the challenging days that every new mother—but especially a teenage mother—would pass through.[1] Jane, a free Black adolescent who worked as a domestic servant in New Canaan, Connecticut, was unmarried but not alone. With her family home in nearby Wilton, her mother, brothers, and sisters likely provided Jane and her baby the comfort and aid of close kinship. Jane named her son Sylvester, but she kept his father’s identity to herself.[2]

Sylvester spent his earliest years under the care of his mother and extended family.[3] In both homes, he would become accustomed to the daily devotions of a religious household. Prayers, hymn singing, and visits to the New Congregational Church where his mother and grandmother worshipped would have been familiar routines. When Sylvester was four years old, his mother attended a meeting held by missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. On hearing their message, Jane recalled that “I was fully convinced that it was the true gospel he presented and I must embrace it.”[4] The following week, the missionaries baptized Jane into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Perhaps Sylvester was among those who stood on the riverbank to see Jane wade into the currents and commit her life to Jesus and join an upstart faith. It would be the first of many baptisms he would witness. Many of Sylvester’s family, including his Aunt Sarah and Uncle Isaac, followed Jane into the church. The family’s subsequent devotion to their new faith would dramatically alter the course of Sylvester’s life.[5]

These conversions gave Sylvester’s religious world a new language. His family talked of gold plates, prophets, and a faraway place called Zion where Mormons would build a community of believers. The following year, the Manning family left Connecticut to join the Latter-day Saints gathered in Nauvoo, Illinois.[6] For five-year-old Sylvester, the journey brought new landscapes, strange faces, and likely his first ride on a canal boat. It also brought danger. Although Jane and Sylvester’s generation of the Mannings had never been enslaved, widespread racial prejudice exposed the family to discrimination and wrongful detainment. Part way through their journey, the Mannings realized this fear when officials denied them passage by canal because they lacked “free papers.”[7] The Mannings would have to complete the journey on foot.

Jane’s recollection of this thousand-mile migration describes cold river crossings and walking in tattered shoes that caused their feet to crack and bleed.[8] Sylvester’s family likely shielded him from the full force of these hardships. He would have felt hunger and exposure, but also adventure, intense familial closeness, and spiritual outpourings. Sleeping on the ground was no chore if he could feel his mother and grandmother beside him. When Sylvester’s legs were tired, maybe his Uncle Isaac swept him up on his shoulders to rest. Perhaps a worried Sylvester lingered near his mother’s bent figure the night she prayed for their sore feet to be healed. When his family woke to find their prayers answered, he was with those who “went on [their] way rejoicing [and] singing hymns.”[9] For young Sylvester, this religion was not so much a church to visit, but rather a field to pray in and a song to walk to.[10]

Sylvester’s arrival in Nauvoo in late 1843 likely came with a mixture of emotions. His mother’s much-anticipated meeting with Joseph Smith brought an invitation for Jane to take a position at the Smith’s Mansion House as a domestic servant. Sylvester’s Uncle Isaac also obtained work as a cook for the Smith family.[11] The remainder of the “little band” of Mannings secured work and housing elsewhere, dividing up the only family Sylvester knew.[12] As perhaps one of only a small number of Black children in Nauvoo, his presence elicited some curiosity, especially from those who noticed the conspicuous absence of Sylvester’s father.[13]

Recollections from Jane and her brother Isaac suggest that their employment with the Smiths cultivated familiar—perhaps even familial—affections. Sylvester, who stayed with his mother in the Mansion House, likely shared these feelings.[14] The kindness from Joseph Smith and his family reinforced what the Mannings “perceived to be a prophetic mantle” that “cement[ed] their commitment to the Latter-day Saint cause.”[15] Their treasured association with the prophet would also distinguish Sylvester, Jane, and Isaac among Latter-day Saints throughout their lives.[16]

The mob that took the lives of Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum in the summer of 1844 thrust Sylvester into a period of upheaval. Sylvester’s mother Jane found employment with church leader Brigham Young. While working for Young, Jane married Isaac James, a Black Latter-day Saint convert also working for Young.[17] In the spring of 1846, the newly formed James family left Nauvoo and began the 266-mile journey to join other Latter-day Saints at Winter Quarters. His grandmother, aunts, and uncles, however, chose to remain behind. This family separation may have saddened Sylvester, but with the arrival of a baby brother named Silas in June, perhaps he was too busy to notice.[18]

The James family would spend a year in this temporary city where hunger and poor sanitation sickened thousands and killed hundreds of their fellow Saints. Even under such challenging conditions, Latter-day Saints continued to attend church services, perform baptisms, bless their newborns, and marry. At eight years old, Sylvester would have been eligible for baptism into the church during his time at Winter Quarters, but no record of this key ritual has been discovered. Even still, he is consistently counted as a member of the Church in records created in Utah Territory despite the absense of a baptismal date. [19] By Sylvester’s ninth birthday in March of 1847, leaders had organized many Latter-day Saints into companies in preparation for their final trek west. On June 18, 1847, the James family embarked for the Great Basin.[20]

Sylvester’s journey to the Great Basin would look much different than his walk to Nauvoo four years prior. Instead of traveling in a small family group, the James family emigrated in companies of fellow Latter-day Saints.[21] Like many children who migrated west in the nineteenth century, Sylvester would be tasked with responsibilities beyond his years.[22] In addition to helping his family with the routine chores and meals, he probably learned to drive oxen, herd cattle, and hunt for small game. These experiences helped Sylvester develop valuable skills and grow into his role as a brother, son, and member of the Latter-day Saint community. Most importantly, the journey transformed Sylvester into a pioneer—an identity he embraced throughout his life.[23]

On September 22, 1847, Sylvester made the long descent into the valley he would call home over the next sixty years.[24] After their arrival, the James family rejoined the employ of Brigham Young, who would replace Joseph Smith as president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. From age nine to about seventeen, Sylvester lived with his family in a home on Young’s property in the centrally located Eighteenth Ward. In the shadow of the church president, he grew into adulthood.[25]

Sylvester’s formative years established him as a central cog in the family economy and a steady figure in his home life. While living in the Eighteenth Ward, brothers Sylvester and Silas welcomed three sisters to the family: MaryAnn (b. 1848), Miriam (b. 1850), and Ellen Madora (b. 1853). Because Sylvester was eight years older than the next oldest sibling, he carried an outsized responsibility in providing the growing family with much-needed support. As the oldest of five children, Sylvester would be expected to provide a heavy share of labor in the form of household chores, maintaining animals and land, and caring for his younger siblings. Like many early settlers, he also faced chronic hunger due to successive crop failures that left pioneer orchards and farms with insufficient food to adequately feed its growing population.[26]

As Sylvester matured, he would also gain awareness of the racial prejudices around him. By the 1850s, the population of Black individuals in Salt Lake Valley was comprised of free-born individuals like Sylvester, former slaves, and people who remained enslaved by those emigrating to Utah Territory.[27] Perhaps Sylvester was troubled to encounter enslaved Black Latter-day Saints; it’s possible that he was even mistaken for being enslaved himself.[28] In his community, Sylvester would have been at the edge of belonging: a Latter-day Saint, pioneer, and employee of the prophet, yet excluded from the full fellowship of the social and religious life enjoyed by his white counterparts.

For most of his childhood, Latter-day Saints held a variety of conflicting positions regarding the standing of Black individuals both in society and within the church.[29] Sylvester’s proximity to both Joseph Smith and Brigham Young could have made him privy to discussions on race. As Latter-day Saints gathered in Utah Territory, the mix of free and enslaved Black and Native American individuals threatened to disrupt the social order. Sylvester was fourteen when Brigham Young and the Territorial Legislature formally addressed these concerns.[30] The resulting law—in part—offered a conservative form of gradual emancipation for enslaved Black individuals but freed no one that was then enslaved. It prohibited mixed race sexual relations and Brigham Young’s speeches from the legislative session articulated a theology of Black exclusion from priesthood office and temple ordinances.[31] For Sylvester and his family, these were not simply regulations in the abstract; the language of prejudice spoken in government halls and over pulpits likely flowed into the hearts of his friends and neighbors. Moving forward, the hardening of race-based religious and social segregation after 1852 would become a barrier to the belonging that was otherwise his to claim.[32]

Around 1856, eighteen-year-old Sylvester moved with his family to a home in the southeast corner of Salt Lake City. No longer under the employ of Brigham Young, the James’s acquired oxen, hogs, and chickens, as well as land and farm equipment. [33] Sylvester likely shouldered much of the labor this economic growth would demand. In addition to driving wagons, he would have learned to care for a variety of animals, plow fields, and cultivate crops. An 1859 tax assessment on the James property suggests that their hard work had paid off. In light of the economic hardship exacted on Latter-day Saints during the Utah War (1857-1858), these modest but steady gains were particularly impressive.[34]

Little is known of Sylvester’s social and religious life as a young adult, but some evidence points to his good standing among his peers. News of the Civil War, along with persistent tensions between Latter-day Saints and federal appointees, triggered the revival of the Nauvoo Legion Militia in Utah. Legion membership records from late 1861 reveal Sylvester’s membership in the Second Battalion of the Second Brigade of the First Regiment of infantry.[35] “Since membership in the Legion was legally restricted to white men,” notes historian Quincy Newell, “Sylvester’s participation was significant.”[36] Perhaps the exigencies of war caused militia leaders to ignore this restriction. It’s also possible that the militia saw the restriction as outdated or unnecessary. Regardless of the reason, Sylvester’s inclusion suggests a contingent fluidity to racial boundaries and a recognition of his worth as a militia member.

As the James family continued to grow, Sylvester looked ahead to starting a family of his own. By 1864, Isaac and Jane had six children aged five to sixteen.[37] Now in his mid-twenties, Sylvester would be focused on his future. As he became acquainted with a handful of other Black families in the area, he met Mary Ann Perkins, a formerly enslaved woman whose family came to Utah as the property of Reuben Perkins.[38] Around 1865, Mary Ann and Sylvester married and moved to a property of their own near 800 South and 900 East, about one block from Jane and Isaac.[39] In late 1866, they welcomed son William Henry, followed by a daughter, Esther Jane, in 1869. [40]

Sylvester’s departure from his family home coincided with increasing marital friction between Jane and Isaac. At the same time, his sisters Mary Ann, Ellen, and Miriam showed signs of restlessness with their home life. Between 1867 and 1868, each of these sisters left the family home while still in their teens. In early 1870, Jane and Isaac divorced, and by the fall, Jane moved her family closer to the center of Salt Lake City.[41] Miriam married Joseph Williams and lived in Salt Lake City with their two young daughters, Estella Elizabeth and Josephine Isabel.[42] His sister Mary Ann now lived in the railroad town of Corrine, Utah with her two-year-old, Isaac.[43] Eighteen-year-old Ellen Madora, along with her one-year-old daughter Malvina, lived at home with her mother and siblings—at least for the time being.[44] Despite being married with a family of his own, Sylvester likely held an abiding concern over the well-being of his mother and siblings. Having been raised by a single mother for much of his childhood, Sylvester would have been sensitive to his siblings who faced similar circumstances.

Sylvester did not know it then, but that year marked the beginning of what would be several years of losses. On the heels of his mother’s divorce, his sister Mary Ann had a second child, Joseph, who died of pneumonia at three months of age.[45] The following year, Mary Ann moved from Corrine to her mother’s home in Salt Lake where she would deliver her third son, Henry James. Tragically, complications from childbirth would take Mary Ann’s life.[46] A week later, her newborn Henry would succumb to “lung disease,” and both mother and child would be buried together.[47] We can imagine what heroics Jane undertook to revive the health of her daughter and grandson, only to lose them both. On the heels of this family sorrow, Sylvester and his wife Mary Ann would welcome daughter Nellie to their family.[48]

In a devastating turn the following year, Sylvester would lose his brother Silas to tuberculosis.[49] While Silas’s diagnosis made his gradual decline and passing somewhat foreseeable, it could not lessen his brother’s grief. Like most children in blended families, Sylvester probably harbored complex feelings about his mother’s marriage and Silas’s birth. We can imagine nine-year-old Sylvester, weary from walking, jostling the unwieldy one-year-old in his arms on the trek west. How often did Sylvester scoop him up as he crawled through the dirt or toddled dangerously near a fire? As Silas grew, Sylvester would have become his teacher and protector. When Silas was finally old enough, he could be Sylvester’s playmate and work companion. Silas’s death may have also stirred feelings of anger toward his stepfather Isaac, whose departure left Sylvester and his mother with heavy burdens to shoulder during these crises.

In the wake of Silas’s death, both Sylvester and Jane appeared in probate court to settle matters of property. On July 1, 1872, Judge Elias Smith determined Sylvester to be the owner of all 1.25 acres of Plot 3 on Block 13 in the First Ward. [50] Sylvester continued to farm his land and make improvements, but in May of 1874, he experienced a setback. “Yesterday,” the Deseret News reported, “the stable of Mr. Sylvester James, a half breed… took fire and was soon wrapped in flames.” Despite the efforts of many to put out the fire, the building was a total loss. While Sylvester managed to save his team from the fire, the newspaper estimated that the loss of the stable and farming implements at two to three-hundred dollars. Though the amount in itself was small, the paper reasoned, it “is considerable to Mr. Sylvester James who is a workingman.”[51]

Exactly one month later, Sylvester’s eight-month-old niece Nettie contracted whooping cough and died on June 19, 1874.[52] Just ten days later, Sylvester’s own five-month-old son and namesake would succumb to a lethal spider bite.[53] Nettie’s mother Miriam, who never fully recovered from the delivery, passed away from “child bed” that December, fourteen months after giving birth.[54] In a short span of time, Sylvester would mourn three siblings, a son, two nephews, and a niece.

The eternal salvation of family and loved ones who had died appeared to be on the minds of many Black Latter-day Saint families, including the James’s. In the aftermath of these deaths, Sylvester’s mother Jane and wife Mary Ann joined a group of Black Latter-day Saints invited to the Endowment House to perform proxy baptisms for deceased friends and family members.[55] Sylvester did not attend. His absence may not have been significant, but perhaps it signaled a religious divide that began to form between Sylvester and his wife Mary Ann. On January 3, 1882, their children William (age fifteen), Esther Jane (age twelve), and Nellie (age ten) were baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints by a white elder in their ward.[56] That their children were not baptized at the customary age of eight hints that there was some hesitancy or delay, perhaps on the part of Sylvester. That the baptisms happened at all, however, suggests that the children’s desire (and more likely that of their mother) to be a part of the Latter-day Saint community ultimately won the day.

Sylvester’s growing disassociation from the Latter-day Saints was compounded by his reputation for heavy drinking.[57] In oral histories conducted with Sylvester’s descendants, family members recite Sylvester’s longtime struggle with alcoholism with a mixture of pathos and humor. “He bought liquor in jugs. He didn’t buy it in bottles,” recalled his granddaughter, Henrietta. “He would get drunk and I’d be so happy. He’d take and buy me a sack of candy. The girl in the store was scared of him . . . and she would give him a sack this big.” [58] His wife Mary Ann would likely tell a different story. Perhaps it is too easy to link Sylvester’s pain and trauma with this self-medicating behavior. Still, it isn’t difficult to imagine how this addiction could flourish in the face of family trauma, religious disaffection, and perpetual discrimination.

Sylvester was not shy about expressing his feelings on Latter-day Saints who had failed to extend fellowship and kindness. When recalling his strained relationships with church members, his descendants said,

[H]e called Mormons ‘the crookedest people on God’s earth’ and ‘prejudiced and liars and thieves.’ He ridiculed his wife for going to church with ‘them hypocrites.’ He especially did not like Brigham Young. [59]

While the specific circumstances that brought Sylvester to these opinions remain unknown, possibilities abound. For the better part of ten years, the James family would remain in the employ of Brigham Young, giving Sylvester a close-up view of the church’s leadership. Perhaps he blamed Young for the church’s policies of racial exclusion or experienced how these racial prejudices bled into everyday business, family, and community interactions. A descendant of Sylvester’s father-in-law Frank Perkins speculated that Sylvester’s disaffection stemmed from an excursion to San Bernadino that he took with a company of Latter-day Saints.[60] They also shared how Sylvester’s lighter skin fueled talk about his mysterious paternity.[61]

The ecclesiastical exclusions that kept him from the fellowship of priesthood quorums also had social and economic implications. As a young laborer, did he receive a fair wage? When he was old enough to purchase and farm his own land, was he dealt with honorably? Would he have felt welcome at church picnics, dances, and theatrical performances? Perhaps his sisters’ decisions to leave their home and faith sent tongues wagging among his neighbors.

In 1885, Sylvester’s estrangement from the church came to a head when the bishop of his congregation excommunicated Sylvester for “unchristianlike behavior.”[62] This was a blow both to his mother Jane and his wife Mary Ann, both of whom remained firmly in the church. Whether Sylvester’s feelings stemmed from a few harmful incidents or a lifetime of injustice, it formed a wedge in his marriage that would remain to the end of his life.

Still, Sylvester remained an important figure in his immediate and extended family. In an account from the Salt Lake Herald from January 12, 1887, a “frail colored girl recently jugged for vagrancy” called on Sylvester, “a well-known colored man,” to retrieve her personal belongings from a rented room in a secondhand store. The unnamed girl was possibly Sylvester’s sister Ellen Madora, who had recently returned to Salt Lake after working in Nevada and San Francisco.[63] When Sylvester arrived with his wagon, however, the store owner attacked Sylvester with a three-foot iron drill, causing a serious gash in his head. Sylvester filed a complaint, and police charged the store owner with assault. At the trial, the judge found the owner guilty, noting that Sylvester would likely suffer from the blow “as long as he lived.”[64] This incident reveals the complexity of Sylvester’s family life and standing in his community. While he encountered prejudice and even violence, he could also assert his rights under the law. Sylvester’s connection to his mother may also have won him a degree of trust and respect he may not have otherwise enjoyed.

For the first twenty-two years of their marriage, Sylvester and Mary Ann lived and farmed on their property at 800 East and 833 South.[65] They welcomed four more children during these years: Albert Sherman (b. 1876), Nettie (b. 1877), Manissah (b. 1881), and Mary Ann (b. 1885). Tragically, they would lose as many in the same time span. Albert lived just four days, and Manassa, six months. On December 8, 1887, their sixteen-year-old daughter Nellie died after contracting pneumonia. A month later, their three-year-old daughter Mary Ann died from “inflamed lungs,” followed by Sylvester’s father-in-law Frank Perkins one week later. By 1888, just three of their eight children—William, Esther, and Nettie—remained.

Under these circumstances, Sylvester and Mary Ann determined to leave their home in Salt Lake’s First Ward. Perhaps Mary Ann could not bear to wash and dress another child for burial, nor Sylvester lift another small coffin in his wagon and drive the familiar road to their family plot at the Salt Lake City Cemetery. It’s possible that Mary Ann received some inheritance from her late father, or perhaps their farming activities had raised enough money for the family to make a fresh start. In 1888, Sylvester purchased ten acres in the hills of Mill Creek where he could make a new home and expand their farming operations.[66] By 1892, the move to Mill Creek was official.[67]

This change of scenery marked a new phase of life for Sylvester. He was almost fifty years old when he welcomed his first grandchild in 1889.[68] In Mill Creek, the James family established themselves alongside two other Black families who also owned farms, and together they enjoyed the close association that grew from this tight-knit community.[69] For three decades, Sylvester and Mary Ann supported their family by growing and selling fruits and vegetables, as well as chickens, turkeys, and pigs. As one descendant later recalled:

They used to have all kinds of fruit orchards . . . they had chickens, and they used to have pigs and vegetables . . . they used to sell the fruit. And . . . pick currants and make jellies and jams. They grew potatoes, berries, black currants, hay, grapes, and fruit trees. [70]

Sylvester’s relationship with Mary Ann remained strained, but the two appeared to reach a kind of truce that allowed them to remain in the same household. Lucile Perkins Bankhead, a niece to Sylvester, recalled how her uncle lived alone in a distant room with a bed and a stove where he did his own cooking and was “clean as a pin.”[71]

Sylvester was no recluse, however. He especially relished time with his grandchildren, extended family, and neighbors. Granddaughter Henrietta remembered how they would pick watercress, bundle it, and ride around in his wagon selling it to neighbors. In less sober times, he would take grandchildren on wild buggy rides and trips to the candy store. These escapades delighted the children, but frightened Mary Ann. He was also a storyteller. Sylvester frequently regaled his grandchildren with pioneer stories from when he “crossed the plains.” Perhaps it was on the overland trail that Sylvester first learned to catch and cook squirrel, a specialty that both alarmed and delighted his family whenever he prepared it.[72] These eccentricities notwithstanding, his skill in farming earned him a spot as one of several delegates (including neighbors Henry and Ned Leggroan) representing Utah at a 1915 conference of the National Negro Farmers in San Francisco.[73]

The abundance of vegetable gardens and orchards meant that he would not repeat the hunger he felt as a child. Nor would Sylvester be alone. Spending time with the many children who played freely among the farms on “the hill” may have brought a kind of healing for the pain and loss Sylvester passed through as a younger man. He had worked out a co-existence with Mary Ann that despite their differences, offered him a place among family.

Sylvester likewise found a place alongside his former religion. Although he had left Mormonism behind, he held firm to his identity as Jane’s eldest son and pioneer. In celebrations commemorating the first arrival of Latter-day Saints to the Salt Lake Valley, Jane and Sylvester shared the spotlight as original “1847 Pioneers.” The two were also among a dwindling number of people who could claim to personally know the Prophet Joseph Smith. In 1904, over one-hundred 1847 Pioneers formed a procession of wagons and carriages for the parade. Among those who passed by cheering spectators was “Sylvester James, and his mother Jane Eliza James, aged 83, both colored people. Mrs. James was employed in the home of the first Joseph Smith in Nauvoo prior to 1844.”[74] Sylvester’s disaffection from the church and move to Mill Creek may have distanced his relationship with his mother, but these moments offered common ground.[75]

In 1913, Sylvester posed for a Pioneer Day photo along with his 1847 cohorts that made the cover of the Deseret News.[76] When the dwindling group of pioneers met in 1918, Pioneer Day organizers arranged for the surviving pioneers to ride in cars to various points of historic interest, “including a trip to the mouth of Emigration Canyon, where they looked back for a brief space on the road on which they traveled many years ago.”[77] We can imagine eighty-year-old Sylvester gingerly climbing out of the car to take in the view. Such a moment would likely invite a bittersweet reflection of his canyon descent seventy-one years before. With brother Silas and parents Jane and Isaac now gone, Sylvester would be the last survivor of the original family’s long journey to Zion.

For Latter-day Saint pioneers, Zion was not just a destination, but a place “of one heart and one mind,” where saints could “dwe[ll] in righteousness; and there was no poor among them.”[78] For Sylvester, this Zion would not materialize. Yet in a way, his small community in Mill Creek was the kind of place where he found a small corner of belonging. At the end of his life, he would outlive all but one of his eight children. After Sylvester died on March 5, 1920, his surviving son and grandchildren laid his coffin in a wagon and conveyed Sylvester to the cemetery.[79] His final resting place would be in Mill Creek alongside his wife and daughter, Nettie.[80] At the time of his death, he would leave seven living grandchildren. Over the next two generations, the James family line that had hung so precariously would ultimately flourish.

To these descendants, Sylvester’s legacy is a complex one. From New Canaan to Nauvoo to Salt Lake City, to Mill Creek, Sylvester’s life was a witness to Mormonism’s best and worst. Perhaps no Latter-day Saint—except his mother Jane—bore such a sustained witness to the experience of Black church membership in the nineteenth century.

By Cathy Gilmore

[1] Sources are inconsistent on Sylvester’s birth date. For this biography, I use the date of March 1, 1838, cited in Sylvester’s church membership records. Historical Department Journal History of the Church, 1830-2008, 1840-1849, 1847 January-June, p. 996, Church History Library; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Salt Lake First Ward, CR 375 8, box 2168, folder 1, image 59, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah. See also Quincy D. Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel: The Life of Jane Manning James, a Nineteenth-Century Black Mormon (Oxford University Press, 2019), 14-17, 157n21.

[2] Jane Manning James’s silence surrounding the identity of Sylvester’s father, together with Sylvester’s comparatively lighter skin and straighter hair, generated speculation among Jane’s relatives and fellow church members. Elizabeth Roundy, who dictated Jane’s autobiography decades later, added her own addendum that Isaac James (Jane’s brother) stated that Sylvester’s father was a white preacher. See Jane Manning James, “Jane Manning James Autobiography” (Salt Lake City, Utah, ca 1902) MS 4425, Church History Library, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, Appendix, 149. Sylvester himself claimed he was the son of a French-Canadian man. See Florence Lawrence Henrietta Leggroan Bankhead interview, transcript, November 22, 1977, 9, 24, Helen Zeese Papanikolas Papers, box 2, folder 3, Marriott Library Special Collections, University of Utah.

[3] In 1840, Sylvester was enumerated in the household of Jane’s mother Philes (sometimes referred to as Eliza) and stepfather Cato Treadwell. Jane’s sisters Angeline and Sarah, and brothers Isaac Lewis and Peter also lived there. See United States, 1840 Census, Connecticut, Fairfield County, Town of Wilton.

[4] James, “Autobiography,” 1.

[5] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 25.

[6] For a list of probable members of the group who travelled to Illinois, see Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 26-27 and W. Paul Reeve, “‘I Dug the Graves’: Isaac Lewis Manning, Joseph Smith, and Racial Connections in Two Latter Day Saint Traditions,” Journal of Mormon History 47, no. 1 (January 2021): 36.

[7] James, “Autobiography,” 1-2; Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 33-34. Jane Manning was born free and therefore did not possess the “free papers” that Peoria, Illinois officials demanded to see. Newell suggests that Jane and her family may not have realized that “certificates of freedom” would be required of all Blacks traveling through certain states.

[8] James, “Autobiography,” 2.

[9] James, “Autobiography,” 2.

[10] Stephen C. Taysom, Like a Fiery Meteor: The Life of Joseph F. Smith (University of Utah Press, 2023), 48. Taysom suggests that The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints possessed a certain “religious portability” that made it particularly adaptable to the changing environments of displaced church members.

[11] “Was Cook for Prophet Joseph; Negro at Pioneer Day Fete,” Salt Lake Herald Republican, July 26, 1910, 10. Cited in W. Paul Reeve, “‘I Dug the Graves’: Isaac Lewis Manning, Joseph Smith, and Racial Connections in Two Latter-day Saint Traditions,” Journal of Mormon History 47 no. 1 (2021): 40.

[12] James, “Autobiography,” 3.

[13] James, “Autobiography,” 2.

[14] The boyhood memories Jesse N. Smith of his cousin, Joseph Smith, Jr., revealed what impressions the church’s prophet made on the young boy: “I have never heard any human voice, not even my mother's, that was so attractive to me…. I was comparatively a poor and friendless child… I felt somewhat forlorn, for we were in poverty… What wonder then that I feel justified in saying that [Joseph] was my friend. What wonder that he was almost deified in my mind.” Jesse N. Smith, The Journal of Jesse N. Smith: Six Decades in the Early West, ed. Oliver R. Smith (Utah: Jesse N. Smith Family Association), 454-455.

[15] Reeve, “I Dug the Graves,” 40.

[16] The Jameses retained a persistent association with the Prophet Joseph Smith’s family throughout their lifetime. Jane Manning James’s “Autobiography” devoted an outsized portion to her time with the Smith family.

[17] James, “Autobiography,” Appendix, 147.

[18] Reeve, “I Dug the Graves,” 40.

[19] Sylvester’s appearance in subsequent membership records of baptized church members indicates that Sylvester had been baptized. Other records such as his 1861 membership in the Nauvoo Legion Militia in Utah and 1885 excommunication also point to Sylvester as a being a baptized member of the church. A search of probable sources from Winter Quarters and the Eighteenth Ward where the James family lived after arriving in the Salt Lake Valley do not contain a baptismal date for Sylvester. See Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Salt Lake First Ward, CR 375 8, box 2168, folder 1, image 59, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah; L. Fullmer, “Report of the 1st Regt., 2nd Brig. J.L. Commanded by A. L. Fullmer, Dec. 27, 1861,” December 27, 1861, image 12, Utah, Territorial Militia Records, 1849-1877, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[20] “Daniel Spencer’s 100, Schedules, circa 1847 February,” February 1847, MS 14290, box 1, folder 16, image 13, Camp of Israel schedules and resorts 1845-1849, Church History Library; Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 65-66.

[21] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 65.

[22] Joseph F. Smith and Jesse N. Smith were roughly the same age as Sylvester when they emigrated to the Great Basin. Their memories of the trail include working as a “herd boy” driving cattle, driving oxen, and encounters with Native Americans. See Taysom, Like a Fiery Meteor, 50-53; Smith, The Journal of Jesse N. Smith, 11-12.

[23] “Salt Lake Observes Day of Pioneers, Notable Old Settlers,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 26, 1904, 2; “Utah Celebrates her Sixty-Sixth Birthday,” Deseret News, 24 July 1913, 1; “Pioneers in Parade,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 25, 1913, 14.

[24] Utah, U.S., Mormon Pioneer Overland Travel Records, 1847-1868.

[25] “A List of President Brigham Young’s Family Residing in the 18th Ward,” March 19, 1855, Brigham Young office files; Miscellaneous Files, 1832-1878. The James family are enumerated separately under the title of “Help.”

[26] Children who lived in the Salt Lake Valley during this time frequently recalled feeling hunger. Jesse N. Smith, who entered the Salt Lake Valley a few days after Sylvester, recalled his hunger at the time: “I was just at an age when my appetite was very keen, but there was no help for it… I was exceedingly hungry, for months my hunger for food was not satisfied.” Smith, The Journal of Jesse N. Smith, 13, 176.

[27] For a breakdown of Black populations listed in the 1850 United States Federal Census, see Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 79-80.

[28] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 76. Newell describes how both Jane and Isaac had to assert their status as free individuals, especially during the 1850s when “Southern converts were arriving in the Salt Lake Valley with large numbers of slaves.”

[29] W. Paul Reeve, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (Oxford University Press, 2015), 118-128. Latter-day Saint positions on abolition and race mixing were often subject to the political expediency of the moment. While several Black men had received ordination to the Latter-day Saint priesthood prior to 1847, others were denied access to priesthood offices.

[30] For a discussion on the various justifications and reasonings behind Brigham Young’s racial policies in relation to Indian and Black servitude, abolition, race-mixing, and religious exclusions, see Reeve, Religion of a Different Color, 148-161 and W. Paul Reeve, Christopher B. Rich Jr., and LaJean Purcell Carruth, This Abominable Slavery: Race, Religion, and the Battle over Human Bondage in Antebellum Utah (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024).

[31] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 74-75; Brigham Young, February 5, 1852, CR 100 912, Church History Department Pitman Shorthand transcriptions, 2013-2021, Addresses and sermons, 1851-1874, Miscellaneous transcriptions, 1869, 1872, 1889, 1848, 1851-1854, 1859-1863, Utah Territorial Legislature, 1852 January-February, CHL. While Latter-day Saints taught the doctrine of eternal families, Black church members were denied access to the temple rites that would “seal” their family members together. Sylvester’s mother Jane would take up this cause. For the last three decades of her life, Jane petitioned church leaders for access to temple rites that would afford her the same blessings as white Latter-day Saints.

[32] Reeve, Rich, and Carruth, This Abominable Slavery. For the various speeches from the legislative session which document the racism see www.ThisAbominableSlavery.org.

[33] Jesse C. Little, “Tax Assessment Rolls” (Salt Lake City (Utah) Assessor, 1856), Series 4922, box 1, folder 1, Utah State Archives.

[34] Although no battles marred the Utah landscape, Latter-day Saints temporarily abandoned Salt Lake City to avoid clashes with incoming federal troops determined to remove Brigham Young as territorial governor. The April-to-July displacement disrupted agricultural operations for farmers like the Jameses.

[35] A.L. Fullmer, “Report of the 1st Regt., 2nd Brig. J.L. Commanded by A. L. Fullmer, Dec. 27, 1861,” December 27, 1861, image 12, Utah, Territorial Militia Records, 1849-1877, Family History Library, Salt Lake City.

[36] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 84.

[37] United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, Ward 8.

[38] For information on the family of Mary Ann Perkins, see Amy Tanner Thiriot, Slavery in Zion: A Documentary and Genealogical History of Black Lives and Black Servitude in Utah (The University of Utah Press, 2022), 249-262.

[39] Salt Lake City, Utah, City Directory, 1867, 66, Ancestry.com. This directory shows Isaac James living on 700 East between 800 and 900 South, and Sylvester James living on 800 South between 800 and 900 East.

[40] United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, Ward 1.

[41] Elias Smith, Jane E. James v. Isaac James (Salt Lake County Probate Court March 1870); Jane and her children Silas, Jessie, and Vilate moved from the Eighteenth Ward to the Eighth Ward. Jane joined the Eighth Ward Relief Society on November 1, 1870. “Eighth Ward Relief Society Minutes and Records (1867-1969),” LR 2525 14, LDS Church History Library.

[42] United States, 1870 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Salt Lake City, Ward 7. Miriam likely married Joseph Williams some time in 1868 at age seventeen or eighteen.

[43] 1870 United States Federal Census, Utah Territory, Box Elder County, Corrine City, Household 96; MaryAnn gave the surname “Robinson” to the enumerator although it is unclear if a marriage had taken place. Towns like Corrine symbolized this change with the promise of free commerce, a railroad hub, and amusement free from Mormon influence. For more on the forces that shaped these tensions, see: David Walker, Railroading Religion: Mormons, Tourists, and the Corporate Spirit of the West (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press: 2019).

[44] Ellen Madora had daughter Melvina on August 10, 1869—one month before her sixteenth birthday.

[45] U.S. Federal Census Mortality Schedules, 1850–1885, Box Elder, Utah Territory, 1870. MaryAnn’s newborn, Joseph, died just one month before census workers knocked on her door.

[46] “Utah, Salt Lake County Death Records, 1849–1949,” FamilySearch; Entry for Mary Ann Robinson and Isaac, 09 Apr 1871; “Utah, Salt Lake, Salt Lake City, Cemetery Records, 1847–1976,” FamilySearch, Entry for Marie Ann Robinson and Isaac James, 1871.

[47] “Utah, Salt Lake, Salt Lake City, Cemetery Records, 1847–1976,” FamilySearch, Entry for Henry Robinson and Mary Ann, 1871.

[48] Death records for Nellie James show conflicting years of birth, but her ecclesiastical blessing record from September 1, 1871, indicates her birth date as April 28, 1871. Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Salt Lake First Ward, CR 375 8, box 2168, folder 1, image 59, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[49] Cathy Gilmore, “Silas F. James,” Century of Black Mormons.

[50] Salt Lake County Land Title Certificates, Sylvester James, 1871–1872, Box 18, Folder 63; Salt Lake County Land Title Certificates, Jane E. James, 1871–1872, Box 18, Folder 61. Sylvester’s folder contains three documents: an application dated December 11, 1871, a Probate Court Notice dated June 28, 1872, and a Certificate of Land Title dated July 1, 1872. Notably, the Application shows Silas James as the original applicant, but Silas’s name is crossed out and Sylvester is written in. It is unclear if Silas’s illness played a role in this change, but it is likely that his tuberculosis prevented him from heavy farming labor, perhaps justifying its acquisition by Sylvester. Jane’s probate appearance was likely connected to her deeding a part of her property to her daughter Miriam (see Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 96).

[51] “Local and Other Matters,” The Deseret News, 19 May 1874, 12.

[52] Nettie James was born October 12, 1873, and died June 19, 1874. “Utah, Salt Lake, Salt Lake City, Cemetery Records, 1847–1976,” FamilySearch.

[53] Sylvester James, Jr., was born January 2, 1874, and died on June 29, 1874. “Utah, Salt Lake, Salt Lake City, Cemetery Records, 1847–1976,” FamilySearch.

[54] “Utah, Deaths and Burials, 1888–1946,” FamilySearch, Mariam Williams, 1874.

[55] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 97–100.

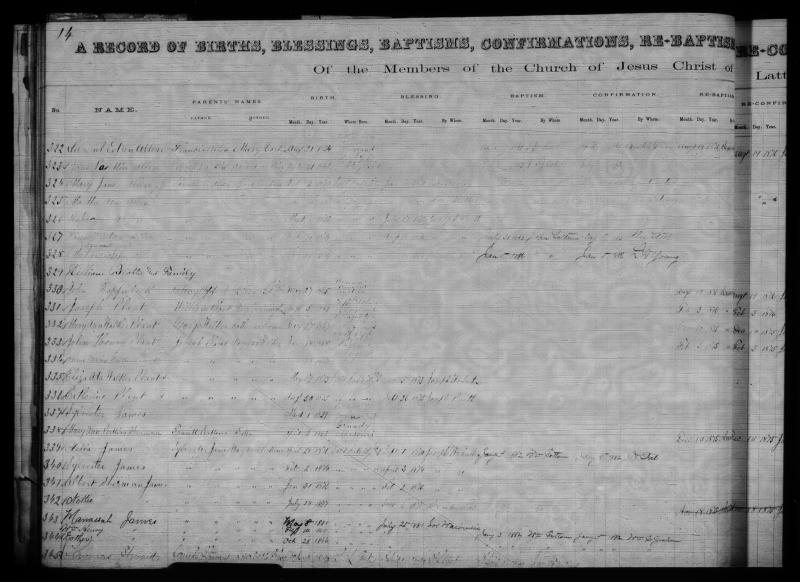

[56] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Salt Lake First Ward, CR 375 8, box 2168, folder 1, image 59, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[57] In the nineteenth century, the prohibition of consuming alcohol outlined in the Latter-day Saint Word of Wisdom was unevenly enforced. See Paul H. Peterson and Ronald W. Walker, “Brigham Young’s Word of Wisdom Legacy,” BYU Studies 42, nos. 3 & 4 (2018), 29–64.

[58] Henrietta Leggroan Bankhead, interview by Florence Lawrence, 1977, 21, Papanikolas Papers, 6, 16. In Tonya Reiter, “Life on the Hill: The Black Farming Families of Mill Creek,” Journal of Mormon History 44 no. 4 (October 2016), 68–89.

[59] Mary Lucile Perkins Bankhead, Oral History, interview by Alan Cherry, Salt Lake City, Utah, 1985, 9, Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, LDS Afro-American Oral History Project, 1985–1987, MS 10176, Church History Library, 10. In Reiter, “Life on the Hill,” 86.

[60] When asked about Sylvester’s disaffection, Lucile Bankhead said, “when he first came here he kept on with the Ox team to San Bardino California for the Mormon church and I don't know what they done to him on the way either going or coming or something but he quit the Mormon church.” Mary Lucile Bankhead, interview, 10.

[61] “[Jane] didn't have no husband when she come… she didn't have a husband she came but she had these children. I don't know where she got them but she had them and they were so different […] everyone that saw them commented on them and being different...” Celia and Carrie Bankhead Leggroan, interview by Ronald Coleman, 1977, 7, Helen Zeese Papanikolas Papers, 1954–2001.

[62] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 107; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Salt Lake First Ward, CR 375 8, box 2168, folder 1, image 59–60, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[63] Newell, Your Sister in the Gospel, 109. Ellen, who also went by the name of “Nellie Kidd,” had worked in houses of ill repute in Nevada and San Francisco before returning to Salt Lake in 1886.

[64] A local paper noted that Sylvester “appeared with a bandage around his head, indicating that that portion of his anatomy had been undergoing some unusual process that rendered it unpleasant and unsightly.” See “Handcuff Hankerings,” Salt Lake Evening Democrat, January 11, 1887; “A Brutal Assault,” The Salt Lake Herald, January 12, 1887, 8.

[65] Extant city directories from 1867 to 1888 list Sylvester James at this address. See U.S., City Directories, 1822–1995, 1867, Ancestry.com, Lehi, UT, USA.

[66] Salt Lake County Recorder, Abstract Book B-3, page 259, line 1.

[67] The exact date of their relocation to Mill Creek is unknown, but an 1890 city directory that lists Sylvester as both a resident of Salt Lake and Mill Creek suggests that the move took several years to finalize—at least until 1892. Church records indicate the family was received into their new ward in 1893. See Salt Lake City, Utah, City Directory, 1889, 1890, 1892, Ancestry.com; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, South Cottonwood Ward, CR 375 8, box 6522, folder 1, image 32, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah; Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Record of Members Collection, Mill Creek Ward, microfilm 26,147, Family History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[68] United States, 1900 Census, Utah Territory, Salt Lake County, Mill Creek Precinct. Hyrum Leggroan was born May 3, 1889. He was the son of Esther James and Henry Leggroan.

[69] Reiter, “Life on the Hill,” 72–73. Former neighbors Samuel and Amanda Chambers and Ned and Susan Leggroan had farmed in Mill Creek since the 1870s.

[70] Henrietta Bankhead, interview, 7; Florence [Leggroan] Lawrence Oral History, “Interviews with Blacks in Utah, 1982–1988,” 94, 134, MS 0453, box 5, folders 7–8, Marriott Library. In Reiter, “Life on the Hill,” 78.

[71] Henrietta Bankhead, interview, 9; Reiter, “Life on the Hill,” 77.

[72] Mary Lucile Bankhead, interview, 5; Henrietta Bankhead, interview, 16. In Reiter, “Life on the Hill,” 77–78.

[73] “Judge Loofbourow Appoints Delegates,” The Salt Lake Tribune (Salt Lake City, Utah), 31 Jul 1915.

[74] “Salt Lake Observes Day of Pioneers, Notable Old Settlers,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 26, 1904, 2.

[75] The common ground Sylvester found with his mother Jane and wife Mary Ann proved more difficult with his sister. Following Jane’s passing in 1908, Sylvester filed a lawsuit against his sister alleging that she had used “undue means of persuasion” in convincing their mother to deed her property to Ellen. The judge would eventually rule in Sylvester’s favor. See “Used Undue Influence,” Deseret News, 20 May 1909, 2; “Old Woman’s Deed Set Aside by Court,” Deseret News, 21 May 1909, 12; “Judge Morse Sets Aside Pretended Conveyance,” Salt Lake Tribune, 21 May 1909, 14.

[76] “Utah Celebrates her Sixty-Sixth Birthday,” Deseret News, 24 July 1913, 1; “Pioneers in Parade,” Salt Lake Tribune, July 25, 1913, 14.

[77] “Impressive Tribute Paid to Pioneers of Beehive State,” Deseret News, July 24, 1918, 9.

[78] Pearl of Great Price, Moses, 7:18.

[79] Utah, U.S., Death and Military Death Certificates, 1904–1961, Utah Deaths, 1900–1951, Iron County – Salt Lake County, 1920.

[80] U.S., Cemetery Index from Selected States, 1847–2010.

Documents

Click the index tab in the viewer above to view all primary source documents available for this person.