Research

Higher Education and Academia

Research is an integral part of higher education. In recent years, there has been a greater focus on achieving excellence in research. More specifically, an increased expectation for an accelerated research pace. There are psychosocial consequences of these organizational changes for everyone. However major issues can arises because of researchers' gender ("Accelerated Researchers").

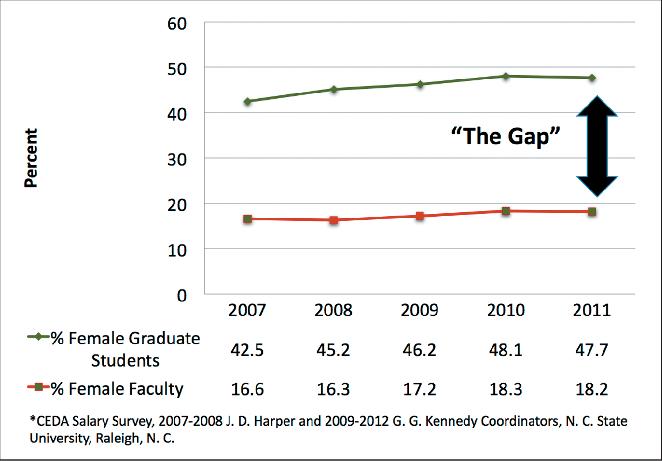

A researcher's gender affects the distribution of responsibilities. Because of biases present within an academic structure. For example, many female researchers have cited instances of being mistaken as assistants rather than principal investigators. Women can have their opinions or findings ignored. They can receive less space for their research endeavors. As well as many other experiences ("Picture a Scientist" documentary). These experiences show that there is a gendered construction of scientific excellence and that people work to maintain that status quo. These discriminatory practices and harassment affect how many women choose to continue pursuing higher education and research ("Accelerated Researchers").

The established pattern for research is a hegemonic male working model. Valuing stereotypically masculine personality traits. With complete dedication to work. Regardless of outside commitments. The meritocratic nature of research also leads to uncertainty and hypercompetition. Due to a lack of permanent positions, as well as increased feelings of self-doubt when individuals are not able to continue research. Especially while maintaining other areas of their lives. Eventually, researchers may develop more individual-focused strategies to continue their research. They may start straining interpersonal relationships, limiting collaboration, and devaluing personal, ethical, and moral values ("Accelerated Researchers").

This hegemonic male working model can also foster an environment where female researchers are not respected in the same way as their male counterparts. Since women do not fit into the "model" of a researcher. Fellow researchers may be able to make inappropriate comments without repercussions. Additionally, women may not feel comfortable bringing up experiences of harassment or disrespect because it is so normalized within the research field.

In terms of universities and research institutions, there has been a focus on quantity of research rather than quality. As well as a focus on the significant results rather than null. The former deprioritizes the lives of part-time researchers and people with more extracurricular responsibilities. The latter focus has had major influence on research as a whole. As it leads to more unethical practices, such as fabricating result. This can com from a need to publish significant results.

Lisa Diamond, PhD discussed an element of academia in which diversity is not really allowed, namely how people pursue higher education and research endeavors.

"I think that the university systems are not very good at finding ways to reward scholarship that may look a little different from what they're used to, or that may have a different sort of trajectory. Scholarship that takes longer, or that's more community-engaged, or that doesn't yield the same number of publications. It's like there's a certain model of what success looks like at the university, and as much as people like to talk about being inclusive and representing diverse forms of scholarship, when it comes down to it, when people produce knowledge that doesn't fit the mold that they're used to, it's really hard to get that work acknowledged and validated." -Lisa Diamond, PhD

S. Mckenzie Skiles details how she did not feel comfortable bringing up disrespectful comments made by her male counterparts when she was participating in research in graduate school.

"Men would just say really sort of dismissive and rude or even offensive things and I would just pretend to ignore it, or not hear it, or pretend not to be offended, or I just would never say anything because I didn't want to rock the boat or be difficult. Especially when I had to kind of force my way into getting those experiences in the first place, I was just always afraid of people being like…"why did she end up coming? She's difficult. We're not going to invite women anymore," or something like that. I think I probably should have spoken up sooner because now that I'm more established, I'm not afraid to say something but when you’re in graduate school and you're new to everything, it can be really intimidating to bring it up."

Amy Sibul, MS described her "unconventional" approach to completing research for her masters degree, in which she wanted to pursue a research topic that was not widely focused on, but she found a way.

"So I hopped in my car. I put my mountain bike on my little tiny used crappy Honda Accord and I drove to Utah and made an appointment with him and I don't think that's normally how things are done. It was informal and funny and I think it shocked James McMahon into accepting me into his graduate program because it was like, 'Hey, I really want to be a student in your lab, this is what I want to study.' And he said, 'Okay, but you have to find your own money.' So I did. I wrote a grant proposal to a petroleum company, and they gave me $15,000 and they funded my master's degree." -Amy Sibul, MS

Lisa Diamond, PhD discussed one element affecting women's presence in scientific fields, which is the expectation (i.e. assumption) that women will eventually leave their careers to pursue more family-related endeavors.

"If you were a woman who was going to have a baby, it's just like, “Well maybe you're not the go-getter that we thought you were. ...I think it's probably safe to imagine that in the harder sciences, which tend to be a little more patriarchal, that [childcare] is even a stronger expectation, you know? And then in things like business, you know. I think psychology as a profession has a lot more women in it, than in like the hard sciences. And so I think that makes it a little easier, so I think a lot of it has to do with whether it's a profession that has a lot of women in it to begin with." -Lisa Diamond, PhD

Collaboration

Collaboration in scientific research is critical. Collaborating can advance one's career, make one's work more visible, as well as produce unique results because of the influence of diverse perspectives. Women in scientific fields have long been excluded from the networking activities in science due to both implicit and explicit biases. Evidence suggests that biases that favor male scientists, as well as lack of self-esteem and sexual harassment, may all play a role in preventing women from advancing in their fields. Furthermore, there are institutional differences that favor men, such as conferences that only invite men or only have male speakers.

In her interview, Cynthia Burrows, PhD describes the necessity of collaborating within research.

"Actually it's important to have a team. I think it's really hard to do research on your own in a vacuum, you know? If somebody just gave me all the toys and all the chemicals I would need, put me in a room, I could stay busy for awhile, but if I didn't have people to talk to about what's important, about other ways to do things, then I don't think I would thrive in that environment. So research is very collaborative." -Cynthia Burrows, PhD

Kristina Feldman, PhD notes how important it is for women to collaborate as this gives women the opportunity to advocate for themselves in academic spaces.

"I think as a woman, we're not necessarily taught to ask for what we want. I think having that supportive environment was really, really helpful because we just continued to lift each other up and support each other and made an environment where we could ask for things." -Kristina Feldman, PhD

Holly Sebahar, PhD concludes that collaboration with peers can serve as inspiration in the face of neutral or ambivalent advisors and professors.

"When I had professors that I didn't feel particularly supported by. I really tried to work with my peers. So I had a lot of friends in my classes, or I would try to make friends. We would get through the class together. That was generally my experience." -Holly Sebahar, PhD

Aside from collaborating with other academics or scientists. There is also collaboration with the community (e.g. nonprofit organizations) to gain knowledge and apply research findings to real-world situations. Amy Sibul, MS notes that she is closely involved with this aspect of collaboration in her work, and describes building community relationships as a necessary experience in college.

"Scholarship and academia is an incredibly important, valuable way to gain knowledge. However, gaining knowledge through applied work with agencies and nonprofits and in all communities is also incredibly valuable. The field I'm in, conservation biology, is nothing without community involvement. ...I tend to feel like building relationships with community is just the whole point of higher education. Students are going to get their degrees and graduate and then they're going to go do something. They're going to be part of a community." -Amy Sibul, MS

Scientific Objectivity

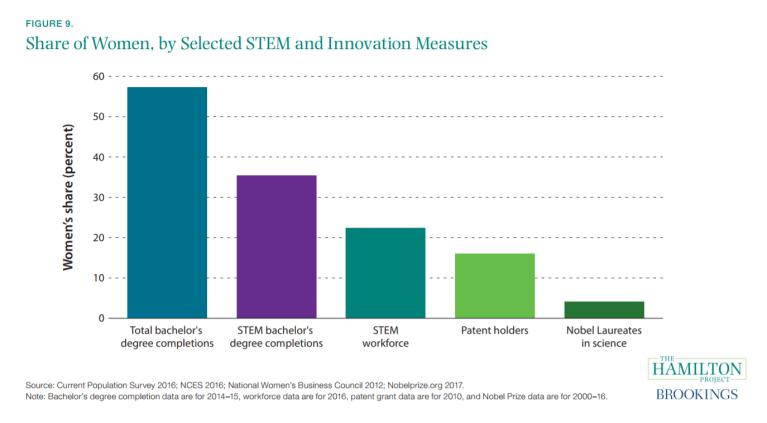

Science has long been thought of as being entirely rational and objective. Traits traditionally associated with masculinity, just as science itself has been (Dajani). Science has always shown a level of inequality between the sexes, demonstrated by the historical and present-day lack of women involved, as well as the lack of research completed involving the female experience of the world ("Feminist Perspectives on Science").

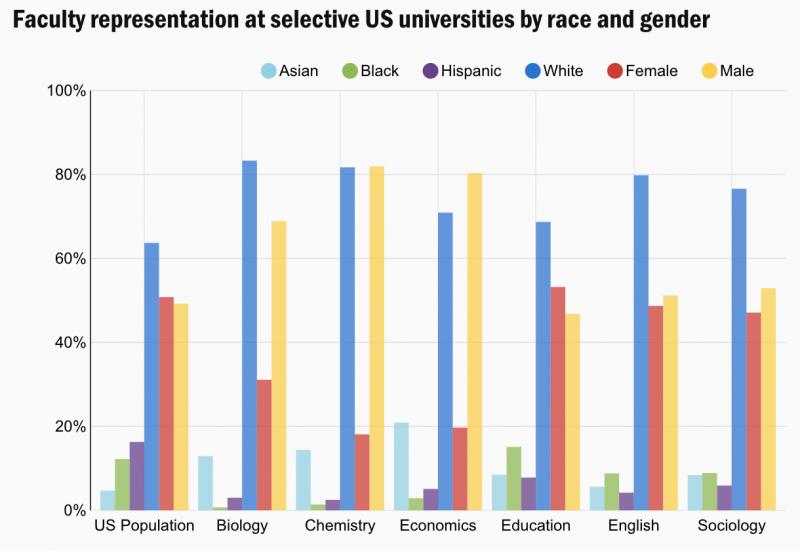

A focus on separation between researcher and research subject/participant has led to women feeling a lack of belonging within science. Since objectivity has been "identified as a male way of interacting with the world" (A Feminist Critique of Scientific Objectivity). Methods of scientific inquiry that are more aligned with how women interact with the world are viewed as less legitimate, "softer" sciences (e.g. psychology, anthropology, sociology, etc.) and are at the bottom of the hierarchy of the sciences (A Feminist Critique of Scientific Objectivity).

Lisa Diamond, PhD notes her experiences with objectivity in science multiple times in her interview, but most notable was how she described connecting with her participants in a narrative study on sexual fluidity of women.

"I was committed ethically to breaking down that false line of objectivity...and really connecting with participants, on a personal level. Which is like exactly what you're not supposed to do, as a scientist." -Lisa Diamond, PhD

Amy Sibul, MS similarly notes that she wanted to combine her passion for natural science with a more human element.

"I had this opportunity to interact with professional biologists on the Galapagos Island who were really engaged with the science of, you know, nature and biological questions, but they were also engaged, at the same time, with outreach and education to the public. To me that was the clincher. I knew I wasn't perfectly suited to basic research being isolated from humans, I wanted to have that human component and I wanted to figure out how to mix the two, and seeing those kinds of biologists in action on the Galapagos Islands is what gave me a path forward like, oh okay, well, I really can incorporate the human component into my passion for the natural world into a career." -Amy Sibul, MS

These anecdotal experiences from interviewees suggests that women who are involved in science tend to gravitate towards fields and sub-fields that involve connecting with people more than the "hard sciences" have historically done. This is supported by evidence showing that women often pursue career paths that align more closely with their goals and values (e.g. having a family, helping others, involving social justice, etc.). One research study reviewed a physics subfield called Physics Education Research (PER) that showed a much higher level of gender parity than other subfields within physics. The researchers concluded that physicists participating in PER described a more welcoming climate for both genders, and had more personally meaningful goals, such as producing a stronger scientific workforce for the future.

Diverted attention is a large problem for women in STEM. Often, male researchers will choose to extend their attention to male students, which leaves female researchers abandoned and without a stable source of support. A lack of higher support can often be detrimental for female researchers and sometimes results in their dropping out.

"Yes, yes. I feel like I always had to work, maybe not twice as hard, but always had to work harder than male graduate students who are at the same level as me. I had to present better and publish more and still didn't feel like I got as much credit as male colleagues sort of at the same level or similar career stage as me. And honestly, that still happens. That's something that has not changed over time, which is really unfortunate, but it's a little sad to say this, you just get used to it, men getting more recognition than women in the field." -S. Mckenzie Skiles, PhD

Skiles illustrates two very important points within her anecdote. She first expresses the fact that women will need to work harder than their male counterparts to achieve success. Secondly, she expresses that women within STEM will need to accept the attention male students will be given over female students.

Page written and researched by Kaylee Martin. Edited by Lily Jones and Simon Lee.

Later edited by Pamalatera C. Fenn